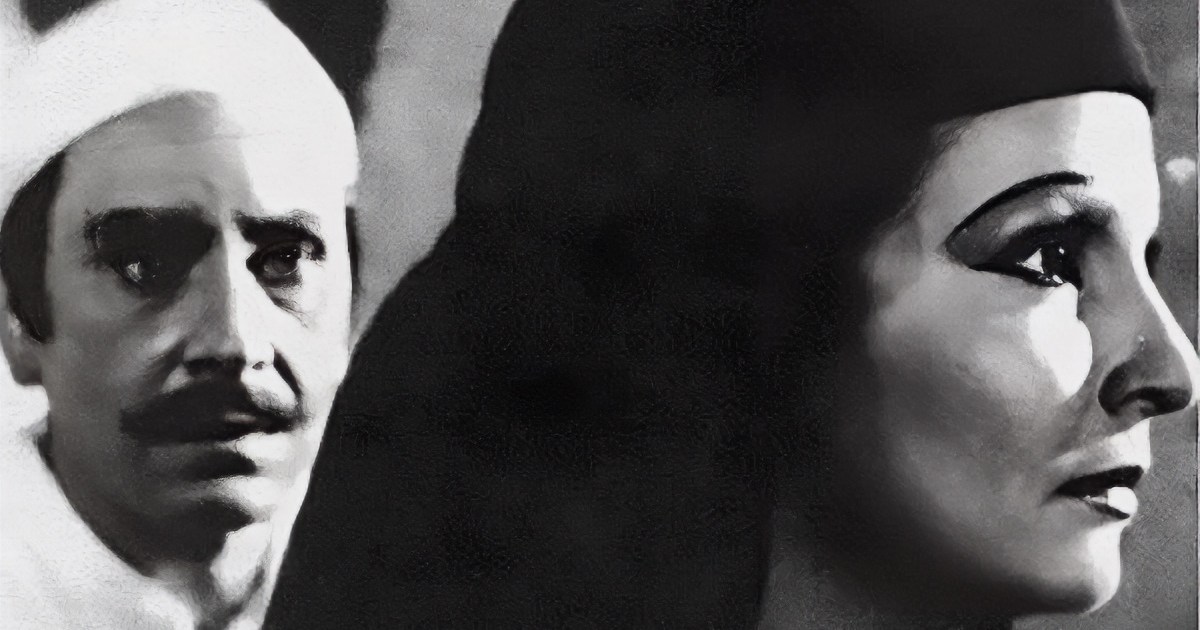

From the movie Something of Fear (Social Media)

Egyptian cinema was not devoid of the religious dimension in general in many of its films, nor was it devoid of one of the most important manifestations of religious discourse, which is: the fatwa. We have seen several cinematic films in which the fatwa appears as one of the components of the dramatic or cinematic work, especially the stage that relied on novels. Literary works or films written by people with a long history in Arabic and Egyptian literature.

The position of the fatwa and muftis on cinema and art in general has often been discussed, and this is what writers and researchers focus on. However, another area has not received research or written attention, which is the area: the fatwa on cinematic films, the contexts in which the fatwa is received, and the extent of its validity from a jurisprudential standpoint. Did her dramatic use pay off, or not?

Why was the fatwa present in many films before, while it completely disappeared a while ago?

I do not know of a book or writer that has dealt with the subject in an investigative, research manner, except for what was recently mentioned in a chapter of a book issued by the Egyptian Fatwa House, within the Encyclopedia: The Egyptian Teacher of Fatwa Sciences, in its sixteenth part, which dealt with the topic: Fatwa and Social Sciences, in its seventh chapter. Titled: Fatwa and Art.

He dealt with some of the films that were subject to the fatwa, without limiting it, or fully examining it. It is an important effort that fits the space required for research. Its focus was more on the impact of the fatwa and its relationship to the arts in general, but it is an effort that is considered a beginning to build on, but it is not sufficient in the matter.

Anyone who contemplates Egyptian cinema and its films, in terms of their relationship to fatwas and fatwas, will find that there are some Egyptian films that made one of the fatwas the backbone of their dramatic line, but without focusing on that the matter is related to the fatwa, and that there are other films in which the fatwa was a dramatic thread in the end, so that it ends The film, or the dramatic plot, is based on a fatwa, whether its transmission is correct or not, and whether this fatwa is likely or likely, strong or weak.

This is if we exclude the comedic form in which the fatwa appears in some films, such as the movie (Hassan and Morcos), for example, where a Christian priest was forced to disguise himself as a Muslim sheikh for security reasons, and he went to an area different from his previous area of residence, and when they learned of his presence as a sheikh, they asked him to the mosque, in the presence of... Another sheikh, and they pressed him with questions and fatwas, and whenever he was asked about a fatwa, he said: “What does religion say?”

The real Muslim Sheikh next to him answered, and so on until it became a necessary phrase when discussing and dialogue about a matter that seemed to contain religious humor.

Films starring a fatwa

Among the films in which the fatwa was the backbone of the dramatic structure are two films:

The first: (Something of Fear), which tells about the village of (Al-Dahashna), which is ruled by a murderous, plundering and plundering person, namely (Atris), who loved a girl from his youth (his heart), and because she stood up against his injustices, by opening (the lock) for people to drink and be given water. He planted them, asked her for marriage but she refused, so the father lied to make Atris believe that she agreed.

One of the village elders learned about this.

Sheikh Ibrahim, to keep moving among the people, with the famous sentence in the movie: “The marriage of (Atris) from (his heart) is invalid.” The marriage is invalid, until (Atris) killed his son, so the people came out carrying the son’s body, shouting behind the sheikh with the fatwa: “The marriage of Atris from "His heart is false."

I wrote on the walls.

It is known that the film caused a stir at the time, and was almost banned from being shown, and that what is meant by “Atris” here is “Abdel Nasser” and “Dahashna” are the Egyptian people who will revolt one day, and it is known historically that family or personal status issues were used to expose political affairs. Like Imam Malik’s fatwa regarding divorce under duress, and the people understood from that that he meant the pledge of allegiance to the ruler, which was taken from them under duress.

As for the second film, a false fatwa became famous, at the expense of the correct fatwa, which many did not pay attention to. It is the film: (The Second Wife), in which the village mayor who did not have children;

Because his wife is barren, so he forced a farmer to divorce his wife so that he could marry her and have children with her, and attribute the child to him and the first wife. When the mayor forced him, the sheikh of the country used to say to him: “And obey God, and obey the Messenger, and those in authority among you,” as a fatwa regarding obedience to the ruler, and it became famous as a refrain in Egyptian history. Hadith, whenever people want to make fun of a mufti, they say: He is like so-and-so in the movie, and they repeat his same phrase.

People did not pay attention to the most important and dangerous fatwa in the film, which is the correct fatwa, based on which the peasant girl - who was forcibly divorced from her husband - established her plan to take revenge on the unjust mayor. She went to Al-Hussein Mosque for a visit, and one of the sheikhs saw her crying, and when she narrated the situation to him, he said to her: This is an invalid divorce, and you are still your husband's wife.

Based on this fatwa, the woman became pregnant from her husband who was forced to divorce, and gave birth, which led to the death of the mayor in grief and paralysis, and the end of his injustice, and her attempt to establish justice by restoring the rights of the oppressed people in the village.

The focus was not placed on this fatwa that the woman relied on in the film, while people paid attention to a fatwa that did not come from its people. The sheikh of the country in the past was an administrative position, not a religious one, while the one who issued her fatwa in the Imam Hussein Mosque was a jurist, and he guided her to the ruling of the correct religion, so in this The film was based dramatically on this fatwa.

Films sealed with a fatwa

Among the films whose dramatic conclusion was based on a fatwa, whether it was a correct or likely statement, there are several films that we see that were based on a famous statement, which represents a jurisprudential opinion from the four schools of thought, not the majority, or the most likely opinion based on the strength of the evidence, including: the fatwa prohibiting the woman with whom the father committed adultery. On the son, or whoever commits adultery with the mother and her daughter is forbidden to him, and this is a statement according to the Hanafi school of thought.

Screenwriters before that had the ability to relate to issues of social and religious reality, contrary to what surfaced on the surface of artistic works several years ago, so most films became immersed in talking about crime and drugs.

Because the Egyptian personal status law is Hanafi, this fatwa became famous in Egyptian cinema, and was mentioned in more than one artistic work. We saw it in the movie: (Men Without Faces), where the father wanted to prevent the son from marrying a night girl who repented and loved him, and when he wanted to turn him away from the marriage He told him, untrue, that he was one of those who committed adultery with her, then after a while he confessed the truth to him.

And also recently in the movie: (Farhan Adam’s Lieutenant), it concludes at the end by not marrying the hero to the heroine because he committed adultery with the mother.

As well as the films that dealt with the issue of (the house of obedience), which is the obligation of the wife to the husband’s house, in which there is clear humiliation on the part of the man, and the husband is subjected to military action and a court ruling, in humiliating behavior that is not befitting of the family and its status in Islam, and this is what a number of people denounced. Of the scholars, and they called for it to be changed, and the House of Obedience was a fatwa issued from a jurisprudential opinion in its context and time.

There were films that sometimes concluded their final shots in the film with a fatwa, leaving the answer and solution to scholars and the law, such as the film: (The Threshold of Women), and the summary of its story: A police officer does not have children, and he keeps deluding his wife that she is the reason, even though she has received a high degree of education, and her father is a court advisor. Under social pressure, she went to quacks, many of whom resort to placing sperm on a piece of wool, and when the woman is under anesthesia, she is fertilized by it.

Indeed, the woman became pregnant, and when she told her husband to be happy about the news, he shocked her that he had no children, and accused her of adultery and forbidden pregnancy. After searching, they learned the truth, and in the last footage of the film, the court advisor, the wife’s father (the artist Ahmed Mazhar), spoke that this pregnancy is legally called: an incestuous pregnancy. So the wife asked to have him aborted, and he said to her: It is forbidden and it is not permissible to abort the fetus. She said: If she gives birth to him, and the husband refuses to acknowledge him, to whom should he be attributed?

He said: It is attributed to his mother, so the movie ends with the woman screaming: What should I do? She says it three times.

I do not know why the writer of the film chose this jurisprudential opinion, and whether he returned to a jurisprudential point of view, or whether he built this conclusion based on his personal religious culture. Its writer is Professor Mahmoud Abu Zaid, and the religious line is observed in most of his films. Some of his films end with a recited verse that expresses the position, as in the film (Shame) and he also wrote it, but the jurisprudential opinion on which he relied in the movie (Threshold of Statues) may have been broader than the position he adopted, and perhaps the conclusion of the movie was like this, intended to open the door to discussion in such cases.

Reasons for absence

This is a general look at the fatwa in Egyptian cinema, in some of its manifestations, and anyone who observes the state of cinema for several years will not find a trace of such a presence, whether for the fatwa, or for an important area of religion. Rather, we may have found the use of religious terms in the wrong place, and even in what is not permissible to use, As in the title of the movie: (Legitimate Betrayal), betrayal is not permitted under any circumstances.

Perhaps one of the most important reasons for this absence is that cinema previously relied on novels written by great writers, those with pens of literary weight and penetrating the study of reality, from which religion and fatwas are inseparable, as in the novels of Naguib Mahfouz, Ihsan Abdul Quddus, Youssef Idris, and others.

Screenwriters also had this ability to relate to issues of social and religious reality, in contrast to what had surfaced in artistic works several years ago. Most films became immersed in talking about crime and drugs, not as a treatment for them, but as an event that attracts the viewer. Even if it does not address an issue affecting society, or steal some ideas from foreign films, it addresses issues related to the society in which it was produced.

Although this quotation had previously existed from world literature, it was transferred with its color in the character of our society, as in the novel: (Crime and Punishment) by Dostoyevsky, and it was represented several times in Egyptian cinema with more than one title, and yet it was linked to our religious reality, Rather, Quranic verses were placed in the context of the dialogue, which was also done in the novel (Les Misérables) by Victor Hugo, and it was featured in more than one Egyptian film. The novel was also imbued with the Egyptian character, and the religious identity of the community as well.

There is no doubt that the topic of the fatwa and cinema is a topic that needs elaboration, but here we wanted to address it, to draw attention to it, and to draw the attention of interested researchers, to explore its depth, and to contemplate the extent of the influence of the fatwa on art, and the influence of art on the fatwa as well, and a quick article cannot cover all its aspects, but we We hinted at some important shots.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Al Jazeera.