78 years after the war, I am finally Japan August 8 at 23:13

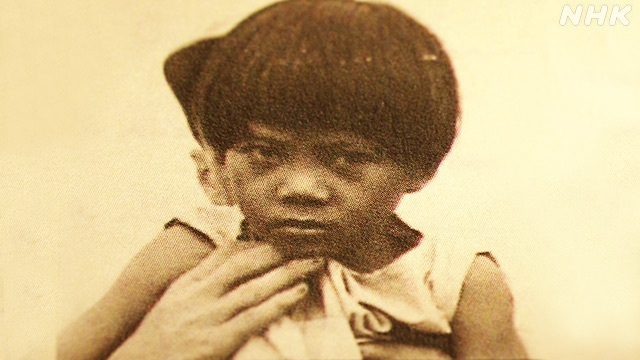

A little girl in the photo with a frightened expression.

Discovered last December, the photograph was among prisoner lists prepared by the U.S. military in the Philippines during the Pacific War.

The six-year-old girl at the time was the so-called "Japan leftover."

I have lived in the Philippines for many years without a nationality and have been seeking Japan citizenship.

Nearly 12 years after the war, the photographs changed the life of the 6-year-old girl this summer.

(Press and Video Center Yoshito Kuwahara, Manila Bureau Chief Noriyuki Sakai)

Still living in the Philippines

2 hours by car from Davao, the capital of Mindanao in the southern Philippines.

Passing through a vast banana plantation and climbing a steep mountain road from there.

She lived in a small, old-fashioned house woven from bamboo.

Welcoming us with a smile was 84-year-old Pelahia Diamona and Japan names, Haruko Hoshiko.

The house built on the slope of a mountain without running water or gas shows that Haruko has been struggling to make a living after the war.

Haruko says her father is Japan.

Why on earth did he end up living deep in the mountains in a stateless state without being recognized as a Japan person?

We decided to ask Haruko about her life so far.

A prosperous immigrant community built in Mindanao

Haruko's Japan people began to immigrate to Mindanao exactly 120 years ago in 1903, at the end of the Meiji era.

Pioneered by Japan immigrants from the wilderness of the jungle, the Davao area flourished as a production area for hemp, which was used as a material for military supplies and ropes for ships.

Before the war, more than 2,Japan <> people lived in the country, and it is said that the largest immigrant community in Southeast Asia was built.

Most of the immigrants from Japan were men and had families with local Filipino women.

Haruko's father, Suezo Hoshiko, from Kumamoto Prefecture, was one of them.

He and Marcelina, a Filipino, have nine children.

Haruko was born as the seventh child.

His father, Sueza, who came to the Philippines before the war, was successful in hemp cultivation and fishing, and raised his children as Japan people.

His family was Japanese conversations, and he lived a life without financial inconvenience.

A family caught in the vortex of war ~And to say goodbye to my father~

However, the Pacific War took everything away from the family.

On the island of Mindanao, Japan forces engaged in a fierce ground battle between American forces and Filipino guerrillas.

Haruko's family was caught up in the ravages of war, and her father, Sueza, decided to cooperate with the Japan Army as an interpreter.

Haruko

: "There was a Japan military garrison on the beach near my house, and Japan soldiers brought local residents suspected of being Filipino guerrillas to my father and had my father, who spoke the local language, interpret to see if there was any hostility."

At that time, if they were suspected of being guerrillas, they were often executed, and Japan and Filipinos deepened their hatred for each other.

When war finally approaches, Haruko and her family take refuge deep in the mountains.

Therefore, they continued to live as evacuees while being sheltered by indigenous people.

However, near the end of the war, in order to protect the lives of his family, his father, Suezo, decided to surrender to the American army.

The family was taken prisoner and placed in a camp where Japan people gathered.

Haruko:

"I was not allowed to leave the camp with wires, and I lived like a cow for six months in a building that could not be protected by the rain and wind."

What awaited me after the hard camp life was the separation of my family.

Haruko says she still can't forget that moment.

Haruko

: "My father wanted to take all the children to the Japan, but he didn't have permission. An American soldier told us that young children were not allowed to be taken with us," "My father was crying when we parted, and he left without turning to us."

Only his father and three older brothers and sisters, who at the time had reached the age of 15, were deported to Japan.

The mother and six young children, including Haruko, were stranded in the Philippines and became the "Japan people who remained."

Living in the midst of swirling prejudice and discrimination after the war

According to a survey by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at least 3800,<> children were separated from their fathers Japan after the war and left behind in the Philippines.

These children were forced to live in prejudice and discrimination as children of an enemy country that caused so many casualties to the Philippines.

After the war, Haruko's family burned down their home and all their property was confiscated.

He disposes of everything that shows his connection to his Japan and father, and hides deep in the mountains.

He recalls that he was unable to go to school and lived a life where he could not eat satisfactorily.

Haruko:

"Filipinos at that time hated people of Japan blood", "My neighbors didn't help me even though I had nothing to eat, so I became isolated", "Even my relatives didn't reach out to us and I thought I could starve to death", "There was no rice, I spent my time eating bananas and sweet potatoes. There were days when we had one meal a day."

About 10 years after breaking up with his father.

In distress, his mother suffered from heart disease and died at the age of 50.

The older brother and sister supported the remaining children by farming, and Haruko and the others managed to survive.

Haruko later married a Filipino man at the age of 27.

While cultivating a small field, he raised six children.

But there was no way out of poverty.

Haruko:

"My sister used to say that she wished she had gone to Japan with her father, and all the siblings left behind have lived with regrets."

We are Japan ~Our compatriots who have begun to raise their voices~

Anti-Japanese sentiment began to ease in the postwar Philippines in the 1980s, when economic assistance from Japan began in earnest.

The people who remained Japan, who had been hiding their births, finally began to speak up.

These remaining Japan formed Nikkei associations in various parts of the Philippines, and began to search for their fathers.

In the midst of these developments, Haruko also came to a turning point.

In 50, 1995 years after the end of World War II, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan conducted the first fact-finding survey of the remaining Japan in the Philippines.

Haruko and her siblings also participated in this survey.

Haruko said she hoped that she would finally be recognized by Japan people and meet her father, who had survived.

However, the survey was conducted only to ascertain the number of people, and the remaining Japan were not recognized as Japan.

Those who remain in Japan Philippines do not receive compensation or support from the state, even if they are recognized as Japan.

I want to be recognized as a Japan person.

When asked about her thoughts, Haruko replied with a strong tone.

"My dad is Japan, so I'm Japan too. It's natural. I've always prayed to see my father, brother and sister."

Patrilineal pedigree Japan and the Philippines

In the past, the laws of both Japan and the Philippines regarding the nationality of children used to be patrilineal.

In other words, if the father is Japan, the child automatically becomes a Japan nationality.

However, most remaining Japan cannot prove their paternity with their father.

After the war, fearing persecution and discrimination, they were forced to live in hiding, burning documents and photographs showing their connection to Japan father.

As a result, many of the Japan who remained were left stateless.

Acquisition of nationality Sites of unadvanced support

In order to solve this problem, there is an NPO in Tokyo that has been supporting the acquisition of Japan citizenship for the Japan past 20 years on behalf of the government.

This is the Philippine Nikkei Legal Support Center.

The organization has been finding and interviewing the remaining Japan people left in the Philippines.

Documents proving the connection to the Japan's father and other evidence are also sought on his behalf.

The collected evidence is submitted to the family court in the Japan country and permission to "register" a new family register is requested.

Over the past 20 years, more than 300 people have been able to acquire Japan citizenship, but by the end of March, 3,1780 people had passed away without being recognized as Japan.

According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at least 151 of the remaining Japan people currently confirmed alive remain stateless.

Representatives of NPOs are asking the Japan government to recognize their nationality en masse, without going through the court process that takes time to obtain Japan nationality.

Norihiro Inomata, Representative Director of NPO:

"Nearly 1 people died last year, and when I talk about candles, I feel that the flames are getting smaller and thinner. If this continues, the problem will disappear, not be solved. We need the government's in-depth support as soon as possible."

New Evidence Discovered ~A Girl Reflected in the U.S. Prisoner of War List~

Haruko is one of 151 stateless persons, but in December last year, an NPO discovered conclusive documentary evidence.

This is a list of Japan prisoners of war created by the US military in the Philippines during the Pacific War.

In this list of 1,8000 people kept in the U.S. Archives, there were records of Haruko and her family.

Norihiro Inomata

: "When we examined the list based on the testimony that he was taken prisoner at the end of the war, we found a perfect match. I realized once again that we can't move forward unless someone on the Japan side reaches out to us."

Acquiring nationality too late ~Wishes that came true and wishes that did not come true~

In early June, Haruko applied for employment (acquisition of Japan nationality) to the family court in her father's hometown of Kumamoto Prefecture through an NPO.

The prisoner list found provided strong evidence, and permission to work was only over a month.

In late July, we visited Haruko again with NPO representative Inomata Ms.

"I have good news for you today, I've been

recognized as a Japan," Haruko said with a

smile on her face, but she didn't seem to realize it.

Along with the report, Inomata handed over a photo.

"This is Miyoko, your older sister, who passed away in 2006," the photo shows her late sister, who went to Japan with her father and survived.

At least the photos were entrusted to me by Miyoko's family.

Haruko stared at the photo for a while.

Tears welled up in my eyes.

Haruko:

"I'm glad to be recognized as a Japan person, but I'm sad and lonely. I was so old that I couldn't see my father and sister again."

After the interview

Japan remain in the Philippines whose lives have been tossed around by the war caused by the country.

Its average age exceeded 83 years.

In recent years, there have been few cases where strong evidence like Haruko's can be found, and it is truly a race against time.

I sincerely hope that their earnest wish to "at least admit that they are Japan people while they are alive" will be fulfilled as soon as possible.

Haruko's tears ask us questions about issues that still persist 78 years after the end of the war.

After working at the Press and Video Center

Yoshito

Kuwahara in Kushiro, Okinawa, Osaka, Tokyo, and Yokohama, he is currently a member.

When he was a student, he was involved in the issue of Japan remaining in the Philippines. Since joining the bureau, he has continued to conduct interviews as his life's work.

Manila Bureau Chief Noriyuki

Sakai After working in the International Department and Sports News Department, he is currently a member.

The present and past of the neighboring Philippines are reported in the news.