Favorite Japanese Ryûsuke Hamaguchi claims the Palme d'Or on Nanni Moretti Day

Failure Sean Penn rolls it up again (there are two) and Ari Folman dazzles

The virgin-comforter scandal as a political revolution and scandal according to Paul Verhoeven

It

was hard

for

Nietzsche to

discover that much of what he had been told about the Greeks was not entirely true. One thinks of ancient Greece and it comes to mind, in addition to the beaches, that commitment to transcendent intellectualism that emerged from Socrates. Plato's teacher was a man devoted to the serious, to the serious, to what lives behind the shadows and hides at the bottom of caves. And one might think with it that all the residents then in the Peloponnese and neighboring islands were like that. And no. In fact, as the German of Dionysian tendencies soon realized, the Greeks really cared about

the surface, the fold, the feel of the epidermis.

"They worshiped appearances, they believed in forms, sounds, words", writes Nietzsche, thus

claiming for thought and life the art of the superficial and even of the frivolous.

Wes Anderson, who discovered himself in Cannes on Monday with his latest and much-anticipated achievement, has been pestering sequence-shot semiologists for years and giving trafficking moralists something to talk about.

And he does it with a cinema proud of its superficiality, happy in its geometric arrangement of gestures, landscapes and pastel colors. It is not that the American born in Houston is just a posh eccentric (which also) is that he is also with a conviction, a taste for detail and a balanced disposition of emotion that, in truth, is not noticeable. His is a stubbornly humanistic universe in which the characters act on an essentially beautiful principle of righteousness. His is a warm world where the icy arrangement of spaces always caters to an intuition with grace. Not necessarily ironic. His is a polite and fierce cosmos in its ethical demands on any aesthetic fickleness (or the other way around). His devotion to so-called frivolity is, if you will, '

Nietzschian

in character.

'; it is the way that his cinema gives itself to discuss the cinephile, stale and heteropatriarchal imposture of the given. Always against the grave and waxy voice of the one who knows.

His new film, which comes with a delay of more than a year (it was selected right here in 2020), is exactly what Wes Anderson's cinema has always been, but this time it has become an archetype. It would seem that in

'The French Chronicle'

(this is how the original '

The French Dispatch

'

has been translated

), the director has decided to agree with his critics to develop a film conscious of being a Wes Anderson film even beyond what that Wes Anderson himself never imagined. As it is.

The stories are folded into stories while the living pictures of infinite characters trapped in their hobbies pass through the screen in continuous acceleration.

Each scene, as if it were a vignette by Edgar P. Jacobs, rather than Hergé, is pregnant with a thousand perfect and small details destined to be discovered again and again.

The superficial thing is, we have arrived, the bottom;

frivolity is the way to disarm the always slightly fallacious impulse of the transcendent.

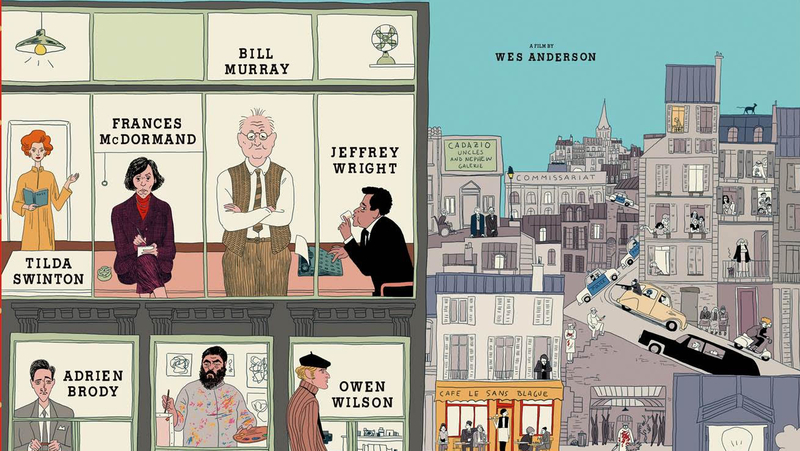

Image of the poster for 'The French Chronicle'.

The closure due to death of a magazine in the imaginary French city of Ennui-sur-Blasé (Villahastío de la Desgana) is recounted. Until there, a rich heir

(Bill Murray)

arrived long ago with the lunatic intention of telling everything. And do it in writing in a "weekly analysis of international politics, the arts (beautiful and not beautiful) and other diverse and varied events." Section by section, the film narrates a travel report on

Owen Wilson's

bicycle

;

a history of the greatest of painters by

Tilda Swinton;

a youthful and political chronicle with

Frances McDormand

as a conscientious analyst, and a gastronomic police adventure (it is so) thanks to the good palate and sense of risk of

Jeffrey Wright

. In between,

Benicio del Toro

(the painter),

Lea Seydoux

(the former's muse),

Adrien Brody

(the art dealer with vision),

Timothée Chalamet

(the young revolutionary),

Mathieu Amalric

(the food-loving detective) , Edward Norton (the kidnapper hungry for days) ...

If the aforementioned actors are added to the sets by

Stéphane Cressend

, the costumes by

Milena Canonero

and the music by

Alexandre Desplat,

it can be said that 'The French Chronicle' is a kind of summary of the '

Andersonian

'

corpus

that also wants to be a celebration of the own cinema. And even journalism. Each one of the stories bifurcates into a thousand others in an incessant provocation of

images that function as the vocabulary of a secret language and search words, each of them of its own color.

At one point, everything transforms into an animated tale that makes the dream of so many of seeing the adventures of Blake and Mortimer in motion come true.

If you will, it is a tribute to French culture through the most curious eyes of the best of American culture. In fact, the film covers each and every one of the topics (or archetypes) between 1950 and 1970 that have configured a way of seeing the world to which neither the cinema of Jacques Tati or Carné or Truffaut nor the tour nor

'La Chinoise'

.

All drawn and filmed in an infinite clear line.

In Anderson's latest film,

'Isle of Dogs'

, inspired by Richard Adams

'

novel

' The Hunted Dogs

', one of the dogs wailed to another about the difficulty of being a wild animal. The problem, the friend replies, is that according to what you have to start first. Too long trained, too long conscious of the virtue of order. Something similar happens to the protagonists of Wes Anderson's cinema, to all of them.

It is difficult for them to abstract from their condition as enigmatic and immaculately perfect beings.

They would like to be just human beings, but they are late. The very nature of cinema has made them what they are: the most faithful, detailed, fun and even cruel representation of any of us.

And that, indeed, is the miracle. From

'Bottle Rockett

' to peaks of timeless, Cartesian melodrama such as

'Journey to Darjeeling

' or '

The Grand Budapest Hotel'

to arriving here as an exaltation of all of the above, Anderson's camera moves across the screen like the pencil he drew a Tintin: with the same transparency and obstinacy.

It is about teaching the existential adventure of its characters from the meticulous description of what surrounds them and makes them what they are.

The idea is none other than to paint what's inside from the outside.

And in this game of thrilling landscapes, of passionate geometries, what is important is what is seen, the shape, the superficial, even the frivolous.

Everything that is taught could have been much more natural or wild, but for that, as the dog and even Nietzsche know, one must have been born before.

FROM RUSSIA WITH ... HATE

For the rest, the official section offered '

Petrov's Flu

' (

Petrov's

flu), by

Kirill Serebrennikov

, perhaps with the aim of compensating for so much happy reflection on an unreal France. The director of the vibrant, ambitious and desperate musical '

LETO

' (2018) now wants to tell what is happening in his country at the current date. And since he can't seem to find the right words for the enormity of the undertaking in doing so,

he can't think of anything better than offering himself up as a sacrifice.

Suddenly, the screen is soaked in the hallucinated despair of the director himself (persecuted as a homosexual by Putin) and what he succeeds in seeing is a violent world that struggles not to fall apart.

Post-Soviet Russia is transformed into a nightmare watched by the colossal fever of an eternal flu.

Serebrennikov says that with this film he tried to express what Russia represents for him and those who are like him. "I wanted to share our childhood memories and tell the public what we like, what we hate; I wanted to share our loneliness and our hopes."

The result is an exercise in

visceral and drugged cinema

that does not renounce anything: the vampiric genre is mixed with the hallucinatory dramatization of dreams that cannot be more than nightmares, and the memories function as wounds in the story of a man who drags his flu for an endless night.

Brutal and hopeless.

All that is light in Anderson, here is only shadow.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more

culture

movie theater

CineSpike Lee laments that 30 years after 'Do what you must' "black people are still being hunted like animals"

CineCannes does a PCR on the state of world cinema

The Japanese Ryûsuke Hamaguchi claims the Palme d'Or on Nanni Moretti's day

See links of interest

Last News

Holidays 2021

Home THE WORLD TODAY