ANGELICA REINOSA

@AngelicaArv

Updated Monday,5June2023-14:49

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Send by email

Comment

- Ranking The best-selling books of the week

The writer Paula Carballeira immersed herself in Saharawi camps as a storyteller. "My experience with refugees and books was incredible. The children were reflected in the stories and it was wonderful because it healed so many wounds," he shares. Her experience shows that children's literature is a tool for children to deal with situations in adverse contexts. At the same time, it allows the most privileged children to know other realities.

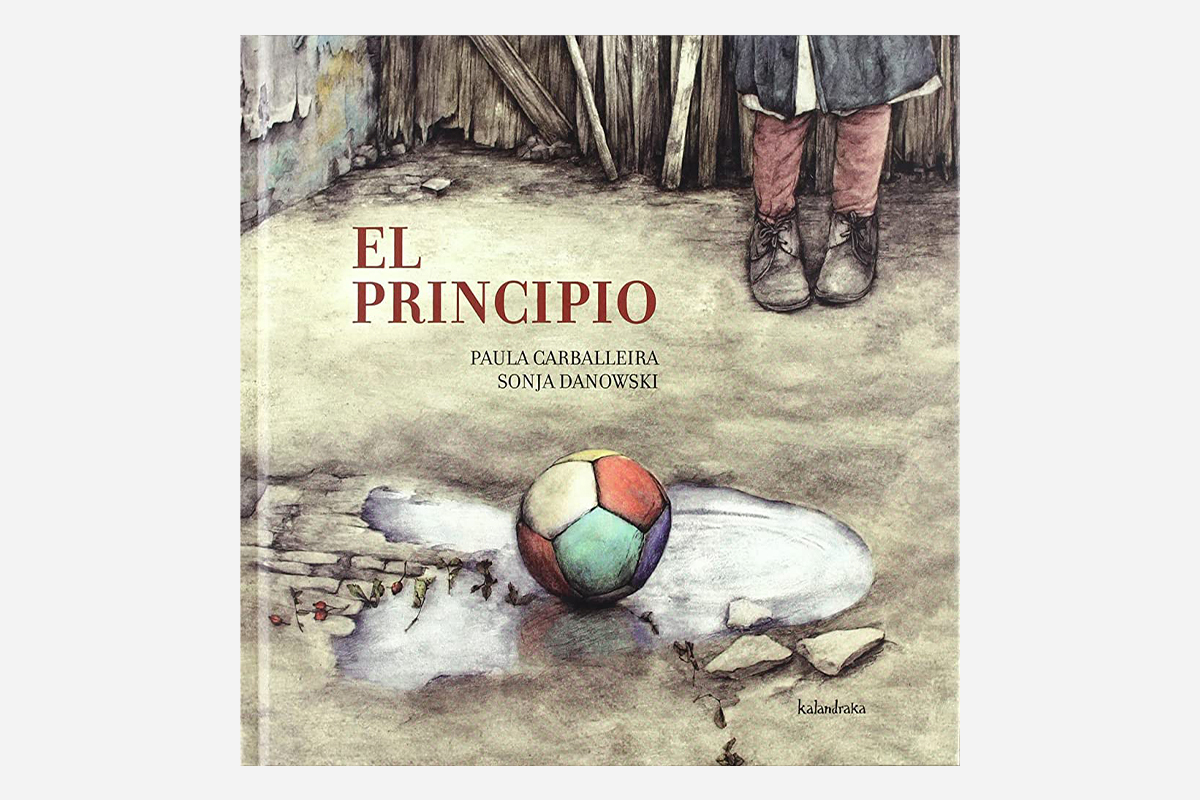

Carballeira is the author of The Beginning, a book, illustrated by Sonja Danowski, that reflects her conception of literature: "A place of open doors, where hope can be recovered." His text addresses the devastating consequences of war, but also the human faculty to resurface. Her narration is aimed at children and, far from traumatizing children by the theme, the author has verified the reaction she expected from them with the story: "They know that they are the future and that, although adults destroy everything, they will rebuild it thanks to laughter and their capacity for imagination".

A Long Journey is an illustrated album that reflects another reality: that of the exiles. Its authors, the writer Daniel Hernández Chambers and the illustrator Federico Delicado, narrate in parallel two stories of migration: that of some geese and that of some people. Birds get a happy ending; Hernández Chambers recalls that in several of the great works of the history of literature war appears as a context. That is why he is passionate about using it in his books: "In the tragedy that is a war, the best and the worst of the human being usually appear." The writer affirms that A Long Journey "can be read by both children and adults", but that "the ideal is that they do it together so that they can talk".

Writer Mar Benegas brings another unusual theme for a children's story: death. Illustrated by Javi Hernández, it is entitled The oldest dream and tells the doubts of a girl before dying. For Benegas, literature is "a refuge to endure a world that is falling apart, that hurts, that keeps the most wonderful and the cruelest," and also "a way to decipher mysteries, to understand them, to transform pain or to identify emotions."

The Principle

Paula Carballeira and Sonja Danowski

Editorial Kalandraka. 36 pages. 14 €

You can buy it here.

Traditionally, children's literature has dealt with thorny subjects, but with the purpose of leaving a moral or transmitting to children the consequences of disobedience. They were stories approached in a bloody and tactless way, like the tale of Little Red Riding Hood. However, many of these works were adapted, especially by Disney, to lead to a happy ending. With its evolution and the rise of illustrated albums, this literature began to have more artistic and leisure purposes, and became a cultural artifact. Why is it necessary to bring social problems to the stories that children hear or read? Why show, in media intended for entertainment, that in the world there are wars, migrations and deaths?

The answer is simple: because these situations occur in real life. Proof of this is that the war in Ukraine has been going on for more than a year. According to UN data, 8,000 civilians have been killed, in addition to the hundreds of thousands of soldiers who have lost their lives. At the same time, dozens of countries are going through other political, social or economic conflicts that force their inhabitants to flee in search of a better life. The office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recorded 89.3 million forcibly displaced people worldwide at the end of 2021. According to the Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid (CEAR), 2021 in Spain was of "historical figures in terms of refuge and asylum". And, of course, death can come to a child's environment regardless of their innocence. The hard months of the pandemic proved it.

Children are connected with a very critical spirit about the world and, at the same time, driven by their amazement

Adolfo Cordova

Childhood is often seen as a protected stage in which naivety must be kept intact. To this end, excessive efforts are made to hide problems from children. Susanna Isern, psychologist and writer of The Intruders, another illustrated album that addresses migration, explains that with overprotection the child "does not learn to manage his frustrations, nor the difficult situations in which he will find himself tomorrow." Along the same lines, Carballeira points out that it is inevitable that children will encounter facts that reflect social problems. "Our job as storytellers is to offer them that possibility of knowing a little more," says the author of The Beginning.

SMART READERS

"Children are connected with a very critical spirit about the world and, at the same time, driven by their amazement," shares Adolfo Córdova, journalist, writer and researcher of children's literature. He agrees with bringing sensitive issues to the little ones. He argues that they "ask themselves difficult questions about reality," questions that push "the history of children's literature toward that place where children are recognized as political subjects." In turn, Hernández Chambers emphasizes that "we must treat the child as an intelligent reader, which is what he is."

Even with all the benefits that children's literature brings to manage emotions and encourage children's ingenuity, many despise it. It is discredited with arguments such as "they are only books with drawings and little text", a phrase that Irene Álvarez Lata, co-founder of the Lata de Sal publishing house and founder of Tutifruti, hears assiduously. The expert Córdova considers that this look that some people have "is a reflection of the conception that there is of children: incomplete beings and in formation" and that, therefore, their literature "is also incomplete and lacks maturity". Different authors believe that the label 'childish' is one of its burdens. Córdova says: "Good children's literature is plain literature. I do claim to call it 'childish' because that adjective recognizes the place that the children themselves gained; but sometimes it gets in the way."

A long journey

Daniel Hernández Chambers and Federico Delicado

Editorial Kalandraka. 48 pages. 16 €

You can buy it here.

An aspect that detracts from the seriousness of children's literature is that, sometimes, the themes are developed in a sentimental way. Dealing with a difficult subject does not imply that a book is good. It may "approach the problem from a perspective that is still very white, privileged, even aseptic," as Córdova analyzes. However, it is these ways of dealing with topics that are most likely to be published.

Hard texts have a harder time getting on the market. The writer of A Long Journey comments that his book was rejected by five publishers with this argument: "It is a very good text, but it does not fit us because we have the illustrated album for more childish, funnier stories that make children smile." The same happened with The Oldest Dream, which "spent many years in the drawer, without finding a publisher." The reason why there is reluctance to publish these books is mainly economic. This is admitted by the editor Irene Álvarez Lata: "Of course they are much more complicated issues to sell. No one carries a war book to a birthday. Logically."

RISKY PUBLICATIONS

Publishers such as Lata de Sal or Tutifruti circumvent the situation and try to address difficult issues implicitly. Álvarez Lata explains: "Everything complex needs to be treated in a simple way. I try to convey those themes in a way that can be reached in sales." There are also publishers that bet on publishing hard topics, even when they are addressed explicitly and aware that sales will not be fruitful. "When I sent the book to Kalandraka they told me the nicest thing a publisher has ever told me: 'we know it's going to be very difficult to sell it, but we're going to publish it,'" recalls Hernández Chambers.

Of course they are much more complicated issues to sell. No one takes a war book to a birthday

Irene Alvarez Lata

Bárbara Fiore Editora (BFE), in fact, is a publisher that is focused on addressing sensitive issues in its illustrated albums. Elisabeth Pérez, project manager of the publishing house, highlights one of the tasks of the company: to forge a critical look by bringing all kinds of stories to children. "Migration or war for certain types of children is day-to-day. So it is necessary to show these realities to children, whose normality is less dramatic, so that they develop emotions such as empathy and solidarity," shares the BFE editor.

It is important to note that reading mediation is very necessary with sensitive topics. Evelyn Arizpe, professor at the University of Glasgow, researcher and expert in children's literature, has launched different projects in disadvantaged environments. One of them was the program Reading with migrants, to promote the pleasure of reading and the questioning of certain topics in an aesthetic way: "It makes them reflect. It's a space where that fictional framework allows them to delve into the story, without it affecting them in a negative way." While basic needs should be thought of first in exiled children, keeping culture in mind is "part of that right to feel safe, welcomed, and cared for; And a book can express that."

Arizpe explains that activities such as reading aloud, contemplating the illustrations and literary conversation "help develop the ability to construct meanings, to go beyond what is in the coded word." The expert argues that being a reader goes beyond decoding words: "It is understanding the deepest meanings of a text and reacting with questions."

The Intruders

Sussana Isern and Sonja Wimmer

Editorial Tierra de MU. 48 pages. €16.50

You can buy it here.

In the reading workshops with exiled children they do not only use books with themes that remind them of their situation, but they try to make the experience with the stories pleasant. "It's not about knowing what they've been through, but about enjoying that moment. We do not want to put pressure on them, but to open a form of dialogue. This takes time. You have to start with softer books and work your way," shares Arizpe.

The importance of adults is fundamental to address some texts. As Córdova specifies, "while a good book can open many doors, the hand that opens the door is more important." The expert has also had the opportunity to work in the context of migration, but from another aspect: that of children who stay while their parents leave. "It is another way of thinking about migration, which often focuses on those who left, on the flight, on the journey, on the arrival; and not in those who remain, who are also experiencing another effect of the diaspora."

If we want the new generations to be better than ours, we have to open the doors to culture from the first moment. And the best way to do that is through literature.

Daniel Hernandez Chambers

Children's books have very varied uses, even beyond didactics in the classroom. The Ibero-American Association of Short Story Therapy, for example, points out that they work on "the art of healing through stories", as stated by its president and founder, Lorenzo Hernández, who is also a psychologist and psychotherapist. From the association argue that a given book can help a person, of any age, to overcome a critical moment.

Story therapy is often criticized for its therapeutic intent. In fact, Evelyn Arizpe distances herself from her and says: "It has its place and I think it is important that there are people who do it, but they have to be trained." Mar Benegas also points out: "Sometimes we pretend that the processes are mechanical, we look for the magic formula, the 'open, Sesame', that book that 'serves for'. We forget that the soul doesn't work like that."

The oldest dream

Mar Benegas and Javi Hernández

Editorial Bululú. 40 pages. €17.90

You can buy it here.

Lorenzo Hernández replies that he does not pretend that story therapy is an absolute tool: "I would not cure anyone, even psychotherapeutically only with stories. The story can be an adjuvant, a good supportive therapy." This defender of story therapy does not conceive what some authors claim: that they do not seek to give a message or pursue any other objective beyond that of creating a literary work or entertaining. "Why do they write stories that have a moralizing intention? If the author does not want to say anything, then why does he deal, for example, with the transcendence of death in his text? A literary work is good in itself, but if you also know how to give it other uses, why refuse what is a good?", asks the president of the Ibero-American Association of Short Story Therapy.

Children's literature offers an infinite number of possibilities and themes. However, in Spain it is still not valued enough. It's a sentiment shared by Susanna Isern: "We still don't have our rightful place. Childhood should be valued as the most important thing we have and, therefore, we must take care of the books they consume and their authors." Álvarez Lata indicates that "more is edited than read", but recognizes that "there are more and more people who like children's literature, who appreciate it and distinguish it".

There is still some way to go. Meanwhile, writers, illustrators, publishers and mediators will continue to foster a passion for literature from an early age. As Hernández Chambers concludes, "if we want the new generations to be better than ours, we have to open the doors to culture from the first moment. And the best way to do that is through literature."

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Learn more

- literature

- Book Fair