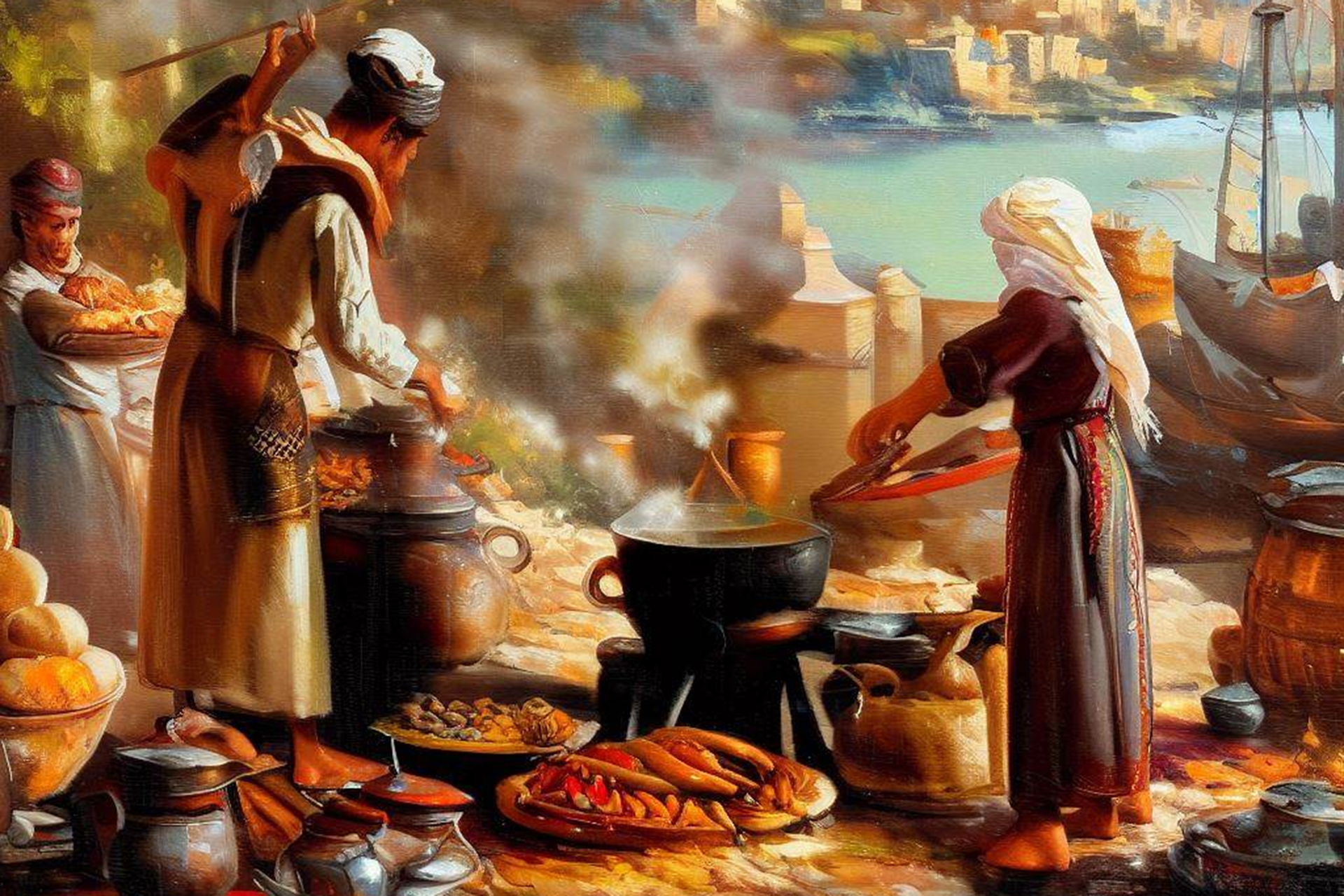

Do you expect to mention "Qataif" and Syrian and Iraqi dishes you know in an ancient manuscript from the Abbasid era?

Muhammad bin Hassan al-Baghdadi (d. 1239 AD) wrote the "Book of Cooking", explaining the Abbasid food arts and types in a poetic language, including citrus, "swats", "fryers", "nawashifs", "haras", "tannouriyat", "matajnat" and "board", as well as sambouseks, pickles, annals, etc., and what is cooked belongs to the culture, in When everything that is raw belongs to nature.

It is commonly said that man is the only being who cooks, and in the eras of Arab civilization the books of cooking were famous and popular, and unlike the book of Baghdadi, the famous "Book of Cooking" by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq, Ibn Masawayh, Ibrahim bin al-Mahdi, who wrote poetry, Ibn Daya, Ibn Mandawayh, al-Harith bin Bashnar and others, in addition to the book of drinks by Miskawayh the philosopher, who also wrote a book on cooking, and "Foods of the Sick" by al-Razi.

The arrival of the Mamluks to power in Egypt and the Levant contributed to the flourishing of literary writing about cooking, as soldiers enjoyed cooking and serving food, and cared for cooking pots, carried them with them and defended them even in times of war.

Culinary care continued within the Mamluk and later Ottoman traditions until the era of European colonialism, which brought its cooks with it, as the "culinary literature" that had been a feature of Arab culture for centuries declined.

Many

ancient cultures produced cookbooks, but the rich Arabic manuscripts that survived in the Middle Ages are unparalleled; during that era, there are no contemporary Western and Eastern cultures that produced so many cookbooks like the Arabs, according to Iraqi cookbook researcher Nawal Nasrallah.

Nasrallah argues that the rise of a thriving elite of chefs and gourmets who indulged in fine dining and culinary activities, and in reading and writing about food in prose and poetry, made cookbooks highly sought-after at the time, a trend that increased the prosperity of Baghdad's papermaking and stationery business in the ninth century, according to her study published at the American Institute for Oriental Studies.

Of the many writings that have spread in this era, only ten have survived the ravages of time, hailing from Baghdad, Aleppo, Damascus, Cairo, the West and Andalusia, ranging from full volumes of cooking to small, limited-page brochures, and giving a glimpse into the rich food culture of countries where many still maintain ancient and established culinary traditions.

The first book entitled "The Book of Cooking" was compiled by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq in the second half of the tenth century in Abbasid Baghdad, and its full title was "The Book of Cooking, Food Reform, Food and Foods Manufactured Foods Extracted from Medicine Books and the Words of Chefs and People of Pulp", and is considered the oldest cookbook that came to us from the Middle Ages, and is characterized by its breadth, comprehensiveness and cooking choices that were often commissioned by a rich patron (possibly Saif al-Dawla al-Hamdani) It was intended to describe the dishes and foods eaten by caliphs, princes and dignitaries.

Designed to resemble today's tabletop cookbooks, fascinating poems and entertaining tales mixed with recipes served the same purpose as today's food books, and encompassed many food-related topics, including the health benefits of food dishes, and their health effects on the body, heart or mood.

In the chapters of Kitab al-Warraq, chapters on what corresponds to young people and elders in terms of cooking colors, dairy and cheese, cereals and bread from wheat and rice, and what corresponds to the ailing stomach of eaten foods, grilling in tandoor, grilling meat in pots, managing water drunk with ice, and others.

The manuscript of Ibn al-Sayyar, the Finnish orientalist Kai Ornberry, and his Lebanese colleague Sahban Marwa in 1987 was edited from a manuscript at the University of Helsinki, and the complete manuscript contained more than six hundred recipes that were divided by the author for more than 130 chapters, and included sweets, foods for the sick or Christians fasting, recipes for cleaning hands, table etiquette, regret, after-meal activities and eating poems, in addition to kitchen utensils suitable for each food, tips to get rid of food odors after cooking, and cleaning hands, teeth and mouth.

Arabic

CookbooksAl-Warraq's book was not unique, as it was based on many of the works that preceded it, including the poems of Ibrahim bin Al-Mahdi in cooking, and the books of Ibn Masawiya, Ibn Dehghana and others, and Al-Warraq mentions in his book 15 different types of bread, detailing the way each of them works, and mentions food that resembles the Jordanian mansaf, a dessert that resembles Iraqi cakes "Kleja", and recipes for grilled meat that are similar to the current prevalent.

Al-Warraq did not neglect "vegetarian food", as he explained vegetarian dishes that he called "forges", and his book also included many sweets such as "Qatayef", known by its name until now, salted nuts, raisins, wine drinks and digesters.

The book included many tips for healthy nutrition, including eating fruit before and not after food, and not sleeping long after it, and also included proverbs, anecdotes, stories and tales about the nights of the caliphs and princes that were full of luxurious foods with a smart smell.

Like al-Warraq, the treasure of benefits in diversifying tables is also popular in Mamluk Egypt, and although its author is unknown, it is the only surviving cookbook from Egypt, and the last major culinary volume from the entire Arab-Islamic region of the 14th century.

Nawal Nasrallah has achieved many of the book's recipes, including pickled fennel, turnips, olives, lemons, sobia and beans with meat, and many popular Egyptian dishes so far, such as molokhia, okra, kishk, sambousek, omelette, mullet, taro, taqlia and others.

In addition to food recipes, the book included Mamluk foods famous in Cairo, including sour, sweet, fried, grilled, fish, drinks and digesters, as well as recipes for perfume, soap and incense, and the names circulating in the book indicate the origins of the unknown author and his Egyptian dialect.

The author's chapter on sweets contained 81 recipes that are evidence of the abundance of sugar in the Egyptian market and its reasonable cost at a time when sugar in Europe was still a rare commodity used in small quantities in medical treatments.

The book contains recipes for hand washing preparations in addition to essential oils, incense, methods and materials for cleaning food places from suspended food odors, and also includes a description of more than thirty types of distilled water, which is used as perfumes and treatments, and can be prepared in home kitchens.

The manuscripts are indicative of the rich food culture of major Arab cities, such as Baghdad, Damascus, Sana'a and Cairo, a rich and diverse culture that continues to influence the cuisines of the modern world.