Between the early 17th and mid-19th centuries, the presence of Islam in North America was linked to African slaves brought from West African countries to work on agricultural lands.

While the existence of a large number of ancient African Muslim slaves may not be known to most Americans today, researchers believe they left their mark on American culture even before it became a state, as some of the first immigrants to this land were Muslim immigrants forcibly transported as slaves in the illegal trade that spread across the Atlantic at the time.

Although this important historical period is of little interest to American and Muslim historians alike, American sociologists have estimated that between 15% and 30%, or as many as 1,2 to <>.<> million slaves in America, were Muslims, according to the study "Muslims and America's Making" by the American Academy of Barchios Rashida Muhammad, who specializes in the history of Muslim slaves in America.

Forty-six percent of slaves in South America were abducted from areas of West Africa that had large Muslim populations, Khaled Beydoun, an ethnographer at the University of California School of Law, told Al Jazeera English.

Enslaved African Muslims in the New World were known for their strong desire to follow the teachings of their religion and meet the demands of their faith, especially the Ramadan fast, which was a hard suffering, as well as the performance of prayers, halal food and social duties, and historical sources recorded this clearly, both in the United States of America and South America and the Caribbean.

Prohibition of Religious Assembly and Activity

Muslim workers on plantations and in areas such as the southern states of America and Brazil have sought to follow religious duties, retaining cultural and autonomy in the face of sweeping slavery laws that completely dispersonalize them, link religious activity to rebellion, and enact legislation limiting their practice.

U.S. laws in this era banned the gathering of slaves in the southern states of Virginia, and brutally enforced penalties for assembly, which affected enslaved African Muslims celebrating the beginning of the month of Ramadan, eating iftar and performing taraweeh in groups.

Although the Qur'an allows Muslims to abstain from fasting in case of travel and hardship, many enslaved Muslims chose to fast despite the harsh conditions, as a kind of assertion of their own identity at the time.

Many enslaved Muslims held Ramadan prayers and worship in private slave quarters, gathering for iftar, even though this violated arbitrary slave laws restricting assembly of any kind.

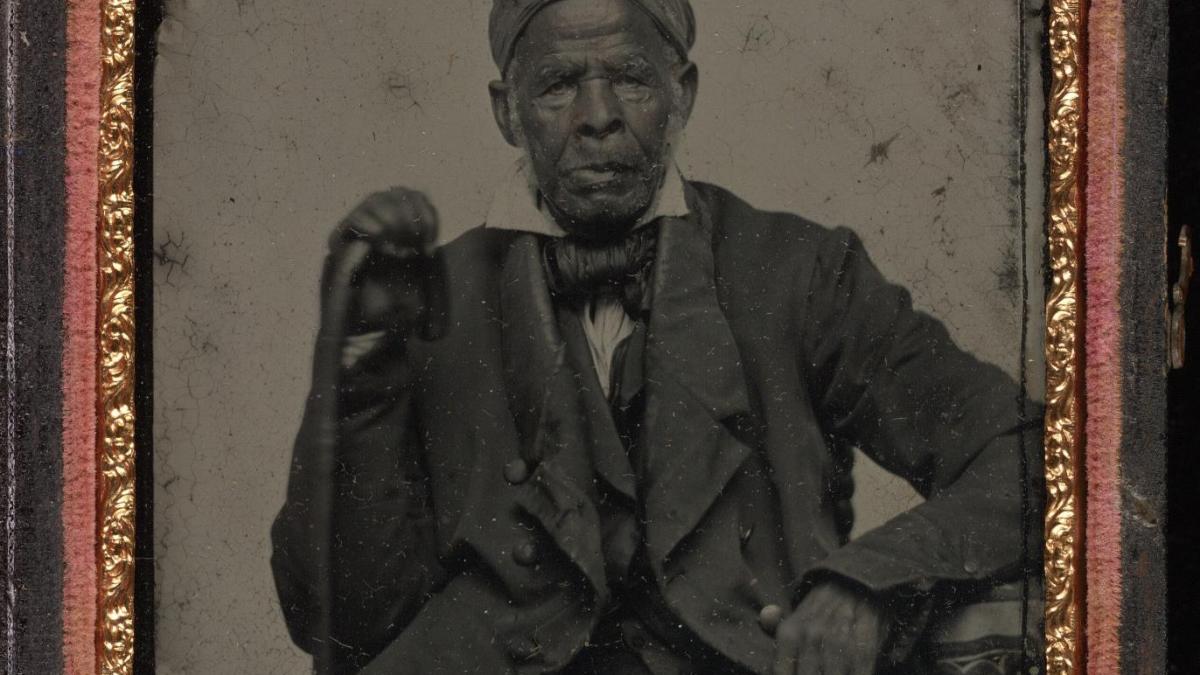

Early American Muslims faced challenges and consequences when practicing their faith. Like Ayuba Souleymane Diallo, who was kidnapped from his African country and sold as a slave to work on tobacco plantations, where he was abused while praying, escaped and was arrested.

Many were forced not to fast in Ramadan while many converted to Christianity ostensibly, to protect themselves and their families from the brutality of masters such as Lamine Kebbé, who converted to Christianity in order to secure a return to Africa through the American Colonization Society.

Others, such as Ayuba Souleymane Diallo, refused to budge from their faith. The slave owner was so impressed that he was released and returned to Africa, according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In recent writings such as Sylvian Diouf's Servants of God: Enslaved African Muslims in the Americas, New York University Press, 2013, and Allen Austin's African Muslims in Prewar America: Stories and Transatlantic Spiritual Struggle, Routledge Press, 2011, have many stories about African Muslim slaves suffering Ramadan fasting in the New World.

Sociologists estimate that up to 30 percent of African slaves brought to the United States, from West and Central African countries such as Gambia and Cameroon, were Muslims. Among the difficulties they faced were those related to their faith, according to Saeed Ahmed Khan, an academic at Wayne State University.

Khan adds that African slaves were forced to abandon their Islamic faith and practices, separating them from their culture and religious roots as well as preparing them and converting them to Christianity.

The struggle against slavery by fasting

Enslaved African Muslims in America considered fasting to bring them a kind of connection to their communities of origin and religious culture.

In Brazil, free and enslaved Muslims enjoyed fewer restrictions on their daily lives than their North American counterparts, they are allowed to eat together and go to their places on occasions such as the crescent moon survey and iftar.

Brazil's non-Muslim population observed how Muslims exchanged gifts during fasting, and Brazilians understood it as "saka," a misname from the Arabic Islamic term "zakat."

Another struggle among enslaved Muslims of African descent was halal food that was difficult to obtain, as pork was the least expensive and most abundant meat, and they were encouraged to consume alcohol to assuage fears.

Fasting was thus not just an obligation and religious worship performed by enslaved African Muslims in America, but a way to assert their independent identity and a kind of struggle against being considered private property and slaves on masters' plantations.

Although U.S. Muslims now constitute the most diverse Muslim community in the world, the history of Muslims in the early New World still lacks recognition and appreciation.