UNDER REGISTRATION

QUICO ALSEDO

PABLO HERRAIZ

Madrid

Updated Friday,26May2023-02:34

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Send by email

See 1 comment

- Editorial Child suicide: a drama that requires maximum attention

"Mom, what if we go home?" asked Rodrigo Pujol, 14, to his mother on February 22, 2021, both of them still in the car, parked very close to Arturo Soria Street in Madrid.

"And I tell him to give the center one more chance, and if in a few days we see that it is not going well, we look for something better. Then I accompany him to the door, we hug and I see him enter the reception and leave his things, his backpack and mobile, at the entrance gate. It's the last time I see m alive

I little son, my beloved son, that exceptional being that no one will be able to discover anymore."

Four hours later,

Mayca Girl

You receive a message from

Rodrigo

on your mobile. A message in which the boy, very intelligent but with socialization difficulties,

clinically depressed

or and in treatment for a year, he says goodbye.

"It was not your fault," reads the message, which ends with a freshness that can only come from a wounded but still young youth: "I hope you live an exciting and happy life for me."

Mayca delves into terror. Rodrigo should not be able to access his mobile in the

ITA Clinic

, where she has left him that morning and where he has been dealing with sadness from 14.00 to 19.00 for two weeks.

The woman succeeds in calling the center. The operator tells him, with total tranquility, that Rodrigo has already left, an hour ahead of schedule. God, how is it possible? They were perfectly aware that the boy had flirted with the idea of getting out of the way. His family had even fished him a farewell letter months earlier. That's why they had trusted this clinic to help him better... But a minimum deception has been enough to facilitate his escape: an educator will declare that same afternoon that the boy told her that his father was coming to look for him and they opened the door without problem.

Find out more

Mental health.

Mar's suicidal adolescence: "I tried many times, I felt that I should punish myself, that I had no right to anything"

Editorial staff:

QUICO ALSEDO

Brea del Tajo (Madrid)

Editorial staff:

PHOTOS: ANTONIO HEREDIA

Mar's suicidal adolescence: "I tried many times, I felt that I should punish myself, that I had no right to anything"

Adolescence, depression and suicide after the pandemic.

"The system is failing us, the hopelessness is growing"

Editorial staff:

RODRIGO TERRASA

Madrid

Editorial staff:

JOSETXU L. PIÑEIRO (ILLUSTRATIONS)

"The system is failing us, the hopelessness is growing"

The hysteria is uncontainable.

Mayca

You know what

Rodrigo

He has an application on his mobile that allows him to locate him and, at the same time, writes at full speed to the child's previous psychologist, to ask him where he could have gone. "Train," replies briefly the professional, who is in full session and to whom Rodrigo had confided his darkest thoughts. "Train."

Mayca calls the

Police

, to the father, takes the car from his house in

Torrelodones

, 30 kilometers away, and desperation drives her towards Madrid.

But where the mobile places the kid, in the

Metro Arturo Soria

, the police, looking for a boy in jeans and a black sweatshirt, only find a backpack, with another suicide note inside. A note very similar to the one that alarmed his parents months ago.

Arturo Soria

It is filled with ambulances and police cars. Authorities are slowing convoy traffic between that station and the surrounding area. Several agents walk the tunnels with flashlights. Fear floods the scene.

But Rodrigo has been faster. His body already rests under one of the trains, and his death swells an unbearable list.

: suicide attempts

in minors

have multiplied by 25 in

Spain

in the last 10 years.

In 2020, 310 were registered. Two 12-year-old sisters committed suicide in Oviedo last Friday.

Two others tried - one of them succeeded - in February in

Sallent (Barcelona)

. In 2022, 906 attempts were registered nationwide, the highest number in the last decade.

What's going on with our guys?

"We did not know how to see it in time," Mayca writes several months later, with the "broken soul", in a letter that goes viral in July 2021 under the hashtag

#GraciasaRodrigo

. Then, the family shows its pain – "today I want to shout to the world and I have every right," the letter begins – and invites society to reflect: "We have been victims of misinformation, stigmatization and undervaluation of mental health."

Today, EL MUNDO uncovers the new nightmare, suicide apart, in which the family of Rodrigo Pujol lives, who has been struggling with Justice for two and a half years without getting responsibilities purged. "That improperly opened door prevented us from continuing to fight for him, for our beloved son," Mayca explains.

It wasn't your fault. I hope you live an exciting and happy life for me

De nuevo, ¿cómo es posible? A la muerte del chaval, el

Juzgado de Instrucción 18 de Madrid

abrió las habituales diligencias ante cualquier fallecimiento en que no concurran causas naturales, pero las cerró en menos de un mes, sin siquiera dirigirse a la

Clínica ITA

a pedir información. Eso lo tuvieron que hacer Mayca y Víctor, los padres, instando un procedimiento civil para que el juez de Primera Instancia 43 le pidiera al centro los datos esenciales: quién dejó salir al niño y por qué.

La clínica ITA -"que desde los días posteriores al suicidio no ha vuelto a ponerse en contacto con nosotros", dice la madre- "se negó desde el principio a facilitar la información al juez, sólo terminó dándola a regañadientes cuando les obligamos por vía civil", dice

José Martín

, abogado de la familia.

El juez de Instrucción 18, pese a tener la evidencia en la mano de que la clínica dejó salir al chaval aunque sabía que tenía pulsiones autolíticas, cerró la causa negándose siquiera a investigar. Fue ya casi dos años después, el pasado enero, cuando con los documentos y recursos en mano al fin pidió un informe al forense y más tarde ordenó declarar como investigada a la trabajadora del centro que dejó a Rodrigo caminar hacia la muerte. "Llovía mucho y nos dijo que su padre estaba fuera", explicó sobre el fatal error.

Es la defensa que la clínica ha ofrecido a preguntas de este periódico: que llovía mucho, «los padres esperaban a sus hijos en los coches», y que Rodrigo salía a las 18 horas, no una más tarde. En sus escritos al juzgado alega otra: "ese día", justo ese maldito día, Rodrigo no manifestó "ideas autolíticas", así que no había por qué sospechar.

"Mienten en todo ello"

, dice Mayca Chica. "Apenas llovía, no podían dejar salir así como así a un chico con pulsiones autolíticas y salía a las 19 horas".

Tercia José Martín, el abogado: "La compañía de seguros nos ofrece 150.000 euros y olvidarnos del tema, pero la familia quiere justicia".

But Rodrigo: a handsome, "sarcastic", sensitive kid. What can your case teach us? "From kindergarten we saw that he was not like most: he did not want to stay to play, the end-of-year shows were terrible, he did not play football in the yard, it was difficult for him to make friends ... He was also very affectionate with us, he liked to read and play Play, he got good grades ... But he was becoming isolated. That isolation made him different and that was damaging his self-esteem."

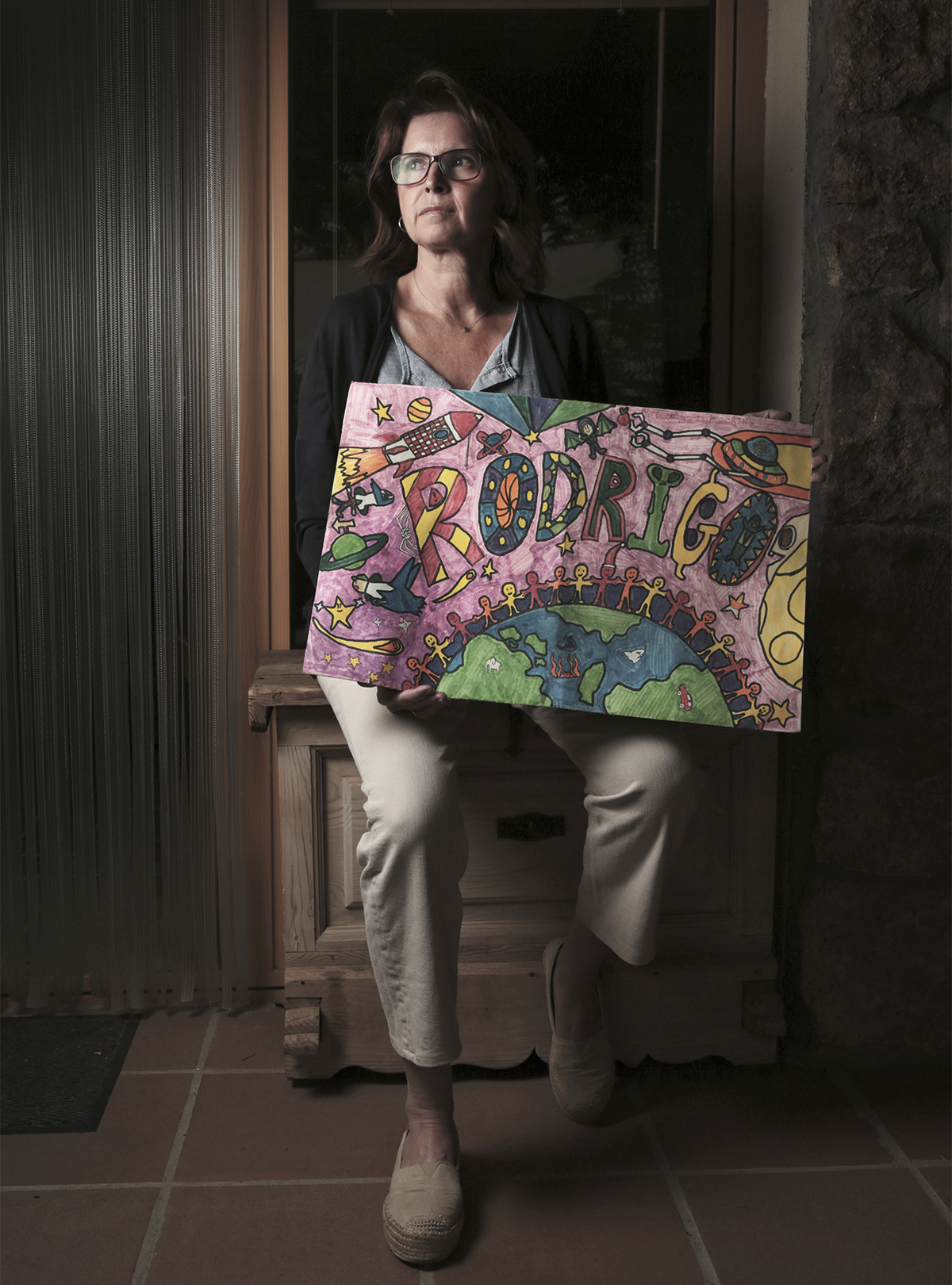

Mayca Chica, with a drawing made by her son Rodrigo, in the family house of Torrelodones (Madrid).

JOSE AYMA

The family itinerated – from their three to six years old they lived in

Belgium

, and from nine to 12 in

France

, following the obligations of the military father-, and with it the little life of Rodrigo. Until in the rubicon of adolescence everything went up a step. "I didn't understand the world: if someone sneaked into the dining room queue, or if they made fun of the substitute teacher, or climate change... Everything affected him a lot," says Mayca. "I now know he was an undiagnosed highly sensitive person. He complained about how bad people were, he said we were the virus of the planet... He was a loved and supported child. He told us his feelings. We knew he was having a hard time, but who hasn't had a hard time in life."

When she was 12 years old, she threw herself away by going to a psychologist. "It didn't help much, or they didn't fit in well or he didn't open up," says the mother.

A test at school after the covid lockdown helped him warn his parents: "I feel very bad, I've been looking online and I think I've been depressed for years." The psychiatrist confirmed the self-diagnosis. Severe depression: therapy and drugs that don't work, "not even in adjustment."

Until, on December 30, 2020, Mayca finds a farewell letter in her bedroom. The fantasy of the end: "He became very nervous and refused to tell us anything. He told his sisters that it was a thing from before, that he didn't think about doing it anymore."

The psychologist also warns of autolytic ideation. Rodrigo is already very lost. One morning, hours after dropping him off at school, the mother receives a call from the center: the boy has not gone to class. He has spent the morning wandering around the bush. The hardworking and responsible child has been disconnected from the classroom for weeks. "He could no longer concentrate on watching a series, only his mobile phone evaded him."

It is the psychologist who recommends the ITA Clinic. Rodri needs daily follow-up.

There they obviously tell everything.

Mayca

, who even two and a half years later narrates his experiences with Rodrigo in a trance, goes out of his way for his young son.

"It starts going on February 8, 2021. He came home saying that he doesn't think it's the best thing for his case, that he's all very focused on eating disorders and that in the afternoon no one stays." A few days pass that the family expects and wants to adapt, and then 10 more confined all because one of the sisters catches Covid.

Days later Rodrigo is gone.

"It's obvious that we're seeing a very serious boom in autolytic behaviors," he says.

Jose Carrion

, psychologist specialized in minors. "Factors? One is the pressure that society exerts on kids to be a certain way. In social networks, especially those of a visual nature, children are permanent witnesses of realities that are not theirs, and that causes them an important conflict of frustration, of not being up to it, of fear of not arriving. "

In the case of Rodrigo Pujol, the confinement of Covid could have played a role. "It dislocated many, especially the little ones," says Carrión, who continues with his analysis: "They are also hyperprotected generations, who perhaps have not developed resilience tools to get ahead and in the face of any setback they give error. Generations too uplifted by the speech of their parents and by what is expected of them, and little aware that life is not the absence of problems, but the management of those problems.

And one more factor, explains this renowned professional: "I do not want to talk about call effect, but there is an adolescent culture that includes autolytic behavior in pictures of borderline personality disorder, in pictures of attention calls, and in situations of despair, where the inputs that kids receive can be facilitators to start an autolytic behavior, and even conclude it."

Are there weapons to deal with this? "The public health teams are very well trained, with their 'mires' and their residences, but they are very scarce. If a psychologist only attends you every 45 days, you cannot achieve goals. The resources are very insufficient," concludes Carrión.

We return to

Mayca Girl

: "Mental illness is not seen and until recently there was no knowledge because it was not talked about. I have three children and the doctors have only asked if they have a fever or cough, not if they felt well and had friends. I never said anything either. Physical, mental and social health are intimately linked and we have not treated it that way. For example

Rodrigo

He was very stooped and when I took him to the traumatologist he told me that he was fine, that he simply needed to play sports. Not long ago I learned that the internal pain that depression produces is so strong that it makes them slouch ... My poor boy. We failed him, by the time we realized it was too late."

He continues, "I feel guilty for trying to fix it so much that I think I convinced him it was broken. I pointed him to tennis, swimming, judo, robotics, self-defense, theater... In case something hooked you. Maybe they were stones of failure that I put in his backpack."

That incombustible love led Mayca to repeat to the child: "You have to change the chip", "enjoy what you have" or "you have to do for life". He, of course, would say, "Mom, you're asking someone who has cancer to stop having it."

One day

Rodrigo

flew out of the nest earlier than expected. And life, unexpectedly, followed: "After that time of anger, pain, guilt, immense sorrow... You start to have moments when you're not so bad anymore. You pass in front of a shop window and you want to try on that sweater. But am I dumb? With what has happened! You feel guilty for not feeling terrible all the time."

It does not help, of course, that Justice has so far looked the other way: "We know that the clinic is not guilty of his death, but of giving him the opportunity. That open door he must have interpreted as a sign from the universe. That's not a mistake, it's a push. And it cannot go unpunished. Insurance money is not enough. I give them double for just one more day with my son," says this mother.

That fateful day, from the ITA Clinic, they call

Mayca Girl

the psychologist, the psychiatrist and the director. "All three of them saying they're very sorry and acknowledging their guilt. When they ask me if they can do something for me, I say yes: send me the documentation about my son, the questionnaires they had asked him. They tell me they will," he breathes. "But they haven't delivered. They have never called again."