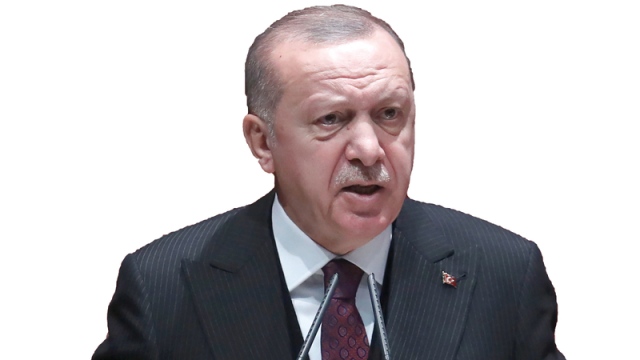

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, after the summit celebrating the 70th anniversary of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), revealed a clear message indicating Ankara's determination to impose itself as an independent force on the world stage. He said before members of the Turkish community in London, the month before last: «Today, Turkey can start a process to protect its national security without asking anyone’s permission», and this statement represents a clear example of the strict, often unilateral, Turkish foreign policy Erdogan has adopted it in recent years. In October, Turkey challenged the Western allies, to send forces to northeastern Syria against the wishes of NATO. Two months later, the Turkish president pledged to deploy troops in Libya, despite the United Nations' call on the world to respect the arms embargo.

Turkey's desire to look for greater influence in its neighborhood is not new. But her bold and growing pursuit of her goals has infuriated European and Arab leaders alike. "It seems that Turkey is getting more aggressive day after day," says a European diplomat, adding that "its demands are getting bigger."

Turkish activity in the Middle East and North Africa began to increase after the Arab uprisings that rocked the region in 2011. Turkey provided support to groups fighting the Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad, in Syria, and supported the isolated Egyptian President, Mohamed Morsi. Ankara hoped, through these interventions, to restore its influence and glory in parts of the former Ottoman Empire, but its gamble failed when Russia came to the rescue of the Syrian government, and after Morsi's isolation in Egypt.

Analysts say that a new approach in the interest of direct military action emerged after the failed coup that Erdogan was subjected to in 2016, which in turn weakened the autonomy of the army, and enabled the Turkish president to consolidate his authority. Since then, Turkey has launched three separate military incursions into northern Syria, including the controversial October attack on Kurdish militias, which fought ISIS on behalf of the United States.

Elsewhere, Turkey sent warships to prevent European oil companies from drilling for gas in the eastern Mediterranean, and defied the wishes of NATO allies when it bought an air defense system from Moscow. Erdogan - who visited Algeria, The Gambia and Senegal - also sought to broaden Turkey's relationship with the African interior.

The most surprising step by the observers, was the decision of the Turkish president, last month, to go deeper into the Libyan conflict, after his decision to send military advisers and Syrian mercenaries supported by Turkey, to support the Tripoli government.

Through this intervention, Turkey aims to have a seat at the table of talks on the future of this war-torn country, but this military support has drawn strong criticism from Washington and European capitals.

It is "inevitable," says former Turkish diplomat Sinan Olgen, who now heads the Istanbul-based Edam Center for Studies, because any leader who has ruled Turkey in recent years has had to reassess his country's standing in a changing world, and he adds that Western countries are partly responsible for this acute nature of this shift. With the collapse of Ankara’s relationship with the United States and the “complete ineffectiveness” of the European Union as an alternative security partner to Ankara, the corollary of this was Turkey’s feeling that it should be more active to address its security concerns.

Ulgen believes that the tension caused by the amendment of Turkey's foreign policy has been exacerbated by the erosion of basic freedoms in the country over the past decade, which has caused concern among officials in the European Union and the United States. He says that this local background has made it "much more difficult" for Turkey to move smoothly on adjusting its international relations. Foreign policy has become increasingly intertwined with domestic politics, with Erdogan often seeking to antagonize Western countries to beg for popular support.

After the Turks once failed to obtain membership of the European Union, many Turkish officials now look to Europe with contempt, and question the seriousness of Brussels in accepting Turkey in this bloc. In parallel to European statements that Turkey's gas exploration in the waters near Cyprus was illegal, a senior Turkish official asked: "Why do they take the right in their hands to decide this?"

But although this position has had a wide resonance in Turkey, Erdogan is constrained by his country's continued dependence on the West as a trading partner and source of foreign investment. This was evident in 2018 when the country entered a financial crisis, after US President Donald Trump imposed economic sanctions to find a solution to the diplomatic dispute.

"Turkey diversifies its partners in security and defense, but not in the economy," says analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute, Alek Tigur, a Madrid-based research center, and adds, "If its relationship with the West is disturbed by its security interests or unilateral moves, it also risks To become economically weak. ”

Turkey's desire to look for greater influence in its neighborhood is not new. But her bold and growing pursuit of her goals has infuriated European and Arab leaders alike.