Gaudí Juan José Lahuerta Chair: "Gaudí is no longer from Barcelona"

Monuments in a pandemic A Gaudí without overcrowding

Essay 'The thought of Gaudí'

Controversy "La Sagrada Familia is a Mona de Pascua"

It is the size of an orange, albeit metallic and spiked (the percussionists that make it explode on contact).

It must have exploded 128 years ago at the Liceu,

in the middle of a representation of

Guillermo Tell: it

is the second Orsini bomb that a young anarchist threw into the stalls in the attack that shocked all of Barcelona and left 20 dead. Such was the shock that a few years later -with the terrorist executed with a vile club- Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926) sculpted that bomb in the Chapel of the Rosary of the Sagrada Familia: in

The Temptation of Man

, an unsuspecting worker receives the bomb, exaggeratedly large, directly from a demon-snake. Substituting the apple of Eve, the original sin is therefore violence, class struggle, social chaos. Although nothing seems further from the Gaudí universe than a bomb, that brilliant Orsini is one of the keys to understanding Gaudí and the Sagrada Familia, the temple to atone for the sins of the proletariat.

"

La Sagrada Familia is not the town's cathedral

or an architectural whim or genius. It is a building that goes beyond a building, with a great ideological charge. La Sagrada Familia, like all of Gaudí's work and even Barcelona itself , it has been trivialized to the extreme. It is a temple that imposes an image of the city, a temple to atone for the sins of society ", says

Juan José Lahuerta,

director of the Gaudí Chair at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC) and author of the indispensable essay

Antoni Gaudí. Fire and Ashes

(Tenov), where he dismantles the clichés and popular and idealized image of the architect. His theses materialize in the most ambitious -and critical- exhibition ever dedicated to the architect:

Gaudí

, which the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya (MNAC) inaugurates on Friday with 650 works and objects from more than 70 institutions. After its closure in March,

the exhibition will travel to the Musée d'Orsay and Gaudí will return to Paris,

the city that dedicated his first exhibition to him in 1910 (although it received mixed reviews: despite acknowledging its originality, for

French

good taste

this strange organic, almost visceral architecture was pure

bad taste

).

There is no Barcelona without Gaudí.

Symbol and souvenir,

Gaudí populated the city with iron dragons, lampposts with winged helmets, an aquatic floor of stars and seashells ... A fantasy, a delirium that he embodied in sinuous and undulating buildings that seemed impossible at the beginning of the 20th century. (At the time, the astonished Barcelonians came to compare La Pedrera with a parking lot for zeppelins and the towers of the Sagrada Familia with those of an industrial factory). But Gaudí's Barcelona was very far from that kind of Arcadia of vibrant colors and mythical animals. "

Gaudí is an icon stripped of all complexity

which has served to build the tourist image of a Barcelona of light and color, a kind of utopia of banalized happiness from the past.

But Gaudí's work arises from the conflict, he builds a symbolic system of an extremely turbulent city, "lahuerta laments.

Caricature of La Pedrera as a parking lot for zeppelins that appeared in 'L'Esquella de la Torratxa'.

One of the myths that the exhibition dismantles is that of Gaudí as an isolated and misunderstood genius, an enlightened mystic. "On the contrary, he

was the favorite architect of the upper bourgeoisie and of the Church.

And Gaudí knows perfectly the art and architecture of the time, although he interprets it in his own way," says Lahuerta, who places Gaudí in an international context , with parallels with what

William Morris did

in the midst of the apotheosis of the Arts & Crafts movement in the United Kingdom or the reinterpretation of the medieval legacy that

Viollet-le-Duc

had rehearsed in France.

Gaudí built a Barcelona that did not exist, literally: the medieval walls had collapsed a few decades ago and the new city stretched out on the perfect grid designed by

Ildefons Cerdà

towards the countryside, a void that appears on the maps of the time. From his first exercises as an architecture student (he was part of the second promotion of the degree), Gaudí has already designed this new Barcelona: a monumental fountain for the brand new Plaza de Catalunya, an elegant jetty with a restaurant, a spectacular auditorium for his university. "They are unrealized projects by a student, but they are closely linked to the spirit of the time, to a Barcelona that is beginning to become monumental and that is being built again," says Lahuerta.

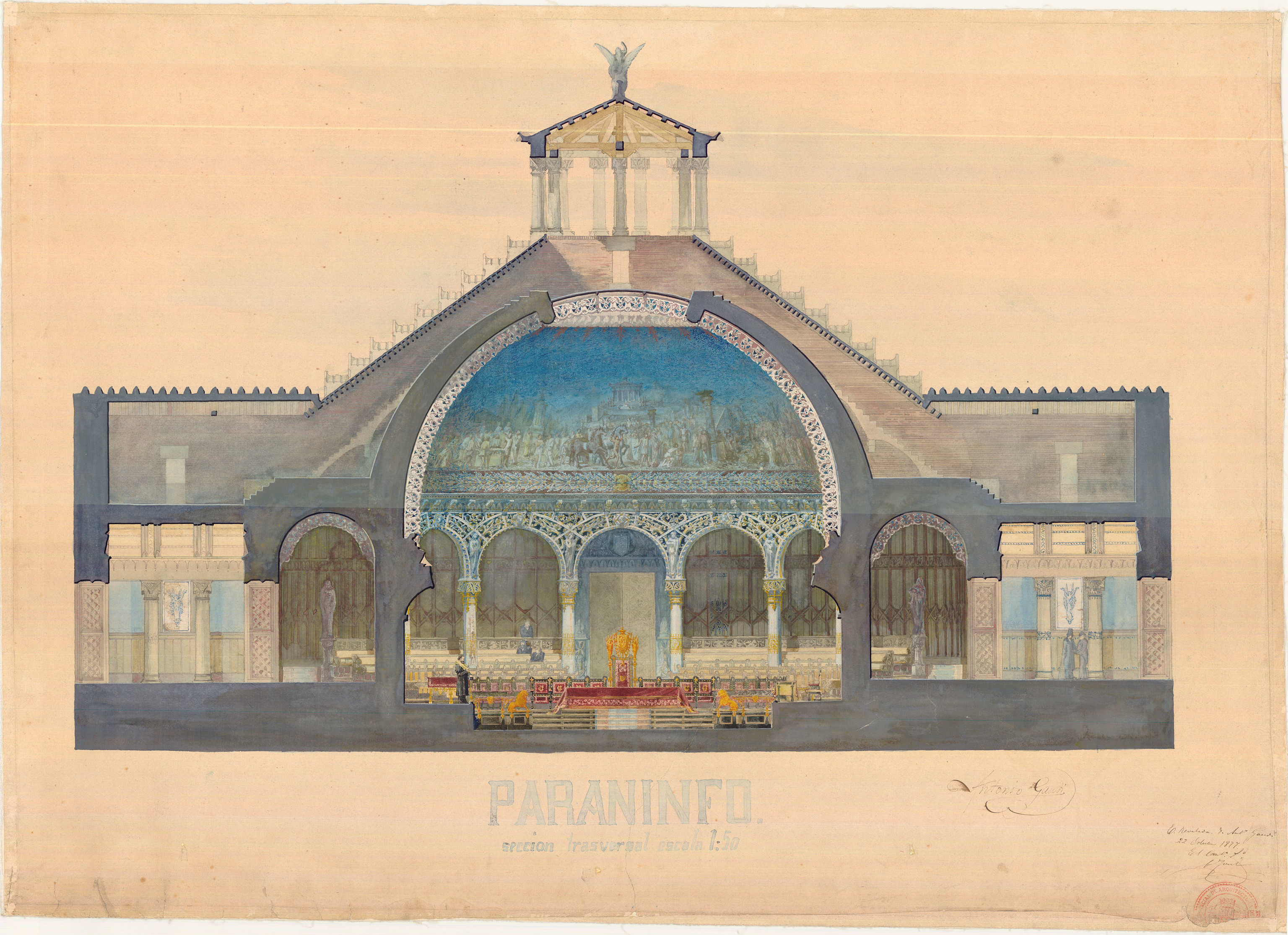

The paraninfo project that Gaudí designed in his last year of career.

Nor would there be Gaudí without a Catalan Medici:

the rich industrialist Eusebi Güell.

Under a completely aristocratic philosophy, Gaudí built for his patron

a palace in the heart of the old city

(Palau Güell),

a park

at the foot of the mountain (Park Güell, with an anti-urban ideology, wants to recover the archetypal Catalan landscape) and

a temple for its industrial colony

outside of Barcelona.

From

the Colònia Güell church,

almost a rehearsal for the Sagrada Familia, come the heavy undulating columns shown in the exhibition, 'fallen' to the ground as if they were the ruins of the temple of Zeus in Olympia.

Güell was followed by

the Batlló and the Milà, with their spectacular residences on Passeig de Gràcia.

From Casa Milà or Pedrera, the main floor lobby has been rebuilt, which in the 1960s had been dismantled and cut into pieces. Gaudí's furniture is not just furniture: it is conceived as an architecture that adapts to every corner. Even tiles and cobblestones are part of the architecture, such as the famous hexagonal tile with marine motifs that covers Paseo de Gràcia and that he had designed for La Pedrera, although he finally used it in Casa Batlló.

Nor would Gaudí be Gaudí without his colleague

Josep Maria Jujol,

his right-hand man, the author of the famous

trencadís

bench in

Park Güell or the forged balconies of La Pedrera.

Jujol was commissioned to bring a model of the Sagrada Familia with its polychrome façade to Paris.

Because Gaudí did not imagine a stone cathedral: like the Greek temples, the portico of the Sagrada Familia was to be covered in colors.

He also referred three monumental tapestries to Jujol to decorate the Llotja during the celebration of the Floral Games of 1907. Some tapestries that were folded and kept for more than a century.

Jujol's son donated them to the MNAC, where after several years one of them has been restored.

'The Cathedral of the Poor' by Joaquim Mir.

"In Catalonia, there was a deeply conservative ideological project that identifies the foundations of the homeland with its Christian origins. The great theorist was Bishop Torres i Bages, who was a model for Gaudí and the majority of Catalan artists. It is not that Gaudí perpetuates that conservative image, but is one of those that most contribute to it through the Sagrada Familia, "explains Lahuerta. Thus,

the Cathedral of the Poor

was built against the poor, something that the painter

Joaquim Mir

captured on a magnificent canvas: the Holy Family rising in the background while a miserable family begs in the foreground. Even more critical is

Isidre Nonell

in his drawing of an angel who visits the poorest of the poor, the lumpen who awaits divine glory.

In the section dedicated to the great expiatory temple, the period photographs show how the towers of the Sagrada Familia rose in a deserted lot and,

in 1909, next to the smoke columns of the Tragic Week

, when Barcelona rebelled against the call forced the reservists to fight in the unpopular war in Morocco. While the city burned, Gaudí continued working in his refuge-workshop: a somewhat gloomy space, in which sculptures, skeletons and plaster limbs were piled up. Some pieces of plaster -of the few that survived the fire of 1936- are shown in the exhibition: torsos and faces that Gaudí used for his sculptures. With a note of chill, the visitor discovers that the faces of some angels are based on the faces of deceased children.

Only after viewing the entire exhibition can one understand the two works that open it: an imposing bust of Barcelona as a royal Matron and a caricature of Barcelona as a fallen queen, with a rosary whose beads are Orsini bombs.

That was Gaudí's Barcelona: the aristocratic one that wanted to be a Midday Paris and the one with the conflict in the streets.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more

culture

Catalonia

art

Barcelona

Architecture

CultureThe Banksy effect: from street protest to commercial product

I'm sorry, Mr. Wes Anderson, a Spaniard has gotten into your eye

Comic Anaïs Nin, between writing and sex: "He was not a militant of anything, he only claimed his freedom"

See links of interest

La Palma direct

Last News

Holidays 2021

2022 business calendar

How to do

Home THE WORLD TODAY

How do you write why

Barça - CSKA Moscow