None of the Islamists who criticized the caliphate were calling for its abolition.

It became clear from their subsequent positions that they were not ready for such a step (social networking sites).

On the centenary of the abolition of the Islamic Caliphate, we still need to confront this event with greater contemplation and contemplation.

The absence of the Caliphate, and thus the Muslims’ lack of an initiative political center, is considered one of the most important factors that determined the reality of Muslims today.

The Caliphate was abolished within the borders of Turkey, but the consequences of this abolition extended to include all Muslims.

The abolition of the Caliphate had a shocking impact on the consciousness and awareness of the first generation of Islamists in the Republic.

After this event, the reality of the entire Islamic world can be described as a “post-Caliphate phase.”

For the first time in Islamic history, Muslims lacked a political entity that represents them, embodies their ideals, implements the plans of Islam, applies its provisions, and represents a political existence in the name of Islam.

This matter has two interrelated dimensions that must be addressed:

The first dimension: the absence of a jurisprudential precedent, as no similar situation was previously known in Islamic jurisprudence after the abolition of the Caliphate.

Muslims previously lived in situations where they were a minority with other peoples, but they felt belonging to another political entity that represented them and determined their status and position.

The second dimension: Evaluating the caliphate before its abolition. This dimension indicates an important fact, which is that the caliphate in the period before its abolition was far from meeting the expectations and needs of Muslims in the world.

It has become vulnerable to and available to the manipulations of the global system, and has lost its ability to defend the interests of Muslims.

There was also a feeling of dissatisfaction with the lack of application of the Shura principle in the caliphate, and its sometimes use as a tool to serve the interests of political rulers.

Many Islamic thinkers of the time, who later opposed the abolition of the caliphate, criticized the use of the position of caliphate.

From Saeed Nursi to Muhammad Hamdi Yazer, and from Muhammad Akif to Muhammad Atef Khoja al-Asqalibi, almost all Islamic thinkers and theologians criticized the people who occupied the position of caliph or the way the position of caliph was used and managed. The content of Sheikh Ali Abd al-Raziq’s treatise on the caliphate, which became part of From Islamic literature in Egypt, these criticisms are clearly evident.

It was not unlikely that Islamic intellectuals in the Ottoman Empire would share the option of abolishing the caliphate, even if it was not on the table. It is known that Omar Reza Dogrul, the son-in-law of Muhammad Akif Arsoy, translated this thesis into Turkish in 1927. In this thesis, Abd al-Razzaq asserted that the caliphate A political, not a religious, institution.

He explained that its transfer to the sultans of the Ottoman Empire did not grant them religious authority.

He also emphasized that Muslims may demonstrate their political presence through other institutions under different circumstances.

For people to submit to a style of clothing that did not symbolically express what they believed in, and represented a body politic in which they did not believe, was seen as sufficient at first.

When this work was published, the Caliphate in Turkey had not been completely abolished, but all its functions and characteristics had been incorporated into the moral personality of the Turkish Parliament. This shows that if there was sufficient confidence in the cadres of the Republic, such a solution was already on the horizon. politics of Islamic thinkers at that time.

Even the long speech that Sayyid Bey gave in the Turkish Parliament during the discussions about abolishing the Caliphate was based on the same Islamic criticism of the Caliphate. In addition to this, the most important source from which Mustafa Kemal drew his arguments in speeches he delivered on various occasions to justify the abolition of the Caliphate, in which he cited historical facts about the Caliphate in Islam was derived from the same critical accumulation directed against the Caliphate.

However, none of the Islamists who criticized the caliphate were calling for its abolition.

It became clear from their subsequent positions that they were not ready for such a step.

First and foremost, the abolition of the Caliphate created a large legal and jurisprudential vacuum that made the application of Islamic jurisprudence impossible.

Islamic jurisprudence did not adequately address how to implement the provisions of Islam or even how to exercise Islamic presence in the absence of an institution leading the Islamic world.

The teachings of the Qur’an assumed the existence of Muslims in a political organization and addressed them as such.

In the absence of this organization or entity, the vast majority of Sharia rulings become null and void.

This includes a wide range of applications, from the management of day-to-day civil affairs to wider social systems.

In the absence of this entity as well, the addressee in many Qur’anic verses does not exist.

It can be said that an individual's belonging to a state that expresses his religious values is a basic condition for living a Muslim life.

The state that implemented God's laws gave Muslims a strong sense of belonging and interdependence, as they were viewed as one body that was obeyed to achieve common goals.

This state - which is usually associated with Sunni Islam - formed the political and intellectual background for Islamists in Turkey.

Therefore, the new situation that arose after the abolition of the Caliphate can be described as the transformation of Muslims into members without a body... after the abolition of the old political body that Islam revived, and its replacement with a new social and political body, governed by the same members (the masses of the subjects).

The new body was claiming the right to human resources and to control the institutions that gave life to the old body.

One of the most important reasons for insisting on changing the external appearance was the attempt to dress individuals who considered themselves part of the old political spirit in new clothes that fit the new political spirit in order to make them a part of it.

Of course, this form of physical appropriation had a modernity dimension.

For people to submit to a style of clothing that did not symbolically express what they believed in, and represented a body politic in which they did not believe, was seen as sufficient at first.

It appeared as if modernity did not represent a challenge to faith and belief, as long as people adhered to these (outward) actions.

But the picture did not appear that way to the people who faced the reality of the absence of the Caliphate. Integration between what you believe in and what you do seemed important, and the “Hat Revolution” that they faced represented a real definition of faith as well as action, with its suggestions for revitalizing alternative political bodies to Islam, and so it turned The first reactions to the absent caliphate turned into a real tragedy.

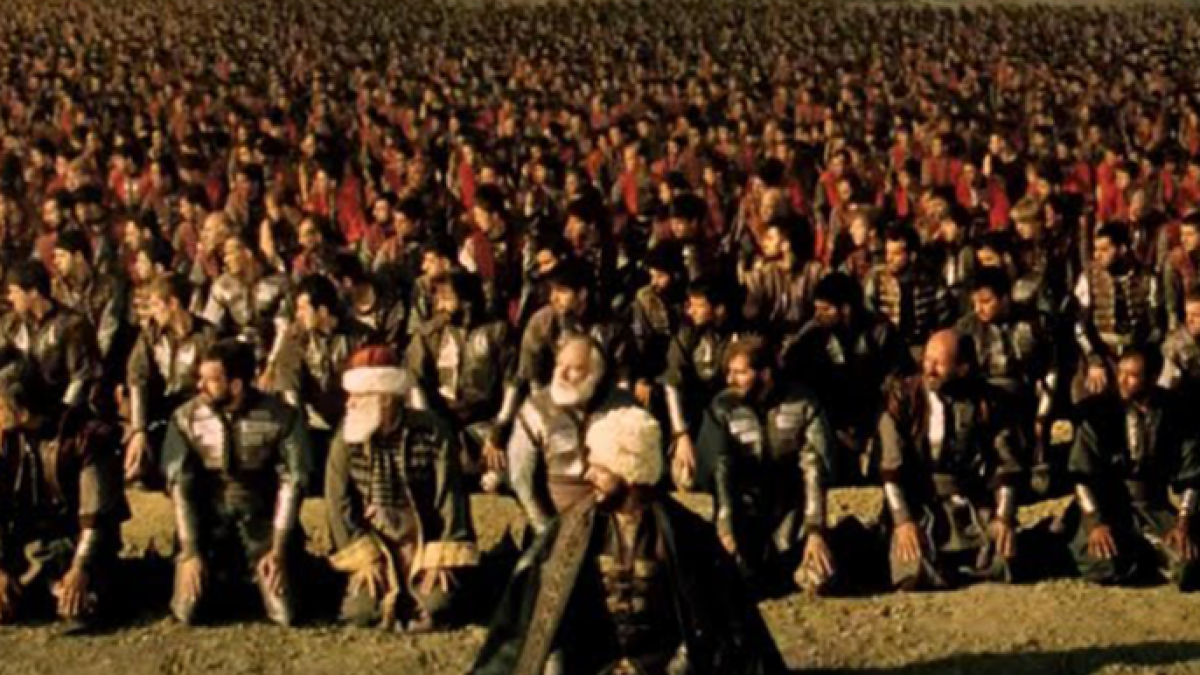

Therefore, the process of abolishing the Caliphate in general began with a serious consciousness shock for Muslims in many parts of the world, especially for Turkish Muslims.

After the first effects of this shock, Islamic thinkers - who tried to understand what was happening - did not accept this situation as a sustainable condition for Muslims.

Under the new circumstances, Islamic life was deprived of all types of relationships.

The jurisprudence of “temporary situations” became one of the most prominent literatures of early Islamic texts in the post-Caliphate period.

As this temporary situation (or the absence of the Caliphate) continued, different reactions, results, and aspirations crystallized among the Islamists.

This is an aspect that deserves to be focused and thought about carefully in order to understand the conditions of Muslims today.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Al Jazeera.