In the few times that dialogue was available in prison (2015-2019) between some Islamist leaders, the experience of the Renaissance was present as an example of success that the Brotherhood of Egypt should have followed suit on the one hand:

The ability to build broad cross-ideological political alliances

Separating the advocacy from the political

Political flexibility or pragmatism

Intellectual decisiveness in the relationship with issues of democracy, modernity, and the relationship with the nation state. The Islamists in the Maghreb are an exception to the Islamic situation in the Levant.

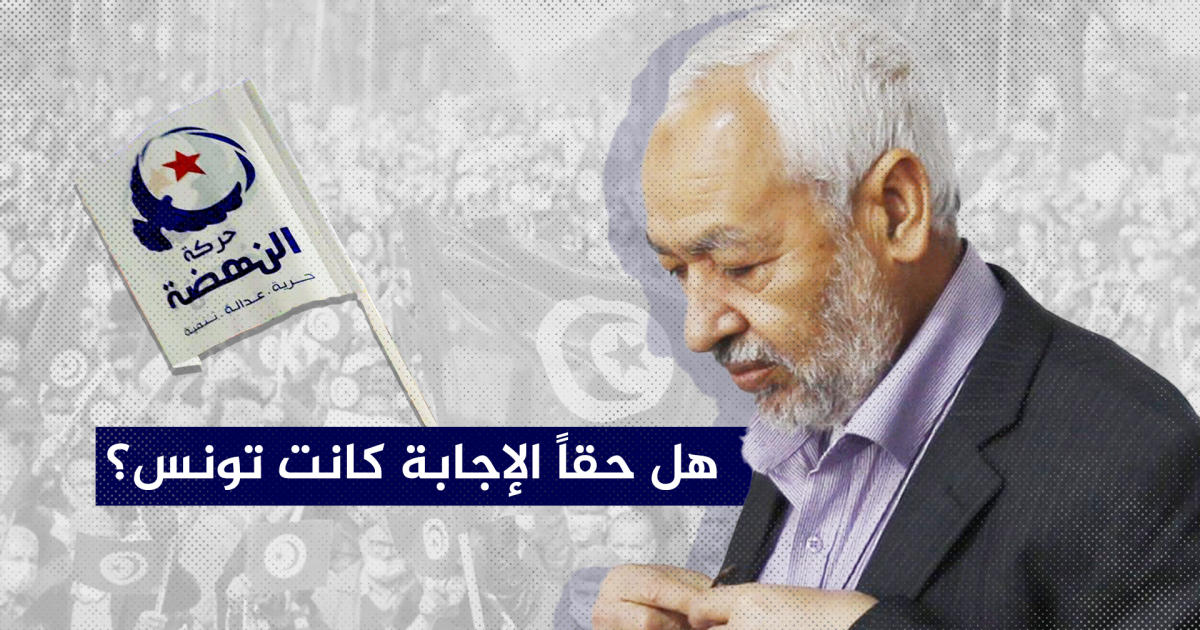

Hence the importance of pausing for a long time in front of the implications that the current Tunisian crisis poses to Islamists in the region. Although it reveals the depth of the crisis they are going through in the era of the Arab Spring, however, an in-depth reading of this crisis would help reposition Islamism in the political sphere.

Islamists in power - as in the opposition - behave like other political actors when they are moved by their realizations of their self-interests that they want to achieve, and they build their alliances not according to ideological foundations, but the competition between them was more intense than their competition with others.

Approach to the crisis

4 determinants, from my point of view, we must deal with what is happening in Tunisia:

First: The end of Islamic exceptionalism

The main impression he made after completing the follow-up to the performance of the political Islamists in the Arab Spring - especially in its second wave 2019, and some of their parties are now in power or supportive of it - is the normalization of these movements with the Arab reality with all the negative and positive connotations that this word carries, which With him, it can be said that the “Islamic exceptionalism” has ended, with which its followers and opponents tried to stigmatize it alike, even if the motives differed between them. As for the analysts and researchers, in their relationship to democracy, a number of conditions must be met to ensure the success of their integration into the existing political system, as if this is not required by other political forces.

The Islamists in power - as in the opposition - behave like other political actors when they are motivated by their realizations of their self-interests that they want to achieve, and they build their alliances not according to ideological foundations, but the competition between them was more intense than their competition with others, and most importantly, the Arab Spring in its two waves proved beyond any doubt They do not have a different project for power, but rather behave like any Arab ruler: the political opportunism that characterized the experience and practice of many of them in and outside the government, the fluctuations of their positions and alliances, the multiplicity of their transitions from one trench to another, and the spread of manifestations of corruption in some of their circles. Above the heads of its leaders is the "aura of holiness".

The last ten years have proven that the project in its political structure is too inconsistent to qualify it to be a government project that presents an alternative to the crisis Arab state. On the contrary, the experience of Islamists in politics has shown that the project carried by their movements exacerbates reality, as it is largely separate from the requirements of reality and its dictates. It tends mostly to slogans that are not supported by clear programs and projects for the government, and most importantly, the narrative of these movements on which their legitimacy was based has ended, as I can, or at the very least became questionable by their followers and supporters before their competitors and critics.

The narrative of Islamic movements in the twentieth century was based on four pillars: the comprehensiveness of Islam, that is, the attachment of the Islamic reference to all matters of life, the centrality of authority as an essential tool for the application of Sharia, the rejection of the national state and its transcendence, but rather the attempt to rebuild the nation itself on the basis of a new identity and legitimacy using the sacred comprehensive organization whose sanctity derives from his mission.

We will not discuss the components of this narrative and what it ended and what are the elements of its failure and success, but most importantly, the response of the Renaissance over the past decade (the decade of the Arab Spring) was an attempt to depart from this narrative, but the problem with this is that the response was unable to present a new narrative different from the narrative twentieth century and able to realize the nature of the Arab uprising model.

That model embodied by the movement of the masses in the streets, and then it fell into the traps of the problems imposed by the narrative of the twentieth century. The current problems are more extensive than this single organizational formation, and here contemporary experiences provide us with the form of a social movement that combines a common vision and goals with multiple organizational forms, and the experience of the Arab Spring provides us with the form of social movements and network organizations as a model.

The conclusion of this specifier is that the masses - whether in Egypt 6/30 (2013), or July 25 (2021) - have viewed the Islamic parties as a political party like the rest of the other parties, and were able to separate the religious component in the discourse of these movements from their political practices. .

Second: The narrative of the Arab Spring

In my book on the Arab Spring, I argued and still argue that there is a new narrative of the Arab Spring uprisings that announces the end of the 20th century formulas, at the heart of which is the post-independence state and Islamic and secular political movements that were based on totalitarian ideologies, and that we are in the process of new formulas that have not yet been institutionalized, as protest has prevailed. And it lacked the crystallization of its nurturing and motivating social base.

The narrative of the Arab uprisings is a search for a new social contract by which the nation-state is rebuilt with new elites. This contract is based on three components: freedom/democracy, social justice/equitable distribution of wealth and opportunities, and liberation of the national will from regional and international domination, and at the heart of it is the question of Palestine as well as Confirmed by the Jerusalem Intifada 2021

The historical reading of the Arab Spring uprisings is that we are facing a reconfiguration of all history in the region. We are facing a historical watershed. The old led to the explosion and is no longer able to provide responses to the challenges of society and the state, but the new has not yet crystallized, and this is our historical mission, I think, and the moment is not Empty as some think, it is filled with lots and lots of what is pouring into the future, and to the extent that Islamists or others are able to capture the ingredients of this moment, the more they will regain their presence and their momentum, which has greatly diminished.

I am aware that the projects of the nomadic past were not mere formulations and passing phrases carried by the power of authority in the sense that Foucault presents. Society and its members have a perception of the self and the other that expresses itself in laws, legislation, constitution and production relations.

The narrative of the Arab uprisings is a search for a new social contract by which the nation-state is rebuilt with new elites. This contract is based on three components: freedom/democracy, social justice/equitable distribution of wealth and opportunities, and liberation of the national will from regional and international domination, and at the heart of it is the question of Palestine as well as Confirmed by the Jerusalem Intifada 2021.

This dream is almost agreed upon by the middle and lower classes and some segments of the upper middle class, but its driving force is new generations of young people with an overwhelming female presence.

Here the question becomes: To what extent are the Islamists able to embody this narrative in the reality of the people through political programs of government, especially since these masses have been granted, through the election boxes, a mandate for them to express their legitimate aspirations for a dignified life, but they have failed them?

Third: Tunisia and the crises of democratic transition

There is always in the Western view that has infiltrated sectors of our researchers and elites that this region is exceptional, especially in its relationship to modernity and democracy, and this was taken to give priority to cultural / value elements over structural and structural factors in the analysis, and the Tunisia model was considered important because it helped dispel the myth that says Democracy was not possible in the Arab world when the surrounding countries descended into civil war or descended into authoritarian rule.

Tunisia held free and fair national and local elections, adopted a liberal democratic constitution, witnessed a peaceful transfer of power, and agreed on building the constitution and political institutions through the extended dialogue that was used to address the crises of transitional periods.

But the problem is that the Tunisian experience has always been presented as a multidimensional exception, as it is an exception to the Arab Spring, and the Islamists in it are an exception, its people and elite are an exception to the region, and its educated middle class open to the West is an exception, and thus exceptionalism ruled the experience, and hence the shock was greater, but it is certain that Comparative experiences of the democratic transition show us that its path does not follow a straight, ascending line, but rather takes turns and curves, and Tunisia is no exception to this, even though it represented an important laboratory for many of the issues and issues raised by this transformation and the nature of the transition in the Arab region.

Fourth: Secular Islamic polarization

The basic thesis that I present is that the secular Islamic conflict in the Arab Spring was and still is of a political nature in which its multiple parties test the balance of power between them in light of mutual misgivings and fears, uncertainty in the outcome of the political process, and a strong mixture of religious feelings with political interests, and that what appeared from the conflict Regarding the position of Sharia in the constitution, it was - in my view - nothing but a struggle for influence and a search for political support and a use of mobilization and mobilization for supporters. Sharia was one of the tools of the struggle, not its essence.

The second wave has clearly highlighted this fact, because we are confronted with actors whose political behavior is controlled more than ideology. In the first wave, the political Islam movements were in the opposition that struggled against the existing rulers and regimes.

In the second wave, in 3 of the four cases in which the protests took place (Lebanon, Sudan and Iraq) and in Tunisia, we now see the Islamists either as rulers or supporters of the existing regime, and this creates a completely different dynamic for political Islam. In some countries, Islamist factions mobilized in opposition against other sections. of Islamists in power, and this can be interpreted as an expression of the deepening division within Islamic movements in the Arab world or as an opportunity for countless Islamists to clarify their divergent positions on major political issues, as it is related to pluralism that has become a reality in all Arab political currents.

The experience of the Arab Spring shows us that secular Islamic polarization was used to cover up other types of it that were more important, such as the conflict between street politics and institution building, or the struggle between the regional/local and between the central, the struggle between the revolutionary and the reformist, and last but not least, between social/economic and political demands. .

But the Tunisian case offers us two important lessons in this regard: The first, unlike the Egyptian case, is the presence of a significant segment of its elite and civil institutions that did not support the “coup” of Qais Saeed, and he has real fears and concerns regarding the democratic path in Tunisia, and this does not necessarily mean supporting Ennahda’s position. Rather, he bears great responsibility for the situation.

On the other hand, the experience of the Arab Spring - not only in Tunisia but in the entire Arab region - has shown that there is a secular elite whose components are varied between liberal, nationalist and leftist, bent on sacrifice or bartering the elimination of all Islamists for democracy, and it sees in these crises - which they can be exposed to. Transitional periods - an opportunity to make it happen.

This position puts these elites in front of their historical predicament. This formula also, i.e. alliance with authoritarian regimes to eliminate Islamism in the political sphere, has proven to be a failure. Democracy, social justice and modernity as they were targeting.

In other words, the lesson that these elites should learn from the decade of the Arab Spring is that the formula that all Arab regimes put forward in clear contradiction to the narrative of the Arab Spring, from which the Arab peoples gained little from improving their lives, led to civil wars and mass exodus...etc, and became The question about the future of stability in the long term is being raised among experts and specialists in the region now.