« A week without drugs and Rio de Janeiro stops . There would be no doctors, no bus drivers, no lawyers, no police, no sweepers, nothing. Everyone with a monazo of fright. Cocaine, Diazepam, LSD, ecstasy, crack, marijuana, Nolotil, whatever, brother. The drug is the fuel of the city ».

Geovani Martins, who is a 28-year-old Brazilian from Rio, does not say so, but a character from his book The Sun in the Head (Alfaguara), which groups 13 stories about the city. Martins knows what he writes. Of drugs and favelas. He grew up in one of them and lives there . It is not seen elsewhere.

Geovani Martins wears a leather jacket, a tracksuit from the Flamengo football team, a Flamengo shirt and an open hair like a palm tree during these days of promotion in Madrid, Barcelona, Lisbon, Paris and Milan. Who was going to tell him or his family a few years ago. This shy boy learned to understand the world by writing the stories his family and friends told him. "Writing palliated my loneliness, conjugates with my anguish and I earn money," he says. His mother taught him to read when he was four years old and his grandmother whispered stories. Others already knew them for himself, as when in 2011 the Pacifying Police Unit entered the Rocinha favela with all that it supposed. This is the theme of the novel he now writes.

«At 17 I became independent from my family. I started smoking with 15 years. I smoked pot, drank LSD, I had a history with cocaine, with alcohol ... But crack , no . I like soft drugs, I prefer a trip, imaginative drugs, ”he says. «I smoke to work, to read, to live. Mary calms me when I'm nervous writing. I worked everything. I was three or four days in one thing and then left because I just wanted to have money to write.

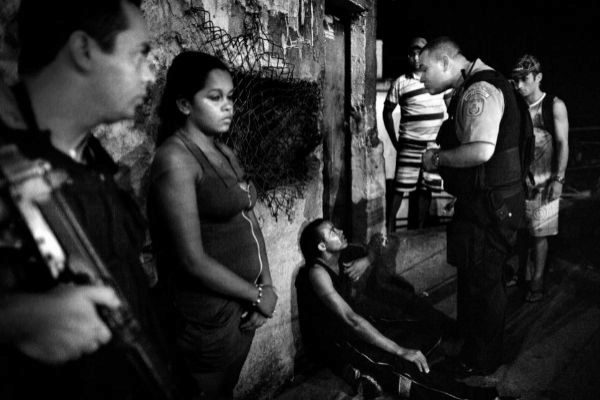

He wrote a little for fun, a little for showing it to his friends. I read aloud what everyone saw; In addition to drugs and shortages, violence. " I have grown up in the midst of violence , it was something natural and that is why I pretended that violence was seen in the book as something natural." As City of God (2002), that film by Fernando Meirelles. Sneaks, girls, baths in the sea, flip flops and raids of the police who keep the drugs and money.

The Russian Roulette story describes how "without being unfazed by the sun that was giving them in the head they fought for the best place to watch the porn soap opera that Mingau had found in his house when he rummaged between the things of his missing cousin." In that story, a 10-year-old boy denied by his friends shows them a 38-caliber revolver from his father to assert himself. «Paulo loaded and unloaded the revolver several times pretending he was training for the war ... He pressed the cold tip of the barrel against his chest and then went down until he reached the navel. Then he tried to imagine what it would be like to get shot right there.

Paulo is tired of not standing out in soccer pachangas, or with marbles, or with the kite; Not because it was funny. «I'm going to tell you one thing, but it's a secret. My father has already killed a person with this weapon ».

There are less disembodied stories, such as The Butterfly Case : a sleeping grandmother in front of the soap opera at seven o'clock, a butterfly swims slowly in the oil of a casserole and "if you get butterfly dust in one eye you become blind."

Or the blind man : a blind orphan (who "has never seen the sea, nor a weapon, nor a woman in a bikini") makes a living by telling his life on buses to snort the calderilla they give him as alms at night .

"I shape many issues to give color to the city," says this follower of players like Salah, Casemiro, Coutinho and Zico and Adriano in the past. «The book is a mosaic of different realities. Writing gives me pleasure and pain . It's like what Lawrence Olivier said in Confessions of an actor : writing would be like the one who is hitting his head against a wall and asking him why he does it, and he replies: 'Because it's great when I stop'.

His writing was surely born when at age 11 he switched to another favela corseted between "two rich neighborhoods." Then he realized the " social tension , of a new world that traumatized me, in which I was not welcome."

Something similar appears in Finally Friday , in which a kid is robbed by four policemen. “In Brazil,” he says dejectedly, “ only the rich do not fear the Police . I grew up afraid of the police and had many problems with them. Problems happen but blackmail, arrogance, intimidation ... I still fear the police ».

On Bolsonaro , Martins does not doubt: «It is worse than it seemed, which already seemed bad. It reflects the worst of Brazilian society, which has always tried to hide what it is: racist, homophobic, macho, with prejudices.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more- Brazil

- literature

- Violence

- culture

- Drugs

- Jair Bolsonaro

The Sphere of PaperPedro Mairal: "Literature is the hidden side of social networks"

Culture Historian Xosé Manuel Núñez Seixas, National Essay Prize

The Paper Sphere Rodrigo Fresán: "I'm amazed that everyone thinks their life is of interest"