In the situation of those rescued by the Open Arms ship, and in general of the migrants eager to reach Europe that are made to the sea from the coast of Libya, two types of legal norms have a very different origin and purpose .

On the one hand, there is the uniform maritime legislation of international origin (mainly the Rescue Conventions of 1910/1989 and the Search and Rescue Agreement) that establish the obligation of the captain of any ship to provide assistance to the shipwrecked or endangered persons it finds at sea, rescuing them and driving them to a safe place or port. It is the norm that the rescuers of the NGO have invoked (the "law of the sea", they say) to demand that they be allowed access to a Mediterranean European port and disembark the migrants there. Although in purity, although we do not want to make a point issue, the concept of safe port in Maritime Law would not exclude Libyan ports as stated somewhat a priori, except for Tunisians.

But, on the other hand, there is the national legislation referring to such a sensitive issue as immigration, in which the European states (for many variants that exist among them) maintain in principle their sovereignty as a capacity to control the income of migrants by their borders, based on a general principle: irregular or unauthorized immigration must be avoided. A principle that can contradict the ultimate values of cosmopolitanism that is at the base of liberal democracy (which is why it is so unfriendly) but that cannot be abandoned without more pain than jeopardizing the survival of the state framework that makes democracy itself possible day by day. Relentless reality limits the impeccable principle, Rafael del Águila explained it very well.

Well, it is quite clear that when migrants from Libya, or rather the organized networks that control them, are thrown into the sea in vessels lacking the slightest navigability conditions to transport people safely to European ports, What they are doing is deliberately placing them in the immediate potential shipwrecked situation. These are not shipwrecks consequential to a maritime accident , which are those in which the Uniform Agreement thinks, but rather "shipwrecked of convenience." And I explain myself: maritime navigation has been since ancient times a space environment conducive to the phenomena of interested adoption of fictitious legal appearances, such as the so-called "flags of convenience": insignificant countries that granted and granted their flag to vessel owners interested in escape the tax, labor and safety regulations in force in the country where the real substantial relationship with the ship and its exploitation lies. For the same thing happens with migrants, no matter how much they do it out of desperation and not due to surplus value: they formally become shipwrecked to ensure that, thanks to that condition, and once saved, they are allowed to enter Europe bypassing the prohibition in this regard.

Thus, in the end, what we attend in Mediterranean waters is one of the most obvious cases of law fraud in the legal technical sense of the expression (art. 6-4º Civil Code) that can be imagined: well, intentionally resorted to create the appearances of a factual event regulated in a certain way in a special law ... to escape the inexorable application of the general law that really corresponds to that underlying factual situation; which is one of emigration and that is prohibitive. Bypass one law based on another. The Civil Code, and common sense, say that such a trick cannot be worth it.

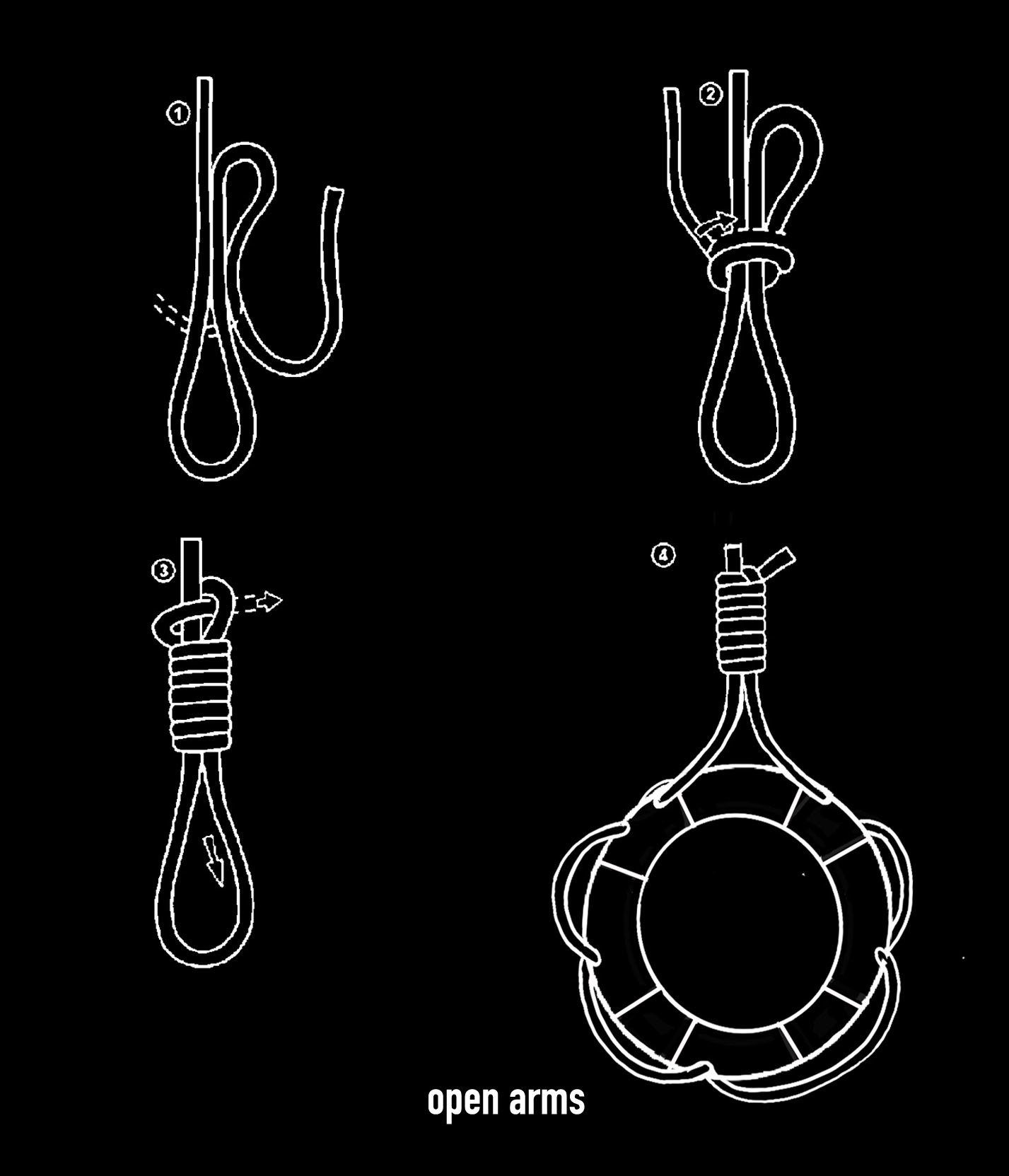

Does this mean that the castaways found (wanted?) By the Open Arms should have been abandoned to their fate? Obviously not, human life is well above such consideration, and the false shipwrecked of the Open Arms should be helped. There is no doubt about that, as it has happily happened at the end of that awkward and emotional pulse among many different actors that we have attended. But what does authorize, in our opinion, this situation of widespread law fraud is that the affected States intervene to stop it and to prevent the actions of individuals who are enthusiastic and well-intentioned dissants from only aggravating the problem. The rescue becomes a public matter reserved to the Administration when relevant public interest aspects are at stake, such as the environment. And as it should be in case of control of irregular migrants.

Intervening is what the Spanish government did months ago: that is why the Open Arms was dispatched by the Maritime Authority on the condition that it not be used to rescue shipwrecked people, even less in Libyan waters. Not on a whim, but on the well-founded suspicion that their presence in those waters would encourage potential migrants to endanger themselves in the hope of being rescued. But their shipowners decided on their own that complying with the law can be very debatable when nothing less than suffering humanity is placed on the other side of the balance, and they broke the ban. This does not prevent them from later crying for compliance with another law (although it seems that they do not want to return to Spanish port with their ship, suspecting the sanction that awaits them). It is a phenomenon to which we are accustomed in Spain, that of the ease with which it is admitted argumentatively that laws can be broken if one finds a superior value to knock it down: democracy, in a well-known case, humanity now.

The case ends and the unleashed feelings of sympathy rest. But what will remain is that there will be shipwrecked of convenience (and some will die for it) as long as they have confirmed hope that there will be rescuers waiting for them out there. An unsustainable deadly loop that must be cut somewhere.

Jm Ruiz Soroa is a senior professor (jub) of Maritime Law at the UPV.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more- Open arms

- Europe

- Libya

- Spain

- Refugees

EditorialIrresponsibility with the Open Arms

EditorialJustice for the Open Arms

Thoroughly Open Arms Lessons