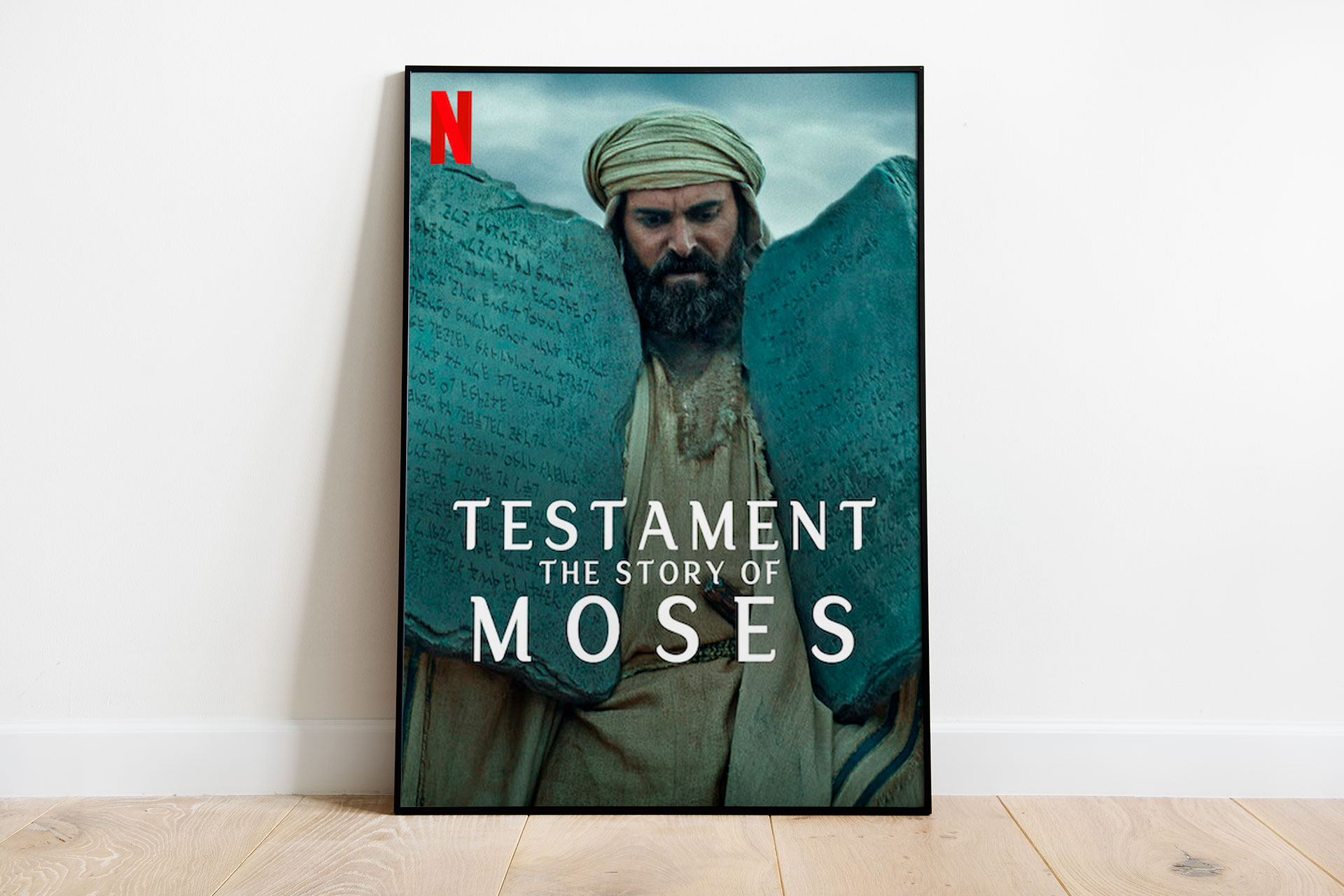

The promotional poster for the documentary “The Covenant: The Story of Moses,” which is shown on Netflix (Al Jazeera)

The documentary “Testament: The Story of Moses,” by British director and writer Benjamin Ross, has been among the most watched works in 55 countries around the world since it began showing on Netflix on March 27.

The film, which is divided into 3 parts, presents the events of the story of God’s Prophet Moses through a biblical vision. It also depicts the Hebrews, victims of the Pharaoh’s enslavement for about 400 years until Moses came to liberate them.

“The Covenant: The Story of Moses” joined hundreds of films and series in which filmmakers participated in presenting the stories of the prophets, especially the Prophet Moses, starting with the American director Cecil de Mille, who presented the film “Ten Commandments” twice, the first as a silent film in 1923. Then he carried it out as a speaker in 1956. As for the last film produced about the Prophet of God Moses, it was the film “Exodus: Gods and Kings,” which was released in 2014 by British director Ridley Scott.

“The Covenant: The Story of Moses” reviews the life of the Prophet of God, starting with childhood in the cradle, and continuing through his life in the Pharaonic court, then the killing incident that forced him to flee, after which the journey of prophecy, the assignment of the message, and the liberation of his people began.

The work combines the dramatic narrative of the Old Testament story with modern scholarly observations and interpretations of the story, which begins in the Book of Exodus and ends in the Book of Deuteronomy, and interviews with authors, such as Jonathan Kirsch and Dr. Celine Abraham, rabbis such as Rachel Adelman, and priests such as Tom Kang, provide interpretations Interesting story events.

The specialists reconsider the translations of ancient texts and their meanings. They also shed light on how Pharaoh’s woman challenged him as an authority and as a man, and they discuss the biblical narratives about divine revenge contained in Jewish texts.

Desert and palace

The novel appears to be a “voice” completely separate from the novel “an image.” While the narrators tell the story of the Prophet Moses and provide analyzes and interpretations related to the faith of each of them, the dramatic scenes tell another story about the revolution of a group of primitive, uncivilized people.

These Hebrews had been kidnapped by the Pharaoh and enslaved, and they appear in the scenes lacking everything related to “civilization.” Loud voices, tension, and fistfights are prevalent among them despite their strong emotions.

As for the Pharaonic palace, we find the exact opposite, with elegance, a calm voice, and mutual respect, except in one scene when the Pharaoh gets angry and slaps his minister, Haman.

The visual story here takes an anti-Hebrew stance, and supports the Pharaoh, whose every scene was photographed with great care. The camera is either from the lower level to show the enormous and majestic Pharaoh, or parallel to him to keep him in a state of constant presence.

This may be justified by a life of slavery and the slave’s inability to control his will, but it will become an excuse worse than a sin, because these slaves liberated themselves by going out, and by freeing their souls by faith.

mistakes

In contrast to everything that was presented before, director and writer Benjamin Ross clearly records at the beginning of his work that the story being told relied on details drawn from multiple religions, in the words of which she said, “This series is an exploratory vision of the story of Moses and the Exodus based on the integration of the opinions of religious scholars and historians from “Their contributions from different cultures and religions are intended to enrich the narrative, but it should not be considered an agreed-upon narrative.”

The director was honest about the "direct narration" through the work's guests or commentators who took on a very small narrative part and a large analysis part, but the dramatic scenes that were the real hero of the work and the most prominent thing in it, contained only the Biblical narration, and specifically, it relied on a narration. Exodus and Deuteronomy.

The maker of the documentary - which aims to retell a historical story - needs historical scholars to tell the story, but he used two Egyptian archaeologists, then rabbis and priests to be representatives of Christianity and Judaism, and thus sent a message summarizing that the Torah is the book of history and religion together, and this is what was achieved. Also, by transforming the texts of the “Book of Exodus” from the Torah into dramatic scenes.

The use of a single source resulted in a number of errors, including that the one who adopted Moses, peace be upon him, when the waters of the Nile carried him as an infant was the sister of the ruling Pharaoh, in contrast to the Islamic narrative, which says that the one who picked him up was “Pharaoh’s wife,” meaning his wife, namely Mrs. Asiya bint Muzahim.

The makers of “The Covenant: The Story of Moses” chose Ramesses II as “Pharaoh Moses,” which is inaccurate for two reasons: The first is that the mummified body of Ramesses II, which is preserved in the largest museum in Egypt, testifies that he did not die by drowning as in the story of the Prophet Moses. The second is that there is nothing This is proven historically or in terms of artifacts or physical evidence that archaeologists may find.

Benjamin Ross used the Israeli actor Avi Azoulay to embody the role of the Prophet Moses, and the German of Turkish origin, Muhammad Qurtulush, to embody the role of the Pharaoh. In the scenes that brought them together, the two actors engaged in a real competition in breaking the rhythm of movement for the character that each of them embodies, despite the clear efforts of the director, whose impact was evident on Lazuri. To show the Prophet Moses as a nervous, tense person, who is characterized by haste and then returning to correct his mistakes, but Lazuri embodied his role with eyes that practiced hypnosis instead of a charismatic effect that does not require constant and exaggerated staring, which is what Qortulush did with the same degree of exaggeration.

Israeli actress Raymond Amsalem played the role of Miriam, the sister of Aaron and Moses, well, and the work was based on the three characters as the heroes of the story of the Hebrews’ exodus from Egypt.

Hype

Benjamin Ross exaggerated the simplification of the story and concepts contained in the three parts of the work, so that its final form was closer to works produced to teach students, because Netflix’s teenage audience is the target of the work that seeks to educate and entertain them, and to gain their sympathy.

The series “The Covenant: The Story of Moses,” which mixes documentary with drama (docudrama), gained momentum from audiences around the world, as within two days of its start it topped the list of the most watched works in 55 countries in the world, but the most important question remained on the minds of viewers: What is new? ?

Although the work took the appearance of an investigative television report, it did not bring anything new, whether at the level of details that it could have revealed, or at the level of vision, as it remained as it was presented from the beginning. The conflict between Moses and the Pharaoh was not between two people, as much as it was between a religion. Moses and the religion of Pharaoh. More precisely, Moses brought monotheism in contrast to the polytheism of the Pharaoh.

Source: Al Jazeera