Energy prices, bottlenecks in the production chain after the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

These are the Riksbank's explanations for the fact that the inflation rate is sky high above the long-term target of two percent.

But critics believe that the Riksbank itself made the problems worse by putting the brakes on far too late and out of fire on the inflationary bonfire with low interest rates and "newly printed" money.

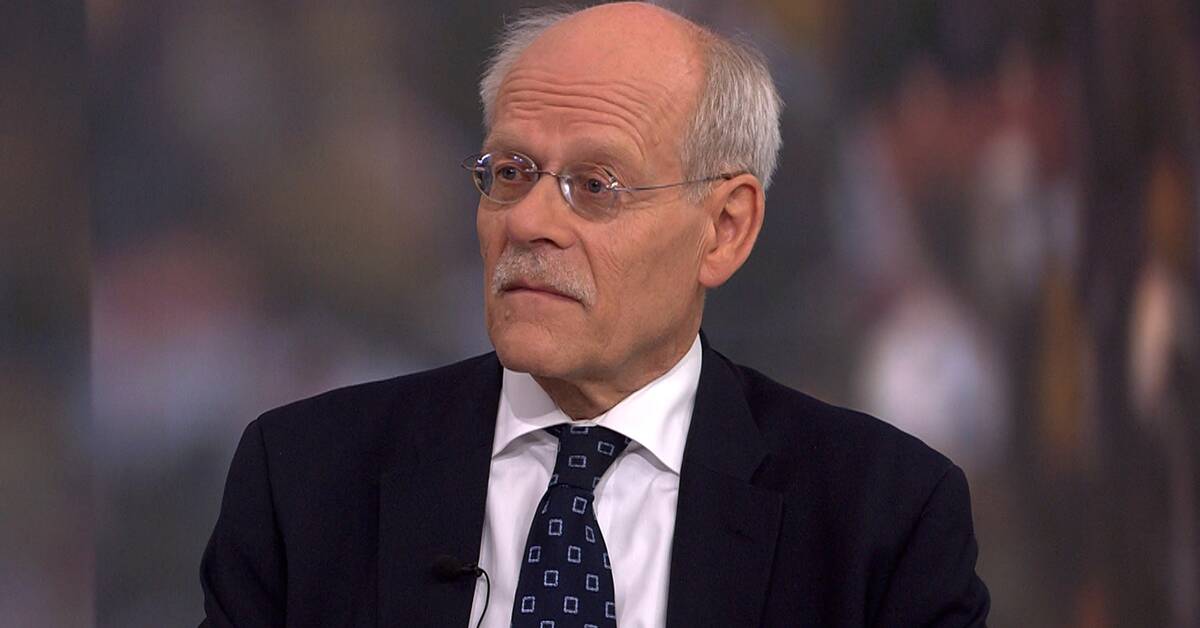

- The pandemic and the war in Ukraine show that it is an uncertain world where things happen that cannot be predicted, says Stefan Ingves.

As recently as last September, the Riksbank predicted that inflation was about to fall back and that monetary policy needed to remain expansionary to keep the economy going.

In addition, that the zero interest rate situation would last until 2024. Forecasts that today appear to be misleading, to say the least.

- They are obviously wrong, but then you have to remember that Sweden has had low interest rates and low inflation for a very long time.

We made the assumption that "it will be about as it usually is" - and that is not an unreasonable assumption.

But now the world became completely different, and we have to deal with that to the best of our ability, says Stefan Ingves.

- It would be worse to sit back and pretend the world hasn't changed.

Hear more from Stefan Ingves in the clip.