Occupied Jerusalem

- "Bring the newspaper to read it. We will see who took over our country. When our country is divided into two parts, a Jordanian section and an Israeli section.. It is Beit Safafa. End your friends, and the loss of the Jews stops at your door."

This folk song replaced the other popular wedding songs in the village of Beit Safafa, south of Jerusalem, after dividing the village with a border strip separating the children and homes of the same family into Israeli and Jordanian parts.

In mid-April 1949, the "Rhodes" cease-fire agreement was signed, according to which Egyptian forces, accompanied by Sudanese, Libyan and Yemeni units, began evacuating their barracks and bases in preparation for leaving the South Jerusalem Front, including Beit Safafa, whose soil had been soaked by the blood of its sons.

In the memoirs of Hassan Ibrahim Othman, the son of the village, which he wrote under the title “Mountain and Snow… Memories of Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth in Historic Palestine 1940-1959,” he said that the mayors of Beit Safafa gathered in the center of the village to bid farewell to the protectors of the homes and the comrades in arms, and sadness hangs over everyone’s faces, especially after noticing movements Suspicion of the Israeli forces towards the village.

These forces fired heavy bullets from automatic weapons for 15 minutes during their incursion, reinforced by a few armored vehicles, after the mukhtars and the garrison command refused to sign a portion of Beit Safafa and annex it to the "newly Jewish" state.

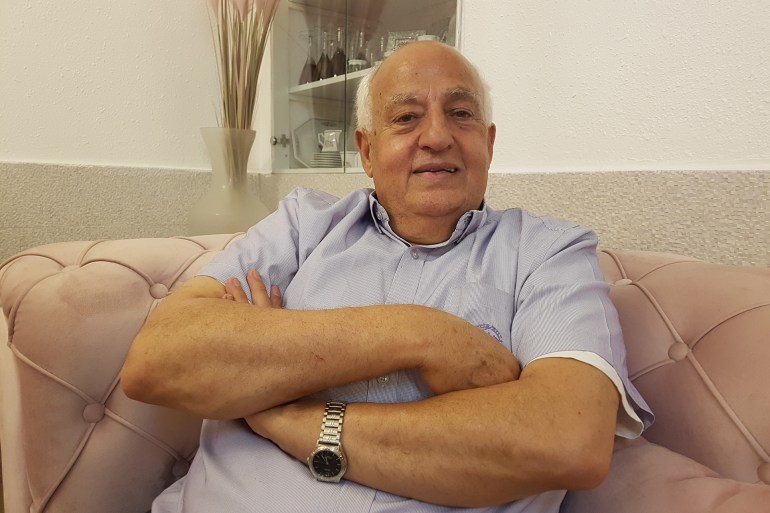

Issa Alyan is a witness to the period of dividing the village of Beit Safafa into Israeli and Jordanian parts (Al-Jazeera)

Dividing the village lands and the hearts of its children

One day after entering the village, the Israeli forces began erecting the barbed wire that penetrated and divided the main Beit Safafa Street and the village into two parts according to the "Rhodes Agreement".

The main motive for annexing part of Beit Safafa to the Israeli occupation was its greed for the railway that passes through the village and connects Jerusalem with the coastal plain cities. Thus, the section through which the railway passes came under Israeli rule and the other under Jordanian rule until 1967.

On the lips of those who lived through the partition period with what is popularly known as “the check” (barbed wire), the painful memories that accompanied them with joys, sorrows and feasts flow.

Al Jazeera Net walked towards the house of Issa Alyan, who was born 3 years after the division of the village and lived the dark details of daily life with the presence of the forced border wire.

When the new borders were drawn, his father's family was isolated in the Israeli section and his mother's family in Jordan, but his grandfather's fear of his father for his son pushed him to deport him and his family during the first hours of the occupation to the Jordanian side.

Alyan says, "I lived with my parents in my grandfather's house to my mother, and when I was 10 years old, I told my mother that I was determined to escape from a hole under the barbed wire to the occupied side to visit my grandfather's house to my father. to the city of Bethlehem and buy a large piece of meat as a gift for them.”

The home of the Alyan family, which the Jordanian army took as its headquarters during its rule, a part of the village (Al-Jazeera)

The separated family waited for the absence of the patrols on the border, and Issa's uncle, who is 4 years older than him, was waiting for him in front of the border strip on the occupied side.

"I lived the most beautiful days of my life in these days of smuggling. I sat on my grandmother's lap, visited the zoo, and ate delicious ice cream, before my father called me back with his intention to travel to Kuwait," he added.

The journey of exile did not last long, and the most difficult thing he experienced was the moments of his father saying goodbye to his family from behind the barbed wire at every departure from the village towards Kuwait.

In another house nearby, the ravages of the Nakba and the hardships of life were evident in the features of the elderly Badria Alyan, from Beit Safafa, who was born in 1942 and lived through the details of all the battles that took place around the village and on its lands.

"The day after the invasion of the village, I witnessed the demarcation of the border, and I remember that my uncle kicked the barbed wire and ordered them to remove it, but one of the soldiers responded immediately and said to him: Talk to the official, these are higher orders."

Over the course of an entire hour, Badria told Al Jazeera Net a stream of stories about the memories of the "check" that found herself and her family within hours on the occupied side after it was erected.

Elderly Badria Elyan (right) and Magda Sobhi recall the tales of forced borders in Beit Safafa (Al-Jazeera)

The harshest memories...death

"My six-year-old sister died in 1950 after she fell into a well, and when I divided the village, the cemetery became on the Jordanian side. After strenuous attempts, the Jordanian officer allowed my mother to cover her body with a blanket and drop it from the top of the check for my uncle to pick it up and bury it in the village cemetery."

In 1954, news came to her father that Israel intended to recruit all the girls living in the occupied part, so he immediately moved and threw a bundle of gold pieces inside to one of his relatives on the Jordanian side and begged him to get them out of the “Zone” (border) area.

The family actually moved to the Jordanian side through the "Mendelbom" gate, the only passage between the two parts of Jerusalem between 1949 and 1967.

Badria got married in 1962, and moved to live in her husband's family home, part of which was used by the Jordanian forces as a police station and prison. The memories she lived there until the removal of the barbed wire in 1967 were not nicer.

We were accompanied during our visit to the two homes by the daughter of Beit Safafa, Magda Sobhi, who documented in her book "Zaffa and Zaghrouda, O Girls" the songs and tales of weddings in the village of Beit Safafa.

"Zini silk is forbidden to me because our country has been divided into two.. Silk is forbidden to me. It is forbidden for me to jostle for the sake of your neighbor, O Beit Safafa.. As for our country, we protect it with gunpowder..

Sobhi also spoke about the ways and passwords that the villagers used in the illegal smuggling of goods and necessities from both sides of the enforced border.

Among the most important goods that were smuggled were coffee, rice, sugar, shoes, chicken, spices and cigarettes according to the needs of each side, and Sobhi stressed that the people on the occupied side lacked many basic needs in the light of an emerging occupied country.

Magda concluded her tour with Al Jazeera Net and spoke the most painful "check" story related to her grandmother's death in 1950 on the occupied side. She remembered that her grandfather then asked the occupation army to transfer her body to the Jordanian side, and he agreed, but the harshest stab he received from the Jordanian officer, who told him, "Take A little kerosene and matches, and cremation is better."

The grandfather was forced to bury his wife in the courtyard of the house, and Tammam lay there until 2008 when the family had to open the grave and move the remains to the Beit Safafa cemetery during a restoration of the historic house.