— Matthias, why did you decide to study Russian?

— I was 16-17 years old when the borders were opened.

It was interesting to look behind the Iron Curtain, I felt that the society there was changing dramatically.

Moreover, from Vienna to Bratislava - one day by bike.

And I, as a young student, traveled - practically without money, in search of adventure and new friends.

Traveled from Bratislava to Budapest, Prague, Poland.

In Vienna, I first studied at the Faculty of Economics, but I was not interested.

Then he served in the army, on the border with Hungary.

He stopped illegal immigrants so that they would not flee to Europe.

But I wanted to know what was happening in the east of Europe.

A new world opened up there.

And after the army I decided: I want to know this big white spot on the globe, which for me was Russia.

We knew practically nothing about it, only some more or less ancient notions and clichés.

And this is a huge part of the world, the largest country, the largest language.

From there, everything connected with the "Eastern bloc" began.

In the end, I chose history as the first subject at the university, and the Russian language as the second.

- Now you are helping Russian-speaking people who are in prison. How did you come to this?

- I ended up in prison quite by accident, if I'm joking, I was recruited.

In 2004, I finished my studies, and my teacher, for whom I wrote my thesis, a specialist in Russian history, said that a psychologist and a worker from prison came to him.

For the seminar, they were looking for a speaker who could tell something about Russian culture.

I came to the seminar, showed on the map where Chechnya, Georgia, Ukraine and so on.

But people were more important not so much what I say as I myself.

They said that they needed help - then a lot of Russians appeared in Austrian prisons with whom there were problems.

Several months passed, I had already forgotten about it, when they called me and said that I had received permission and could come to the prison.

At first I worked as a translator.

I had just started a family, I had not yet found a job, there was no fear or prejudice.

Decided: “Here, this is something new.

I'll work there for a while and see what happens."

I did not think that I would stay there for 15 years.

- Was it interesting?

— Yes, very much so.

Almost no one knows anything about the prison, except for those who were imprisoned and who work there.

There are different ideas, for example, someone believes that there is bread and water.

Personally, for the first time, the atmosphere reminded me of the army: the same beds, blankets.

I began to understand that a prison is just a part of any state.

And in it, as in a crooked, but still a mirror, all the problems of society are clearly visible.

For example, in the US, seven or eight times more people sit as a percentage of the population than we do.

In Russia, in my opinion, two or three times more than in Austria.

When many people are in prison, it starts to have a big impact on the population.

A certain culture becomes fashionable, for example, all sorts of tattoos.

- There is an opinion that in Russia a lot of people are in prison not because the society is so criminal, but because there are too many laws according to which terms are given. While for similar crimes in other countries - a fine, community service. Have you compared these things between Russia and Austria?

— Not that I scientifically analyzed it all, but I agree.

After the war, we had a big problem with crime.

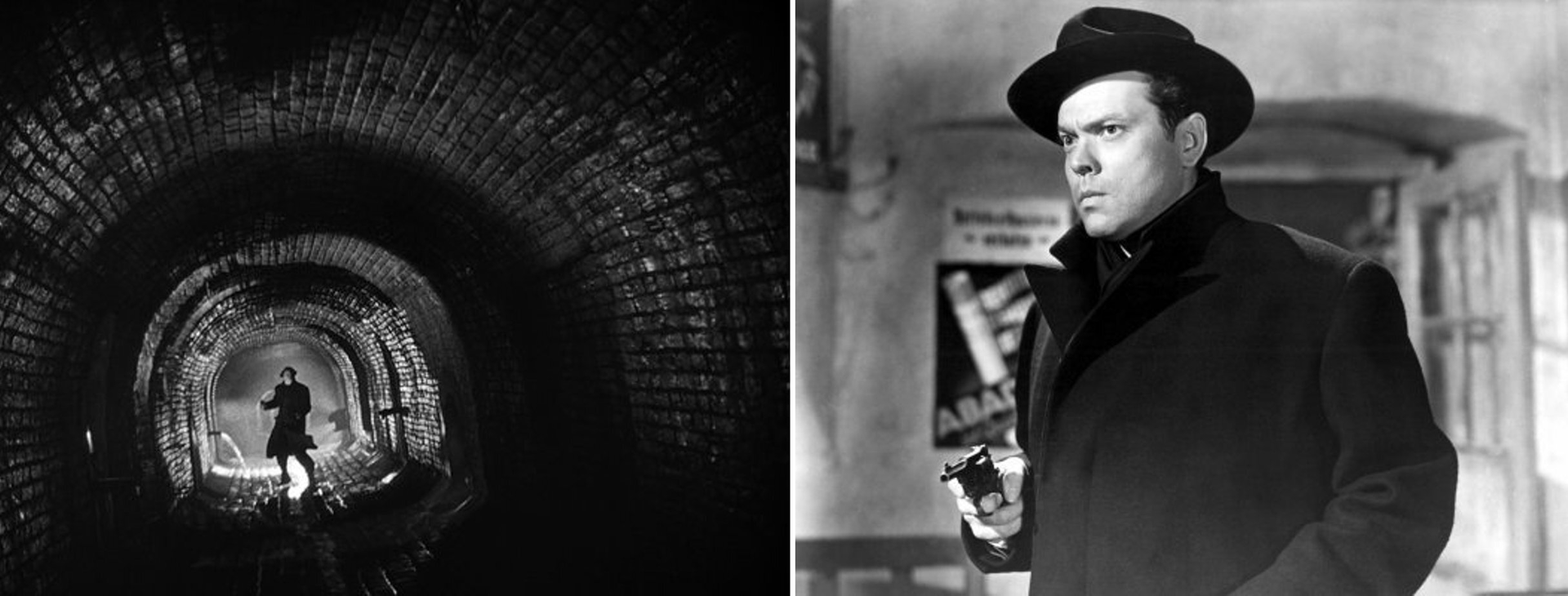

Stills from the movie The Third Man, 1949

- This is very well shown in the movie "The Third Man".

- Yes.

This is the only reminder.

But the policy in the 70s of the last century was aimed at trying to plant as few people as possible.

Prison became a last resort, and punishment could be in the form of social work.

Some articles were removed, for example, homosexuality - in the 60s we were also imprisoned for this, yes.

In the early 1990s, professional crime disappeared: burglars, pickpockets… They even thought of closing prisons.

But the communist system collapsed and new people came to us.

First, the Poles, neighbors from the countries of the collapsed Warsaw Pact.

And the next wave was from the countries of the collapsed Soviet Union, it came in the early 2000s.

Then we decided that we would not close the prisons, but we would send all foreigners to sit away from Vienna.

For example, there is a prison on the border with Germany, in a deep province.

It is very difficult to get there, only by bus, you have to go all day.

But since they do not have relatives here who would find it difficult to come on a date, they decided to send them there.

As the prison guards say: foreigners saved our jobs.

- Do you have the task of re-educating, directing in a different direction?

- Yes.

The purpose of prison is to correct people, to resocialize them.

I think almost everyone who works with me agrees to this.

But only the person who wants it will be corrected.

My task is not only to help people, but also the prison staff, in order to better understand why Russian speakers behave the way they do.

"Sanatorium with bars"

- What is the contingent now that uses your help in prison?

- The largest group of prisoners, if we talk about nationality, is from Serbia.

Their specialization is theft or drug trafficking.

— What about the Russian speakers you work with? Who are these people?

- At the beginning of my work, 15 years ago, almost none of the prisoners spoke German.

They just arrived, lived here in some refugee camps, or in hostels.

After the Chechen war, there were many refugees with problems that they brought with them, they were connected with the family, with drug use.

A certain proportion of people were criminals back in Chechnya, these are men who did not find themselves here and began, for example, robbing gas stations.

The younger generation of Chechens, of course, no longer understand Russian, they speak German, but they have their own problems, the issue of identity is acute for them, plus the problem of the post-war generation, it is always lost.

— Do you have wards from Ukraine with whom you speak Russian?

— Yes, of course, there are people from Ukraine.

Mostly from the west: Chernivtsi, Ivano-Frankivsk.

- Suddenly. Because it seems to me that they don’t speak Russian there in principle.

— If necessary, why not, they all own it.

I have not yet met a single Ukrainian who does not understand Russian at all.

We also have a Polish psychologist.

If they don't want to speak Russian, let them speak Polish.

They usually do car theft.

Mercedes Sprinter is the most favorite car of a Western Ukrainian.

A stolen car can be handed over to someone who will drive it to Ukraine.

The people who sit in this stolen car, hoping they can drive across the border without getting caught, are called "tankers".

They are simply put into this car, they say “drive”.

They travel for €200-€300, and then sit for six months in a pre-trial detention center.

- Who else among the Russian speakers uses your services in prison?

— Georgians.

With thieves' concepts, different tattoos, with thieves' romance.

But they did not know everything, because, firstly, this is a foreign country for them, and secondly, most of them were in prison for the first time.

They all knew how to behave ethically because they were told the right thing on the street, they grew up with this criminal culture.

But they did not know with whom they could cooperate, with whom they could not, they did not know at first how to contact me.

Many said: “I don’t understand Russian, that’s all.”

The inscriptions on the walls of the cells in the Vienna pre-trial detention center, made by Russian-speaking prisoners.

© From the personal archive of Matthias Morgner

And then, after a couple of days, they started talking.

They discussed whether it was possible to talk to me, one Georgian thief in law came and said: “So, everything is calm.”

And they all immediately began to stop using illegal medicines, drugs, stopped cutting themselves constantly, and so on.

And then I literally jumped into the cold water: then one cut himself, then the other, then there was some kind of fight, then some kind of lawlessness.

And I began to study this topic, I asked on the Internet who the “thief in law” was.

- Didn't this happen in the practice of the Austrian prison?

It wasn't developed that way.

In principle, the culture in prison is the same everywhere, but in the former Soviet Union it was the most developed.

I would even say in a positive way.

There is a very high standard of what is called honor, they call it concepts, prison laws.

There is an opinion that it was the influence of white officers who, during the Civil War, chose the path to the criminal world, ended up in prison, and created this order there.

Then there were many political prisoners.

Intelligentsia, priests even.

Therefore, the Soviet prison culture developed as an ideology in opposition to the culture of the regime.

- In the USSR there were also so-called "guilds". People who then wanted to do business. Highly intelligent, educated. They worked illegally, stole income from the authorities, bypassed taxes, but they didn’t kill anyone, they just wanted to live like the whole world lives. And many of them got out of prison in the 90s, when it became legal and, on the contrary, was encouraged. But very few people were able to find themselves in the new world.

Yes, I discuss these topics with the prisoners with great interest.

We have an old robber from Vyborg.

Let's call him Lyosha.

A common criminal, one of those who are engaged in robbery, a raider.

We have a sanatorium in the Vienna Woods, built back in the 19th century for girls from the bourgeoisie who fell ill with tuberculosis.

Today it is a prison for men who have also contracted tuberculosis, or for the old and sick who are in prison for a long time.

This is a sanatorium, but with bars.

Lyosha is 60 years old.

He sits there, in a sanatorium, with tattoos, all the bones are broken.

He began to talk about himself, it's like a show for YouTube: "How I started doing lawlessness in the Soviet Union."

Then he was 12 years old, he ran away from his parents for the first time.

And got on the train, he was caught.

He also remembers how much the fine had to be paid to his parents in order for him to go back to school.

And so he began to steal.

I got sick with everything, than you can get sick in prison.

The uprising was where he was sitting, in Murmansk.

Then there was the Vladimir Central.

He told how he was a thief.

This is a whole life.

And today how to fix this person?

Here, I suggest to him: it's time to retire, we must return to Russia.

"I like chanson"

- In Russia there is a whole culture of criminal, thieves' songs.

— Chanson.

- Do you listen to any songs? Like?

“Of course, I don’t understand everything.

To be honest, yes, I like music.

I like Russian chanson with its instruments - harmonica, guitar, and so on - much more than American gangsta rap.

But in reality it's the same.

— Artistic understanding of his criminal life.

- One Georgian thief who was sitting with us - chanson was also written about him.

All Georgians know his nickname.

They wrote a song about him and for him.

Icons of the Georgian thief in law in the cell of the Vienna pre-trial detention center.

The rosary of a Russian-speaking prisoner.

© From the personal archive of Matthias Morgner

Your experience and knowledge is simply invaluable. Do you share them?

— I teach at the school of security guards when they first start working.

My task is to prepare them on the topic of intercultural relations.

And this song is an example of the fact that we have people who even sing about.

- In fact, Russians also do not understand all the words that sound in Russian chanson. Because the so-called fenya is used there, a special language, many words of which come from Yiddish.

“Our Viennese dialect also has many such Yiddish slang words.

When many were in prison, between the wars, in the 20s, in the 30s, then these words spread into the common language.

Professor Mikhail Grachev has been studying Fenya as a phenomenon in Nizhny Novgorod for more than 25 years.

We met with him, and he explained to me what words from the German language are present in the hair dryer.

The word "ment", for example, from the German word "mantel".

Since in Western Ukraine the Austrian police wore such uniform coats, which they called "mantel", they began to be called "ment".

Then he explained to me why he chose this topic at all.

This is the science of prison culture in the Soviet Union.

Both the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the KGB, and not only in Russia, of course, are scientifically dealing with this topic.

Not only the language, but also tattoos.

There is even a Russian Tattoo Encyclopedia in English.

The professor explained to me how the system works.

They have five thieves in law in Nizhny Novgorod.

One, no matter who, must be in prison.

To watch.

And everyone else controls black markets or crime.

Nizhny Novgorod, he said, is traditionally a “red” city.

That is, there is no black crime here.

- Do your children show interest in the Russian language?

“They study at the only gymnasium in Vienna where Russian is the first foreign language.

English joins later, two years later, in the third grade.

— Do they like it? It is, first of all, your choice.

- Complex issue.

For them, this is just a fait accompli, although they understand that the choice is not ordinary.

But my motive is that it's like with musical instruments.

You force your son to play the piano, and when he is 15-16 years old, he says - I don’t want to.

OK.

At least some skills are left.

And, if necessary, they can be reactivated.

We do not know what they will do, but we have the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland nearby, and when they need to master any Slavic language, it will be much easier for them than if they know only English.