When physics laureate Syukuro Manabe made his first climate models in the 1960s, computers were so slow that he was forced to simplify.

Only the most important processes were included, such as solar radiation, water vapor, carbon dioxide and a reflective land surface.

The physics prize winner predicted today's warm-up

Still, he managed to predict that the temperature would rise 2-3 degrees when the carbon dioxide content doubles in the atmosphere of fossil emissions.

An appreciation that still stands well.

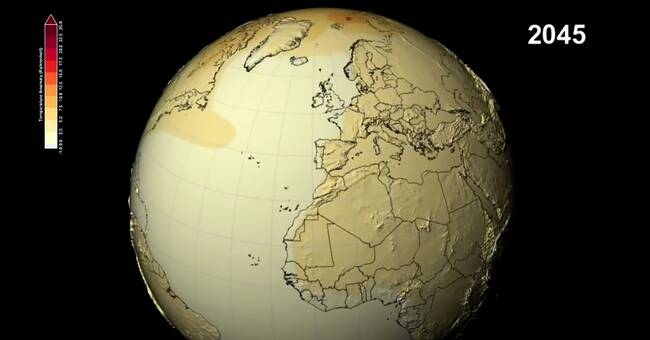

- It is fantastic, it looks just like a satellite film of the cloud cover, although it is created by a climate model, Syukuro Manabe exclaims when he looks at a climate simulation from the American research authority NOAA.

But according to Syokuro Manabe, there is also a problem with the new climate models becoming so advanced and incorporating formulas for many more climate gases, vegetation, ocean currents, geological processes, human activity and more.

The climate models become like a "black box"

- Our dilemma is that if you include everything that affects the climate in the computer models, they become so complicated.

The parts are hidden as in a "black box" and no one will dare to trust the climate models anymore, warns the 90-year-old Nobel laureate Syokuro Manabe.

But today active climate scientists do not fully agree with the criticism.

Today's complex climate models are always tested against real observations.

Regional climate models may start with historical weather data to see if they can recreate weather events.

Complex programs are required to predict the future

- They must include all processes that are relevant when talking about climate change in the long term, says Erik Kjellström who is a professor of climatology at SMHI.

- The carbon dioxide that we emit into the atmosphere does not stay there but much is taken up and disappears into the vegetation or in the oceans.

It must also be possible to count on these processes in the models so that they become increasingly complex in that way, Kjellström continues

One of the biggest challenges is that the supercomputers must have sufficient capacity to calculate the climate in the same detail as today's weather forecasts.

Only then can one emulate many extreme weather.

For Sweden, for example, it is still uncertain whether there will be more or less thunder in connection with future rainfall according to Erik Kjellström.

See more in The World of Science - climate crisis, feeling and chemical success 5/12 on SVTplay and 6/12 at

20.00 on SVT2.