At the height of the colonial era, specifically in the mid-19th century, universities were established in the colonies of the colonial powers by the elites of the European colonialists, who saw themselves as the "torchbearers of civilization and culture" in the countries of the primitive colonies.

More recently, within postcolonial studies, a critical understanding of this history and the role that universities played in the modern colonial context has formed.

Colonial Universities Alliance

On July 8, 1903, the first conference of the Allied League was held at the Cecil Hotel on the River Thames in London.

In his article for the Scottish newspaper, The National, Nicola Perugini, an academic and researcher in Italian and Middle Eastern studies at Brown University, wrote that the purpose of creating knowledge-producing institutions and university networks was to strengthen British colonial rule.

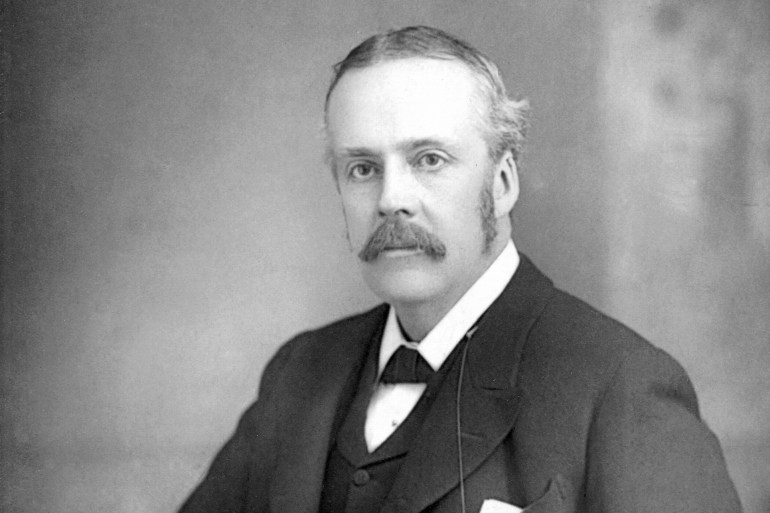

Arthur James Balfour, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and Chancellor of the University of Edinburgh, was one of the architects of this imperial shift towards academia.

At the Cecil Hotel, Balfour presided over a conference dinner which was attended by delegates from universities, college presidents, and "outstanding men in educational and scientific work".

After eating the usual toast, Balfour gave a speech celebrating the founding of the new British Colonial Academic Alliance, explaining why this was such a remarkable political achievement, and saying, "Here we represent what will become, I believe, a great alliance of the greatest educational instruments of the Empire; the alliance of all the universities that feel increasingly with its responsibilities, not only for the training of young people intended to carry on the traditions of the British Empire, but also (with its responsibility) to promote those great interests of knowledge, scientific research and culture, without which no empire, however materially admirable, can really say that it contributes its role in the advancement of the world.

Arthur James Balfour was Prime Minister in Britain from 1902 to 1905 and became Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1916 to 1919 (Getty Images)

colonial racism

In Balfour's mind, the new academic alliance was a crucial tool for the consolidation of Britain's global hegemony.

It was also a major tool to underscore a sense of Anglo-Saxon racial loneliness, as Balfour said in his speech at the dinner party, "We are proud of a society of blood, language, laws, and literature."

After ending his term as Prime Minister in 1905, Balfour withdrew for a decade from center stage in imperial foreign policy, before returning in 1916 as Foreign Minister, but during those ten years, Balfour - as Chancellor of the University of Edinburgh - continued to build a British academic space to be Imperial project.

Perhaps because of his growing interest in the "Orient", Balfour was asked in 1912 to preside over the session of the First Conference of the Universities of the Empire on "The Problem of the Universities in the East as to Their Effect on Character and Morals: The Ideal".

In his opening speech, he stressed that in Western universities, there was a "mutual adaptation" between scientific knowledge and social and cultural traditions, while in Eastern universities, science and social customs were on two collision paths.

The writer - who is the co-author of the book "Human Right to Dominate" - says that the idea of the inherent incompatibility between Eastern traditions and science is based on the concept of natural racial inequality that Balfour clearly explained several years before that in his book "Degeneration".

In that book, Balfour assumed that Eastern history was dominated by the monotony of tyranny and the inability of Orientals to govern themselves, and said that he could not believe that any attempt to provide a similar educational environment to different races would succeed in making them alike, because they are different and unequal since the beginning of history, and they will remain different and unequal.

Balfour Declaration

This kind of racist thinking shaped Balfour's making of the imperial world - as a statesman, a man of science, and an academic - and also formed the backbone of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which established a new imperial legal framework in the Middle East.

The declaration, which was issued on November 2, approved the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, while depriving the Palestinians of their national rights and granting them only their civil and religious rights;

In the end, in keeping with Balfour's writings, the Palestinians were treated as "Orientalists" incapable of governing themselves or achieving self-determination.

Balfour wrote and signed the declaration before visiting Palestine, and his first visit was in 1925, when he opened the Hebrew University in Jerusalem wearing the uniforms of the Universities of Edinburgh and Cambridge (where he also became an advisor in 1919), and as a guest of the Zionist movement, he toured the first Jewish settlements that were established In Palestine, including Balfoury, a settlement dedicated to his memory by the Zionist leadership.

In his inaugural address on Mount Scopus/Al Mashhad (northeast of Jerusalem), Balfour celebrated Hebrew University as an experiment in adapting “Western methods” (Jewish science and theories) to an Asian setting, and as an institution capable of reviving stagnant Palestine, as he put it.

The Israeli leader Chaim Weizmann (1874-1952), who played a crucial role in persuading Balfour to issue the 1917 Declaration, relayed in his autobiography, Trial and Error, that the Hebrew University was Weizmann's dream and was a crucial instrument of Zionist assertion in Palestine.

After the opening, the Hebrew University was included in the network of Imperial Allied universities that Balfour had helped form at the turn of the century.

Decolonization in universities

The link between Balfour's contribution to imperial rule and his contribution to the development of the British Imperial Academies has for some reason been erased from collective memory, and does not appear in the vast amount of contemporary literature and debates about his involvement in global imperial affairs and his notorious sin, in the words of the writer who serves as a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Science. Social and Political at the University of Edinburgh.

For this reason, continues Nicola Perugini, "we may use this year the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, to rediscover this connection and to raise some fundamental questions."

He continues, "As British universities that officially and publicly adopt a decolonization agenda, and try to decolonize curricula and academic spaces, how can we decolonize our historical narrative when it comes to the injustice suffered by the Palestinians as a result of the imperial declaration issued by one of our advisors?"

"Why do we not publicly acknowledge that the man who was appointed to enhance Britain's global academic reputation for 4 decades was also a major political and intellectual actor in the production of a racist imperial system that expelled many peoples? What would the implications of such recognition be?"

He added, "Since the question of Palestine is still alive as a colonial issue, which continues to generate violence and dispossession, how can we contribute - with concrete and tangible institutional measures - to the decolonization of Palestine and reform the University of Edinburgh's involvement in an ongoing colonial settlement project to deprive Palestinians of the right to self-determination and uproot them? of their land?"

"In the end, after all, the Balfour Declaration was also the announcement of our university president," concludes the academic at the University of Edinburgh.