The recent official Egyptian positions in the Renaissance Dam crisis mark a remarkable transformation, as the sharp tone adopted by Cairo towards Ethiopia has escalated, after Cairo has long bet on a political solution as the only alternative to deal with the crisis. The most prominent evidence of that transformation is the recent Egyptian movements in the Nile Basin led by Lieutenant-General Mohamed Farid Hegazy, Chief of Staff of the Egyptian Army, in the past three months, which culminated in the signing of four military and intelligence agreements with Sudan, Uganda, Burundi and Kenya, amid Ethiopian silence. On the background of these visits and their outcomes, which may be seen in Addis Ababa as a prelude to hostile action, especially as it restores a stifling geographical situation similar to the Egyptian presence in the Nile Basin region a century and a half ago; Ethiopia was surrounded on all sides by lands belonging to the Egyptian Empire.

In the current conflict, Egypt fears that its share of the Nile water will be affected by the Renaissance Dam, and is also seeking to guarantee its annual share of water - 55 billion cubic meters - in addition to signing a comprehensive agreement on the management of the dam. Ethiopia says any binding framework regarding the management of the dam is a derogation of Ethiopian sovereignty that it will not allow. While the signs of war seem likely due to the failure to reach an agreement, in the end each conflict remains dependent on its facts. The balance of political power has changed over the past fifty years, and Egypt no longer enjoys the same weight it enjoyed in Africa during the 1960s and earlier. The issue of the Nile waters and the Renaissance Dam, which did not go in Cairo’s favor over the past decade, is evidenced by the fact that Cairo fears that it will devolve into a fait accompli that does not meet its interests.How did Egypt lose its power cards in the Nile Valley? What efforts are being made to restore it this year? And what is the step that can make the war card present on the ground, and not only as a diplomatic pressure tool?

There are several historical and political complications associated with controlling the sources of the Nile, whose modern precursors began with Muhammad Ali’s assumption of the rule of Egypt and his achievement of political independence from the Ottoman Empire, in addition to the establishment of an Egyptian regular army, events that later established a new rule equation by establishing an Egyptian empire that derives its strength from Expansion throughout its surroundings. But the south, in particular, was of great importance to the ruler of Egypt at the time; In addition to the gold and soldiers that Sudan could offer, the control of Abyssinia, including the sources of the Nile, and the Horn of Africa region, constituted a permanent guarantee for the complete security of the Egyptian Empire. (1)

The Egyptian expansion in the continent to the south began in 1820, but it stopped at Sudan. With the arrival of Khedive Ismail to power in 1863, the ambitions of expansion were renewed, supported by the lessons of the past. The Khedive moved away from the Levant and focused his attention on the Nile Valley;

Seeking to establish an Egyptian empire in Africa, an expansion that embodied the empire of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) its main obstacle as a geographical fortress impenetrable, even before the major colonial powers.

The Emperor of Abyssinia requested military aid from Britain to establish a Christian kingdom at that time and stand up to Egypt.

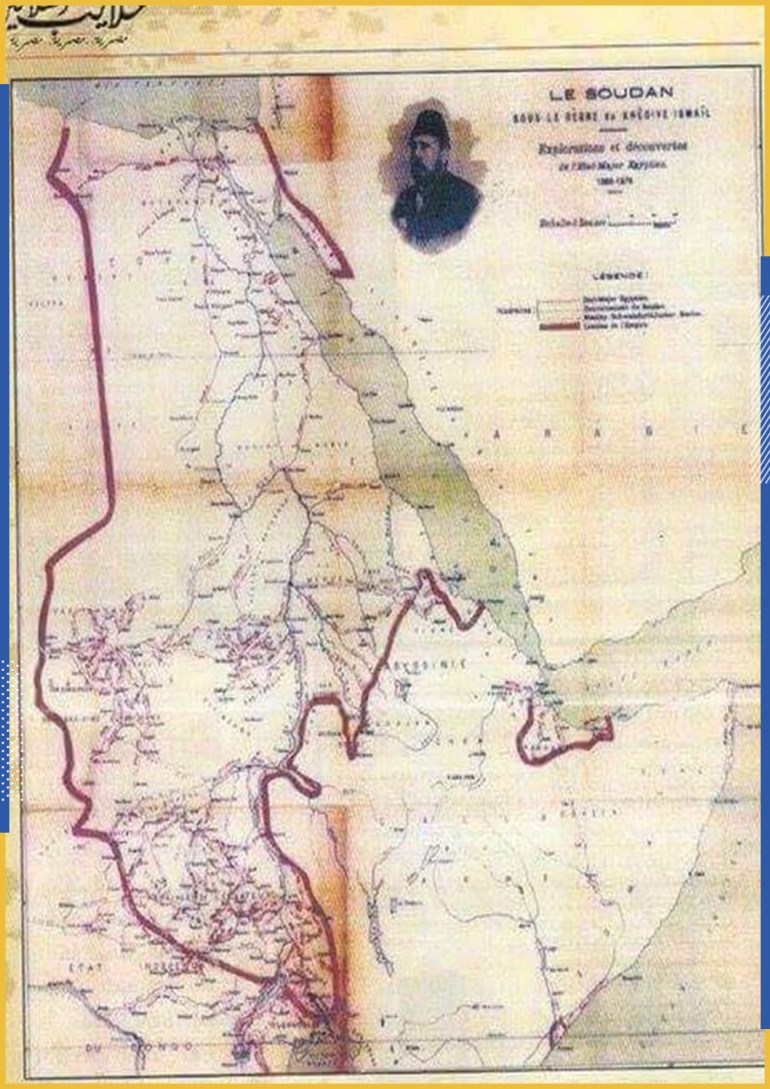

Map of the Egyptian Empire during the reign of Khedive Ismail

Within a few years, Khedive Ismail succeeded in annexing Darfur in western Sudan, imposing his influence on the coasts of the Horn of Africa, and all the ports overlooking the Red Sea, including Suakin on the Sudanese coast, Massawa in Eritrea, and Zeila port on the Somali coast, and then controlled the Bab al-Mandab Strait. , placing the entire western coast of the Red Sea under Egyptian sovereignty. The Khedive continued his military campaign in the south, reaching southern Sudan, then Uganda, Tanzania, and Lake Victoria. His control of the Nile from the source to the estuary was completed, and the Egyptian flag flew over those vast lands, all the way to the Equator Directorate. (2)

In the end, Khedive Ismail succeeded in establishing a political unity for the countries of the Nile Basin, but the Egyptian expansions stifled Abyssinia geographically from the north and west, and with the Egyptian control of the Red Sea coasts from the east and south, Cairo effectively encircled Ethiopia by land and sea. Although Britain obtained a pledge from the Khedive not to invade Ethiopia, as it is the source of the Blue Nile, this did not end the fears of "Theodore II", King of Abyssinia, who had previously demanded that Britain provide him with weapons and ammunition to counter the Egyptian advance. Tudor's request did not meet Britain's response, and then the escalation began, and the English ambassador and a number of British nationals were kidnapped inside his country, and when he did not respond to British threats, Britain in 1868 moved an army of 13,000 soldiers, and Egypt officially asked permission for the forces to pass through its territory.The battle ended with the king’s suicide, and the kidnapping of his young son from Abyssinia to Cairo, before he was led captive to Britain, where he died and was buried there, and his remains have not been returned to this day.

The defeat deepened the hatred between the Egyptian and Ethiopian empires, especially since the war came after the failure of talks regarding Egyptian expansion, which caused Ethiopia to turn into a landlocked state.

After Egypt annexed the Bogos region of southern Sudan, Ethiopia protested and considered it as its lands. It launched attacks on the adjacent Egyptian border, and then Egypt sent two military campaigns in 1875 and 1876 to invade Abyssinia, but they were unsuccessful. At that time, there is also in Ethiopia until this moment a high military medal in the name of "Gundt", which is the name of the same battle in which they defeated Egypt.

The complexities of history still govern each side's perceptions of their rights to the river.

For its part, Egypt sees that undermining its role in the continent comes first by cutting off the Nile waters, at a time when Ethiopia is promoting its project as a leap in its quest to advance the country economically and occupy a more prominent position on the African arena.

In the same year in which Egypt lost its war with Ethiopia, Cairo declared bankruptcy due to the debts and money that Khedive Ismail was extravagant in borrowing and spending, so that the star of the empire began to decline later as a result of the British occupation. Although the Egyptian borders have receded to include Egypt and Sudan only, away from the Horn of Africa and the sources of the Nile, Cairo's influence in the Nile Valley and Africa has not diminished despite the impact of the occupation. Britain maintained Egyptian influence in the upstream countries through the 1902 agreement, signed with the then King of Abyssinia, in which he pledged not to build any dams on the Blue Nile, Lake Tana, or the Sobat River, that would prevent the flow of the Nile waters, except with a previous Egyptian approval. The Emperor of Abyssinia had no choice but to acquiesce in Britain's demands.

Egypt crowned its control of the Nile in 1929, when it signed an agreement with Britain that gave it the right to veto any projects in the Upper Nile that might affect its share of the water, and "Britain" at this time represented countries under its direct political sovereignty, such as Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Sudan. In 1959, Egypt and Sudan signed the agreement to share the Nile waters, so that Egypt gets 55.5 billion cubic meters annually, while Sudan gets 18.5 billion cubic meters, treaties that Ethiopia is currently rejecting, as it considers them to be legal because it did not participate in them, as it describes them as agreements Colonialism because it was actually signed with the British officials who occupied the region and not with the countries themselves after their independence.

Even after the departure of the British occupation, Egypt maintained its African influence, through the national project led by President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who maintained Egypt's influence in the Arab world and Africa. At that time, Egypt inaugurated the High Dam project despite the objection of the weak Nile Basin countries, and the project passed peacefully as a result of the friendship that brought together Nasser and the Emperor of Ethiopia, "Haile Selassie". However, Nasser's departure put Egypt on a different path under the presidency of Anwar Sadat and his close alliance with the United States. Egypt adopted policies that support right-wing dictatorships and stay away from liberation movements. Hence, many African countries stood against Egypt’s policies, a shift that included the “history” complex into the “geography” complex.

In 1977, in front of a crowd of half a million Ethiopians chanting against “Cairo” in Al-Thawra Square in Addis Ababa, Ethiopian President Mengistu Heila smashed six bottles of blood in the name of Egypt, which he accused of supporting chaos within his country in favor of Western imperialism. Although Mengistu was an authoritarian ruler and not a freedom fighter, the role that Egypt played in Africa during that period and its bias against the anti-US regimes, especially the socialist “Mengestu” regime, was one of its major sins that paved the way for political impasses that will not end in the Nile Basin. . Almost half a century has passed since Egypt joined the "Safari" club.Under the leadership of the United States, which aimed to carry out intelligence operations against the socialist countries in Africa in alliance with France, Israel, the apartheid state in South Africa, Saudi Arabia and Pahlavi Iran, and is attributed to him the military intervention in the countries allied with the Soviet Union, where he intervened militarily in Zaire, and also supported Somalia in its war with Ethiopia.

Therefore, Egypt abandoned its role as the Kaaba of revolutions and liberation, and turned into the policeman of the Western brown continent, and many African regimes did not forget that coup in the corridors of Egyptian diplomacy in favor of the West at their expense. It is a revolution that still echoes today. The debate continues between liberation and revolutions on the one hand, and dictatorships supported from outside the continent on the other, and it may have caused the extreme sensitivity with which African countries received the news of the military coup in Cairo in 2013, after which the African Union decided to freeze Egypt’s membership for six years, before it returned The water flows into its courses, and President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi himself will become the president of the African Union in 2019.

That year witnessed an attempt to adapt the union to serve Cairo's regional interests and the agenda of its political system at the same time. The Egyptian role in Sudan disappeared during the weeks of the Sudanese uprising that confused the military regime in Egypt, and even Cairo tried to obstruct the transfer of power to civilians in Sudan after the overthrow of Al-Bashir’s rule. At a time when the African Peace and Security Council asked the Sudanese Military Council to hand over power to a civilian transitional government within 15 days, Sisi held a mini-African summit, in which he announced his coup against the Peace and Security Council’s decision, and gave Sudan’s military three months to hand over power to civilians. Once again, Cairo stood on one side, and liberation and revolutions were on the other. The revolutionaries, the sit-in in front of the General Command of the Sudanese army in Khartoum, rose up in demonstrations in front of the Egyptian embassy.

Khartoum only emerged from the dark tunnel at the time with the help of the Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who had just arrived to rule Ethiopia on reformist grounds (before that reformist tone quickly faded and revealed his ugly, authoritarian face in just two years). At that time, Abiy succeeded in mediating between civilians and the military in Sudan at a moment when everyone felt Egypt's absence from its natural role as a result of the burden of the political agenda of the ruling military regime. Before the outbreak of the Tigray region crisis and Ethiopia's slide into civil conflict again, Abiy Ahmed assumed the presidency of the "IGAD" organization, which brings together East African countries, and he has worked to zero in on the problems of his neighbors and mediate between them to resolve political differences through diplomatic means in order to enhance the Ethiopian presence. His efforts soon reflected on the support of some of his neighbors during his war against the Tigray region, as well as in the crisis of the Renaissance Dam.Abiy promises his neighbors economic prosperity after the start of operation of the dam, as Ethiopia plans to fill the electricity deficit in its neighboring countries, which has already rushed to sign several agreements to import electricity from Addis Ababa.

Egyptian sins accumulated for many years until Egypt began dusting off its important African files when the Renaissance Dam negotiations reached a dead end recently, and then the Egyptian movement finally began in the Nile Basin countries under the auspices of the major leaders of the Egyptian army during the past months, especially with the decline in Ethiopia’s international reputation and its occurrence Once again, in the quagmire of a civil conflict that formed an outlet for Egyptian politics. With many positive shifts in foreign policy, Cairo embarked on inaugurating successive economic and military agreements with East African countries, and for the first time waved the military action paper as an indirect wave on the tongue of President Sisi, even if his foreign minister blundered between reassuring the Egyptians at times that filling the dam would not affect them. And hinting at another time that Egypt will not allow it to happen without an agreement.

Egypt does not have geographical borders adjacent to Ethiopia, nor does it have a hand to reach the source of the threat posed by the Renaissance Dam, which deepens questions about the cost of the military option, and raises concerns about its feasibility and effectiveness. Although the desire to fight may already be present in the Egyptian army, which has long been on the list of the best Arab and African army, the vocabulary of war this time is variable, and does not depend only on what the weapon may make. It is certain that an act of this magnitude will set off a volcano of anti-Egyptian sentiment in Ethiopia and a torrent of international and legal troubles. In addition, there is no evidence to confirm that targeting the Renaissance Dam will make Ethiopia reluctance to build another dam or seek to reduce Egypt’s share of the Nile water again in the future, not to mention that Egypt does not yet have an idea about the countries that may support it in the Nile Basin after decades of its absence from the region.

The crisis is rooted in geography from the outset; In addition to the fact that Egypt and Sudan are located at the bottom of the Nile, about 80% of its water originates mainly from the Ethiopian highlands, which gives Addis Ababa a natural possibility to put pressure on Cairo. Despite Egypt’s shrinkage in Africa, with the exception of late moves, and the growth in the influence of some Nile Basin countries, led by Ethiopia, there is a huge gap that still separates the Egyptian army and the state and their counterparts in the Nile Basin, a gap that means that the theoretical possibility of war and an Egyptian victory in it is not a difficult matter. Numerous complications prevent the Egyptian regime today from actually playing the war card.

The complexities of the first war start from politics, not the battlefield. Targeting the dam in the presence of the Agreement of Principles, signed in March 2015, is a hostile act in the eyes of international law. The agreement provides for allowing the three countries (Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia) to build dams on the Nile River to generate electricity, which means Egyptian-Sudanese recognition of the legitimacy of building the Renaissance Dam. In addition, the agreement itself granted Ethiopia full authority to build dams without guarantees or oversight, and implicitly granted the African Union the right to freeze Egypt’s membership if the latter targeted the dam militarily, and Ethiopia has the right to file a complaint with the Security Council. While the agreement includes a clause on settling disputes and how to arrange issues related to the negotiations, Ethiopia has interpretations of the agreement of principles that it finds sufficient to win any case before the International Court of Justice, a proposition that Washington later confirmed by noting that the tripartite agreement does not include binding clauses to preserve Egypt’s share of water.

The geographical dimension between Egypt and Ethiopia imposes a costly economic dimension to the war, as it imposes a political dimension on the necessity of involving an external party surrounding Ethiopia geographically: Who would agree to strike the dam then? Egypt is not expected to receive African support at a time when the Ethiopian prime minister has made an umbrella of regional allies. Because Egypt does not have any military bases in Africa, it will have to cross Sudan first or pass through any country surrounding Ethiopia to reach the dam, and it is not expected that any of those countries will agree to enter into a conflict of this kind. Addis Ababa had previously signed a joint cooperation agreement with Sudan and South Sudan, and sent an official warning to the region of "Somaliland", which is not recognized internationally, against the background of African press leaks that revealed that an Egyptian delegation discussed plans to establish a military base there.

Although Juba is publicly neutral towards the Renaissance Dam crisis, and recently signed a military agreement with Addis Ababa, it actually moved previously to obstruct the Ethiopian move in the water conflict, and formed an anti-Ethiopia alliance by trying to persuade countries not to agree to the "Entebbe" agreement to divide the Nile waters. For years, South Sudan, through its president, "Salva Kiir", declared that his country would not move against Egyptian interests regarding water issues. However, a dividing line remains between siding with an ally's position in a conflict and being drawn into a war on its behalf, which could expose South Sudan to emphatic sanctions from the African Union.

Obstacles to the military option to deal with the Renaissance Dam crisis are revealed by secret documents of the Egyptian intelligence during the era of ousted President Hosni Mubarak. According to internal emails issued by the US intelligence company “Stratfor” for the year 2010, quoting the Egyptian ambassador to Lebanon, then Director of Intelligence Omar Suleiman developed three possible scenarios for targeting the Ethiopian dam, all of which require cooperation from other parties with Egypt: The first is through aviation with the help of a state The second scenario is the use of the Thunderbolt forces to carry out an act of sabotage, which requires access to one of the countries that have a direct border with Ethiopia, and the last scenario includes making friends with the enemies of Addis Ababa by supporting Uganda, South Sudan and Eritrea, and providing support to the Ethiopian armed opposition to carry out operations against the dam.

In addition to this, the accounts related to Sudan, which is the country closest to Egypt at present, besides the complexities of politics and history, there are also economic considerations that complicate Khartoum’s calculations. After the first filling, the dam reserved about 4.9 billion cubic meters of water, in addition to its current plans to store about 13.5 billion when the second filling is implemented, which means that the result of targeting the dam will be catastrophic for Sudan, which will witness a devastating wave of torrential rains whose humanitarian and economic consequences will be many times greater than It happened late last year, when the level of the Nile reached its highest level in a century, and caused the collapse of 100,000 homes and affected about half a million people; Hence, Sudan has strong reasons for not agreeing to the military option given the "complexities of the economy" in the first place.

It is certain that Egypt’s loss of the diplomatic battle of the Renaissance Dam, without alternative solutions, will have political and economic consequences, perhaps the worst of which is the threat to Egypt’s share of the Nile water, and Ethiopia’s mobilization of the Nile Basin countries to complete the signatures of the “Entebbe” agreement, which is an official coup against the historical water shares of Sudan and Egypt. The roots of this thorny agreement go back to 2010, after five countries ratified the agreement: Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda and Burundi. Under international law, the agreement can enter into force if two thirds of the Nile Basin countries have ratified, that is, seven countries, which means that the legal quorum will not be completed without the signature of one other country.

According to a remarkable statement by the Egyptian president, between 2014-2019, Cairo incurred about 200 billion Egyptian pounds ($12.7 billion) to provide 1.5 million cubic meters of water per day. If the crisis continues until 2037, Egypt will have spent 900 billion Egyptian pounds ($57.2 billion) on water, a figure equivalent to about 40% of the budget currently. If Egypt cuts off its share of water, it cannot desalinate about 55 billion cubic meters of water, because the quantity will require a huge budget, and these are long-term economic complications that will not be resolved by urgent decisions previously taken by the government to avoid the effects of filling the Renaissance Dam by lining canals and preventing the cultivation of water-hungry crops And the establishment of desalination plants for sea water.

Egypt will also not be able to resort to international arbitration for the most part. According to Article 36 of the Charter of the United Nations, no country may resort to the International Court to present any dispute that may arise between it and another country without the consent of the opposing country. Ethiopia has previously publicly refused to resort to international arbitration, which is a narrow path that pushes Egypt to negotiate to the end, or to resort to a military solution in the end. According to an Egyptian intelligence document published by WikiLeaks, dating back to the rule of ousted President Mubarak, Egypt believes that the Ethiopians are mainly aiming to push Cairo to respond in the wrong way, and therefore Egypt remains committed to a high degree of restraint and to resort to diplomacy and the negotiating table. (3)

Cairo insists so far on a political solution as the only alternative to address the crisis, so in November 2020, its president visited South Sudan, on a first-of-its-kind visit focused on reviving the stalled Jonglei Canal project, the same goal that necessitated another previous visit. To the Director of Egyptian Intelligence, Major General Abbas Kamel. The canal is an ancient Egyptian ambitious project that began to be implemented in the seventies, and it includes the construction of a 360-kilometre canal between the White Nile and the swamps of southern Sudan, from which Egypt and Sudan benefit by adding about 5 billion cubic meters of water to the Nile River, although the project remains of about 100 km , it is facing a funding crisis, and outstanding financial issues between the two downstream countries.

In the event that Egypt decides to resort to a military solution, it may refer to the old intelligence papers that are based on carrying out sabotage work in the body of the dam through forces loyal to Egypt, in addition to a limited military attack so as not to lead to deadly floods in Sudan. But at the moment, Egypt is taking the diplomatic path until the last breath, waving the military action paper in order to diplomatic pressure, and hovering around Ethiopia with a series of politically pressing military and intelligence agreements, but without real military action on the horizon.

The Egyptian desire and capacity for war, then, is still lacking. The ability needs to redress the legacy of half a century of wrong policies in Africa, and the desire is limited by what burdens the military institution in managing all internal and external files in the country after 2013. As for the road, it has become partially paved with good relations with South Sudan and the new Sudanese administration, and the significant decline in stability and security in Ethiopia, and the first step is the withdrawal from the Agreement of Principles signed in 2015, which makes all the works of the Renaissance Dam so far illegal, and thus paves the way for a completely different scene to that narrow tunnel in which the crisis has been going since Almost a decade.

___________________________________________________

Sources:

Sudan from Ancient History to the Journey of the Egyptian Mission (Part One) pp. 17, 117, 135.

The Egyptian Empire during the reign of Ismail and the Anglo-French intervention (1863–1879).

Egypt source

Agreement for the Declaration of Principles of the Renaissance Dam signed in March 2015.

Memory of Contemporary Egypt