An international research team led by the University of Goettingen and Madrid described the internal tree-like anatomy of symbiotic worms, for the first time, and researchers discovered that the intricate body of this interesting animal is widespread in the ducts of the host sponge.

The team described the animal's anatomical details and the nervous system of its unusual reproductive units in a recent paper published in the Journal of Morphology on April 4.

The posterior ends of several single worms can be seen as white lines creeping across the surface of the sponge (Glaspie - University of Göttingen)

The strangest worm on the planet

The marine worm known scientifically as (Ramisyllis multicaudata) that lives inside the inner channels of the sponge is one of only two species that have a branched body, with one head and multiple back ends, and may be the strangest worm on this planet.

It was first discovered in 2006, officially described in 2012, and found in Darwin Port, Australia.

And it lives symbiotically inside both the white and purple sponges, and this worm inhabits the inner part of the sponge except for the tips of its branches, and it is difficult to locate it when dissecting the sponge because it is not visible to the naked eye.

This family of polychaete worms is found in a range of habitats, actively moving on rocks and sandy substrates, burrowing in crevices and between seaweeds, and climbing sponges, coral reefs, seaweeds and mangroves.

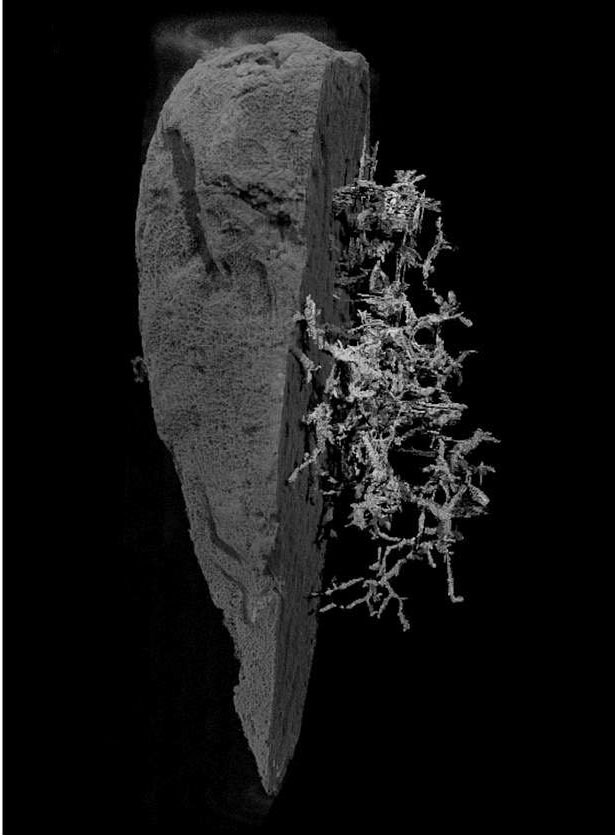

Image showing the complexity of the branches of this strange marine worm (Hamel - University of Göttingen)

Lateral branches occupy the channels in the sponge, and their ends sometimes appear in open water, making that sponge appear to have white hairy claws.

It is a branched worm whose head is hidden deep inside a sponge, branching again and again, forming a tree-like structure.

Some branches of the worm develop into stomata, which are reproductive elements that contain the eggs or sperms that are subsequently separated from the mother worm.

Detailed study .. the first time

Now, for the first time, scientists have studied its anatomy in detail, finally discovering more about this mysterious creature and asking more questions about how it lived and its strange life.

The research team collected samples of worms and host sponges, some of which are now in the collections of the Museum of Biodiversity at the University of Göttingen, and have integrated techniques such as optical electron microscopy, immunochemistry, confocal laser microscopy, and computed X-ray microscopy to analyze the samples.

They were able to obtain three-dimensional images of each of the various internal worms' organs inside their sponge.

And the scientists showed that when the body of these animals divides, all of their internal organs also divide, which was not known before.

Small fraction of a single living sample of the host sponge shown by a stereomicroscope (Bones Sigril, Aguadu and Glaspie - University of Göttingen)

Three-dimensional models developed during this research provided a new anatomical structure for these animals, consisting of muscle bridges that intersect between the different organs whenever their bodies had to form a new branch.

These muscle bridges are necessary because they ensure that the bifurcation process does not occur in the early stages of life, but rather as the worms become adults.

Moreover, the researchers suggest that this unique "fingerprint" of muscle bridges makes it theoretically possible to distinguish between the original branch and the new branch in each bifurcation of the complex body network.

This new study investigated the anatomy of the reproductive units known as "stolons" that develop in the hind limbs of the body when these animals are about to reproduce, a feature of the Syllidae family to which they belong.

The results show that these substrates form a new brain and have eyes of their own, and this allows them to move in their environment when they are separated from the body for fertilization.

This brain is connected to the rest of the nervous system by a ring of nerves that surround the intestine.

Solve some puzzles

Senior author Dr Maiti Aguado, from the University of Göttingen in Germany, explains in a university press release, “Our research solves some of the mysteries that these strange animals have raised since the discovery of their first branching rings at the end of the 19th century ″. A long way to go to fully understand how these wonderful animals live in the wild. "

For example, the study concluded that the intestines of these animals can be functional, yet no trace of food was seen inside them, so their ability to feed their large, branching bodies remains a mystery. Other questions raised in this study include: How are blood circulation and nerve impulses affected by the branches of the body?