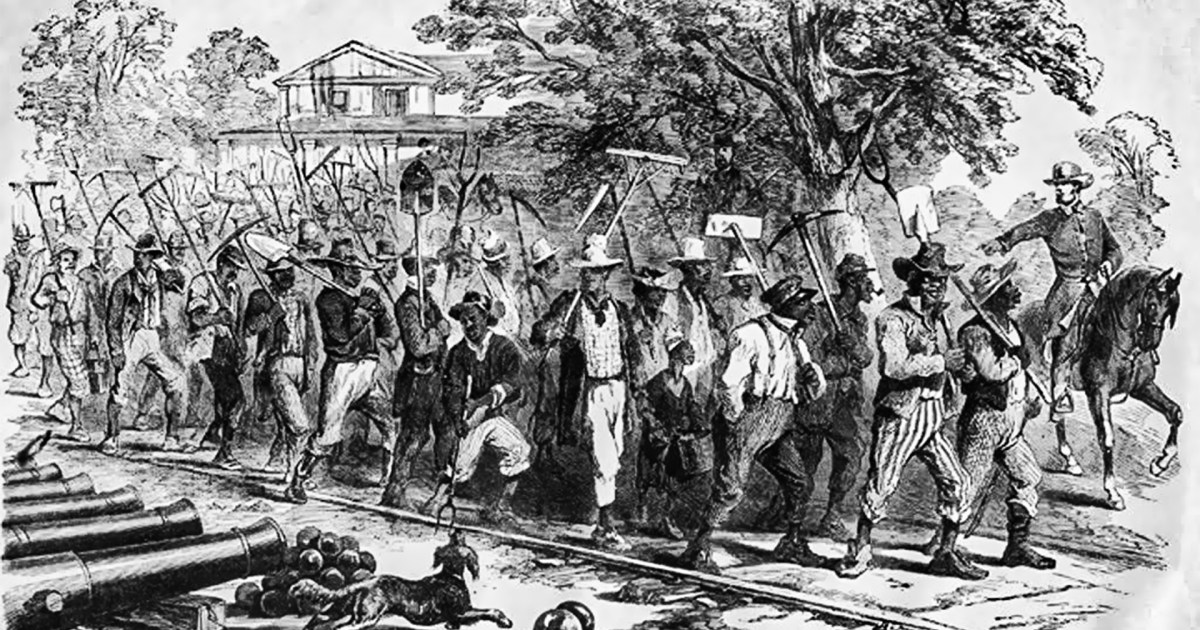

The transatlantic slave trade was not supposed to continue in the United States until the Civil War, and it was not supposed to be a substantial source of profit for the northern states in favor of abolitionist slavery.

In his report published by the American site "History", writer John Harris said that even after Congress banned the participation of the United States in the transatlantic slave trade in 1807 and classified it as a piracy activity in 1820, this illegal trade continued.

At that time, American "corrupt" shipowners, merchants, seafarers, and officials stationed largely in New York City cooperated with foreign allies, to continue shipping captured Africans through the Middle Pass until the 1860s.

Not only did this practice cause terrible suffering to enslaved Africans;

It also deepened the national divide over slavery, a rift that helped pave the way to the bloodiest conflict in US history (the Civil War).

The slave trade continues

The writer mentioned that the United States was not the only country to ban the slave trade at that time, as many countries known as the slave trade had abolished it by 1836;

But that did not end anti-black racism or eliminate the profit motive.

Global demand for sugar, coffee, and cotton grew dramatically in the 19th century, and farmers in the Americas relied on slaves.

Traffickers themselves had significant incentives to challenge the international abolition of the slave trade;

Their profits increased by 90%, a 10-fold increase over the previous century.

From the start the United States played a major role in this illegal trade, as slave traders brought about 8,000 prisoners (slaves) into the American South in the decades after the 1807 embargo, including hundreds just before the Civil War, and among the last were those brought. To American soil we mention Oluwali Kosula, whose name changed to Kodjo Lewis, a young Yoruba (the largest ethnic group in Nigeria) who sailed on board the Clotilda, the last slave ship that reached the United States in 1860. Before his death in 1935, Cossula conducted a series of Interviews with anthropologist Zora Neil Hurston, in which he recounted the shock of being arrested, sold, and shipped to a foreign place to live and work as a slave.

The largest contribution was the use of American ships to bring in slaves.

Slave traders liked fast ships like the Baltimore Clipper, which could outrun anti-slavery patrols, and the US government also refused to allow other countries to intercept ships owned by US citizens.

As a result, slave traders poured in across the Atlantic to acquire the United States flag.

In the end, half a million captive Africans arrived in Brazil and Cuba in American slave ships in the years after the transatlantic slave trade was banned.

In the 1850s, a daring group of slave traders known as the "Portuguese Company" set up their headquarters in New York City, and led by Manuel Kona Reyes, a Portuguese trader who traded in enslaved Africans in Brazil and Angola, this group bought second-hand ships in the vast freight market in Manhattan.

Then she worked with American sailors, ship merchants, and corrupt officials, such as Marshal Isaiah Reynders, to sail ships to Africa on voyages they claim were legal.

New York became notorious internationally in these years, especially with the booming of the slave trade to Cuba, as the main destination.

After 1850, nearly all slave traders were Americans, and most had ties to New York.

Unrecognized supporter of the abolition of slavery

The writer noted that the British authorities were among the most vocal opponents of the slave trade.

Since the US government largely turned a blind eye to this illicit trade and remained unwilling to allow the Royal (English) Navy to block the path of American slave traders, British Consul in New York Sir Edward Archibald took matters into his own hands by appointing a spy named Emilio Sanchez. He is one of the most unknown abolitionists in American history.

Sanchez was born in Cuba, immigrated to the United States, and became a ship owner and merchant in New York.

After his clash with members of the Portuguese company, he was eager for revenge;

So he interviewed Archibald and agreed with him for 400 pounds a month in addition to bonuses for every flight canceled thanks to his information.

Sanchez used his knowledge of docks, and for three and a half years, he was spying on slave traders, watching their movements and the departure times of their ships.

Began conversations with captains, sailors, and outfitters, and questioned them for information;

Like the ship's name, the identity of its owner, and the date it left New York, everything was written for the Consul Archibald.

In return, Archibald sent Sanchez's classified information across the Atlantic to London and British ships off the African coast.

Thanks to the information that the true owners of the ships are not US citizens, and therefore are not entitled to fly the American flag, the Royal Navy took the necessary measures.

In total, Sanchez's intelligence service canceled 30 slave flights and saved about 20,000 African captives.

The Slave Trade and Civil War

As the slave trade developed in New York, the emerging nation became increasingly divided over slavery.

During a fierce abolitionist dispute in Kansas, a new "Republican" party emerged, led by Abraham Lincoln and William Seward, and was in contrast to the ruling Democratic Party, which supported slavery, and had little interest in ending the illicit slave trade.

Instead of attacking New York, the Republicans kept their harshest criticism of the South.

This was politically appropriate, as a group of southern radicals sought to revive the slave trade on their shores in the mid-1850s, and the Republicans and many Northerners were horrified.

William Seward, a resident of New York, focused on this issue;

Because he believed that "restoring the African slave trade" was a southern priority, a plan that would spread slavery to the expanding western borders.

The writer reported that the Southerners and their Northern allies accused Lincoln and the North of hypocrisy, and asked them to deal with the slave trade, which "takes place before their eyes."

But as the number of slave ships, including the Clotilda, anchored in the South decreased between 1858 and 1860, Republican criticism gained additional strength, and preventing "the resumption of the slave trade in the South" became part of Lincoln's program in the 1860 presidential election.

Trade collapse

When the nation split after Lincoln's election, it was the Confederacy that took the first steps against the slave trade, and recognizing that the issue divided the Confederates at a time when they needed unity more than ever, prominent political figures banned the trade altogether in the Confederate Constitution of 1861.

Lincoln also moved against the trade by allowing the British to inspect American ships through the Lyons-Seward Treaty of 1862, and refusing to commute the death penalty for slave captain Nathaniel Gordon, who became the only American to be executed under the 1820 Act. By 1863, the American slave trade had finally ended.