It is involved in choosing women's clothing and cosmetics

North Korea punishes with "hard labor" those who violate the rules of appearance

The North Korean president visits one of the national cosmetics factories. From the source

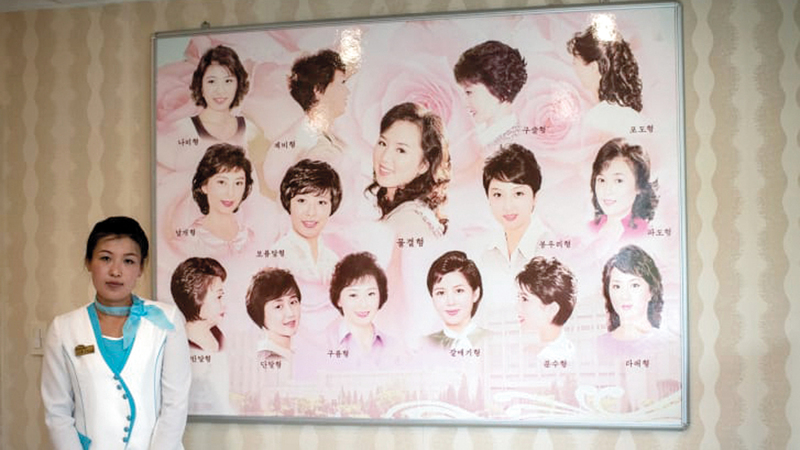

A government crew member stands near a billboard showing what types of hairstyles are allowed. From the source

Black market boom selling contraband cosmetics. From the source

A group of North Korean cosmetics. From the source

picture

The North Korean government bans women from using lipstick because it believes "the color red represents capitalism," says North Korean actress, Nara Kang. She adds, "The government allows most women to put a light dye on their lips, sometimes pink, but not at all red. It also requires them to tie their long hair delicately, or make it into braids."

Kang lives, now, in the South Korean capital, Seoul, where this 22-year-old woman left North Korea in 2015 to escape a system that restricts her personal freedom, starting with what she wears to how to tie her hair.

Before leaving her country, Kang walked through alleys, rather than main roads, in order to avoid confronting "jiochaldai," the North Korean fashion police.

Colors of capitalism

"Whenever I put on makeup," Kang remembers, "the old women in the village would tell me that I was impudent with the colors of capitalism." She adds, "There was a patrol every 10 meters away, to suppress pedestrians because of their appearance." "We were not allowed to wear accessories like this, or to dye our hair, or let it flow," she says, pointing to her silver rings and bracelets, pointing to her wavy locks.

According to two defectors who spoke to CNN and left the country between 2010 and 2015, wearing clothes that are perceived as "very Western", such as: short skirts, shirts written in English, and tight jeans, could expose their owners to fines. Or public humiliation or punishment, although the rules differ from region to region. Other defectors say that some violators are forced to stand in the middle of the town square, becoming the target of severe criticism from officers, and others are ordered to perform hard labor.

"Many women are instructed, or advised, by their families, schools, or organizations to wear respectable clothes and maintain a clean appearance," explains North Korean Studies professor at Korea University, Nam Song Wook. However, Kang says she and other North Korean millennials are still keeping up with fashion trends overseas.

Black market culture, or "jangmadang"

The name "Jangmadang" is given to the local black markets in North Korea that sell everything like fruit, clothes and household products. These markets began to flourish, during the Great Famine of the 1990s, when people realized that they could not rely on government food rations. Many North Koreans still depend on these markets to buy daily necessities, but these markets also remained a source of illicit products and smuggled inside the country, where young people can obtain copies of films, music videos and series, on CDs and memory «Yu SB, or SD cards, were smuggled out of South Korea or China, according to the South Korean Unification Ministry.

"North Korean urban dwellers get their culture from the outside world," says South Korea's country director for North Korea's Human Rights Research and Strategy Group, Seokil Park. Park adds, "This has an effect even on fashion trends, hairstyles, and beauty standards inside North Korea. When North Korean youths watch TV programs in South Korea, they resort to changing their hairstyles or clothes, just as South Koreans do."

Tablets

Before she fled North Korea in 2010, now defector and jewelry designer Jo Yang said she and her friends visited the Jangmadang markets to find USB drives for films and popular music videos smuggled from South Korea.

At this market, Yang says the female traffickers speak the distinct Seoul dialect, to attract the attention of young women who already love South Korean culture. Sometimes merchants would take their customers home, where there were rooms full of contraband clothes and cosmetics. It says South Korean cosmetics are two to three times more expensive than similar North Korean or Chinese products. Sometimes she has to pay the equivalent of two weeks of rice to buy one mascara or lipstick smuggled out of South Korea.

This market is so popular with millennials that it is referred to as "Jangmadang generation," says Park, who produced a documentary of the same name about the lives of North Korean youth and their influence on society. The famine disrupted the education system, so many "Jangmadang" generation grew up in these markets, with more insight into capitalism than previous generations.

Cosmetic industry

Although there are no internationally recognized North Korean cosmetic brands, North Korea's official Central News Agency claims that the cosmetic industry is booming in the country. And in November, Pyongyang hosted a national exhibition of cosmetics, at which it presented "more than 137,000 of these products," including "new soaps to help remove waste from the skin, functional cosmetics (to help) support blood circulation, and anti-cosmetics." Aging », according to the North Korean News Agency.

Homemade cosmetics may be readily available in North Korea, but they are not of the same quality or variety as foreign brands. Park says that women who use contraband foreign cosmetics not only trust local ones, but try to challenge what is prevalent in North Korea. He demonstrates this by saying: "If you wear clothes because you have been influenced by foreign media, you send signals to your community and your friends that you are somewhat different, and ready to break the local rules, which in your view are of no value."

And North Korean culture expert at Dong University, Professor Dong Wan Kang, wrote in a research paper on the topic of South Korea's influence in the northern part, that Pyongyang's attempts to control citizens' personal choices could go to the extreme. "Although the North Korean authorities take strict measures against fashion and hairstyles, for what it calls the decadent culture of capitalism, there is an end to complete control over the desires and needs of its citizens," Kang says in his paper.

South Korean cosmetics are two to three times more expensive than similar North Korean or Chinese products.

According to two defectors who spoke to CNN and left the country between 2010 and 2015, wearing clothes perceived as "very Western", such as: short skirts, shirts written in English, and tight jeans, could expose their owners to fines or Public humiliation or punishment.

Beauty industry as an element in war battle

North Korean President Kim Jong Un established the rules of his rule over the legacy of his grandfather, North Korea’s founder, Kim Il Sung, who established the country's first cosmetic factory in 1949. Song had previously been used by cosmetics to boost the morale of female soldiers in Manchuria. During his battle with Japan, realizing early on the power of beauty to change people's minds, and in his footsteps, the younger Kim invests in cosmetic brands produced by the state, such as: "Bomhyangi" and "Yunhasu" to develop "the best cosmetics in the world."

The recent push for the development of the domestic cosmetics industry comes amid international sanctions, which have made it difficult for North Korea to import high-quality ingredients and products, according to a professor of North Korean studies at Korea University, Nam Song-wook, who says Kim also sees an opportunity for the growing popularity. South Korean beauty products, to produce its own version of Korean cosmetics for export, are inspired by South Korean expertise, in addition to its popular ingredients such as ginseng.

Gleam of hope

North Korea has always had the appearance of its citizens in mind. It banned hair dye, blue jeans and clothing written in English in the Kim Jong Il era, as the reclusive country tried to ward off Western influences. But some observers believe that this pattern has been loosening since Kim took power in 2011, appearing in public with First Lady Ri Sol-ju, a former member of the pop orchestra.

North Korean studies professor at Korea University, Nam Song-wook, says that the young first lady's short haircut and the colorful suits she wears are a sign of a desire for self-expression, given the constraints of North Korean society. "There was no role for the first lady under Kim Jong Il, but her appearance under Kim Jong Un boosted the regime's interest in cosmetics," she says.

"North Korea is a tightly controlled society, and the approach we can follow is very limited, and the first lady is an example that we can follow," Kang says.