During the past few years, the idea of eliminating the manifestations of colonialism gained a new political momentum within the borders of the old colonial countries.

Just as movements representing indigenous peoples regained the mantle of fighting colonialism, protests arose in the United States and others in Britain, as South African students studying in the United Kingdom marched on the slogan of decolonization in the European curriculum.

Writer and author Adom Getachew - in an article for the American New York Times - believes that museums such as the Museum of Natural History in New York and the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Brussels have been forced to rethink the way in which the colonized African peoples and indigenous peoples are presented.

But what does eliminating colonialism mean? The author wonders explaining that the meaning of this phrase and what it requires has been the subject of controversy for a century, as the struggle against colonialism in the twentieth century was not only about obtaining political independence, but rather it was about breaking the global hierarchies that subjugated the global south in pursuit of a world dominated by equality for all. .

History of Independence

After the First World War, the view of European colonial officials for decolonization was that it was a process by which they would allow their colonies to be independent after following the model of European countries.

But in the mid-twentieth century, anti-colonial activists and intellectuals demanded immediate independence, and refused to form their societies according to the conditions set by the imperialist colonialists.

And between 1945 and 1975, and in light of the victory of the independence struggles in Africa and Asia, the membership of the United Nations grew from 51 countries to 144, and decolonization in that period was primarily of political and economic dimensions.

With more colonies gaining independence, the elimination of cultural colonialism assumed greater importance. The political and economic hegemony has accompanied European centrality, which values European civilization as the pinnacle of human achievement.

Colonialism abused cultural traditions and indigenous knowledge systems, and considered their culture backward and uncivilized, and colonized peoples were treated as peoples with no history. The struggle against this cultural dispossession has been particularly pivotal in colonies that are being settled, as indigenous people and their institutions are violently displaced.

A renewed struggle

The writer pointed out that the features of that era of anti-colonial struggle are now returning with the protests sweeping the world led by the "black lives matter" movement, as calls have been raised to eliminate the manifestations of colonialism in the former imperial capitals in Europe.

In Bristol, England, last month protesters smashed a statue of Edward Colston, director of the Royal African company that dominated the African slave trade in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In Belgium, protesters focused on targeting statues of King Leopold II, who ruled the Congo Free State (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and managed things in it as if it were some of his personal property from 1885 to 1908.

Recently, King Philip II of Belgium lamented the brutal regime of his predecessors, which caused the deaths of 10 million people.

Colonialism and the Modern World

The protesters believe that colonialism not only constituted the southern part of the world, but shaped Europe and the modern world as it is now. The proceeds of the slave trade fueled the rise of seaside cities such as Bristol, Liverpool and London, while the transatlantic economy - created by slavery - helped in Feeding the Industrial Revolution.

By demolishing or distorting statues that immortalize the symbols of that era, the protesters were able to open the debate about reconsidering the national narrative about them, and imposed a confrontation with the history of imperialism, which the author considers a form of eliminating colonialism in the sensual world, and shattering the illusion that imperialism was elsewhere .

The article pointed out that this historical review was only the first stage in the course of eliminating colonialism, while the second stage paved the way for it to recognize the responsibility of colonial history for shaping the social, economic and class inequality that characterizes the world today, and then reparation and restitution of rights.

The author concluded that the struggle for racial equality in Europe is a struggle to truly reach post-colonialism, and that the chances of this succeeding are enhanced every time a statue is removed from its pedestal. If colonialism contributed to the formation of the modern world, its elimination would not be complete unless the world, including Europe, was reshaped.

Post-Empire

In her book “Making the World After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination,” Getachew argued that the experience of decolonization revolutionized the international system during the twentieth century. However, standard histories presenting the end of colonialism as an inevitable transition from a world of empires to a world of nations, a world in which self-determination was synonymous with nation-building, obscure how drastic this change is.

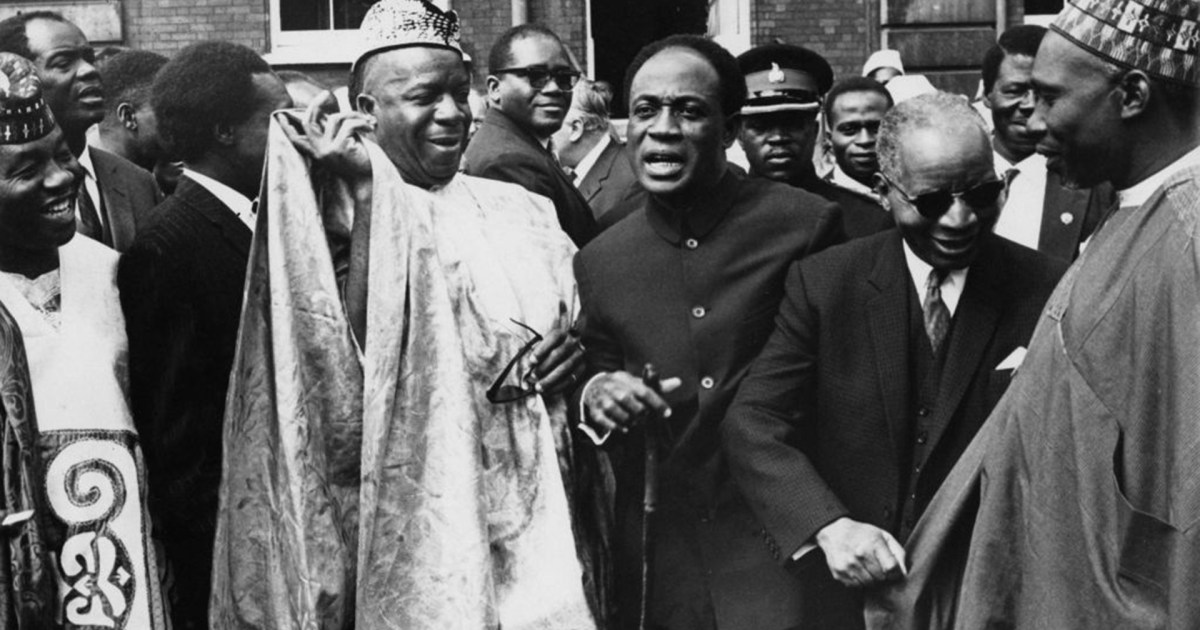

The author is based on the experiences of political thought of anti-colonial intellectuals and statesmen, such as the Nigerian Nnamdi Azikiwe, the American sociologist Webb De Bois, the Pan-African movement activist George Badmore, the freedom fighter and the first president of independent Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, the Jamaican militant Michael Manley, the Tanzanian Julius Nyerere, and others .

The author argues that these leaders sought to build an international legal framework for non-dominance, through collective action aimed at shaping the rules of the global economic game. For these leaders, self-determination requires transcending formal political equality in the international sphere.

However, because of the contradictions inherent in projects such as regional political unions and the new international economic order, and because of the opposition of Western capitalist countries; Their efforts ultimately failed.

The book considers that African nationalists and activists of what the author calls the "Black Atlantic" (West Africa and the Caribbean), anti-colonialists, formulated alternative visions for world industry in pursuit of creating a post-imperial world based on equality, and tried to transcend ethnic, legal, political and economic hierarchies by securing The right to self-determination within the newly established United Nations, the formation of regional federations in Africa and the Caribbean, and the creation of a new international economic order.