The Russian war in Ukraine wasn't the first major geopolitical event that took place on social media in parallel with events on the ground.

It started with the Arab Spring in 2011 via Facebook and Twitter, while clips of Syrian children suffocating with chemical weapons filled social media in 2018. These platforms also reported the facts of the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul, and the chaos of the American withdrawal, through live tweets that found their way to our homes last year.

But the current conflict is an entirely different generation of social media wars, fueled by TikTok's transformative impact on age-old standards of technology.

TikTok has produced a series of war shots we've never seen before, from grandmothers saying goodbye to sons and grandsons to instructions on how to drive captured Russian tanks.

A large part of Tik Tok's success is due to its reliance on visual content, in addition to its ability to convey developments moment by moment.

So, with Russia ready to go to war with Ukraine, the site has turned into a boon for open source investigators trying to track troop movements and developments in the war moment by moment, prompting some to dub the Russo-Ukrainian war “wartok.”

While Facebook and Instagram put limits on the sharing of aggressive shots, and YouTube requires a load of equipment and a lot of time to edit videos, TikTok is fast, instant, and avoids all those drawbacks.

And as anyone who has surfed social media in the past week knows, what happens on TikTok rarely stays on TikTok, as it spreads to other apps at breakneck speed.

“As an analyst of what is happening in Ukraine right now, I get 95% of my information from Twitter. Before that, it was 90%,” says Ed Arnold, Research Fellow in European Security at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). Some of your information comes from official sources, such as intelligence sources."

But while surfing Twitter, Arnold noticed a strange trend: a large portion of the videos shared are emblazoned with the TikTok watermark.

(1)

Arnold explains this shift by saying, “It makes sense… Tik Tok is ubiquitous, easy to use, and used by a lot of young people,” which the statistics seem to support.

As of July 2020, 28.5 million people out of 144 million people in Russia have used TikTok (1), and we can expect a similar percentage of users in Ukraine at a bare minimum.

fierce algorithms

Providing you with relevant content on the For You page is the main work of the TikTok algorithm, which can catapult someone to stardom overnight, and also means that shaky snapshots of the aftermath of a Russian missile attack can be viewed by millions of people within minutes of downloaded.

(2)

The TikTok algorithm feeds attention-grabbing videos with its famous feedback feature, which simply works as follows: “If there is more video demand, we will raise the profile, surely there are a lot of videos about the war right now. The eight days between February 20-28, video views tagged with #ukraine jumped from 6.4 billion to 17.1 billion, an average of 1.3 billion views per day, or 928,000 views per minute.(Content tagged with #Украина, Ukraine in the Cyrillic alphabet Which includes Russian, Ukrainian and others, is almost equally popular, with 16.4 billion views as of February 28.) (1)

Many of the most viral Ukrainian videos were shared on TikTok by Marta Vasyuta, a 20-year-old Ukrainian girl currently residing in London.

When the war began, Vasyuta found herself stuck abroad, and decided to turn her TikTok profile, which only had a few hundred followers, into a platform for sharing footage of the conflict with the wider world.

“If you post a video from Ukraine, it is likely that only Ukrainians or Russians will see it,” she says.

This anomaly is a result of how TikTok often localizes videos shown on each person's For You page.

Hoping her London post could help Ukraine clips avoid the algorithm, Marta started posting until she was banned late last week, something she believes may have been due to mass reporting of her profile by Russian bots after she gained 145,000 followers.

(A message from TikTok shows that Vasyuta is temporarily banned from posting three videos and one comment that violated the platform's community guidelines. TikTok did not respond to a request for clarification on the rules that were violated.)

One clip shared by Vasyuta, which shows the barrage of bombs on Kyiv, has been viewed 44 million times on TikTok, and has been shared off the app nearly 200,000 times.

It's hard to know where he's gone, the way you share on TikTok doesn't allow you to trace a video back to its source.

But that speed and reach on and off TikTok comes at a price, as inaccurate videos can quickly spread misinformation.

From the small screen to the screen of our phones

This is clearly visible in a video that shows a soldier in military fatigues, gently heading to the grain fields below with a broad smile on his face.

But the video, which was posted on TikTok and reshared on Twitter, garnered 26 million views on the app and claimed to be a recent clip from the Ukraine war, dating back to 2015, was originally posted on Instagram.

In order to get around this issue, TikTok has partnered with independent information verification organizations in an effort to combat the spread of misinformation, but previous research has shown that fake news travels six times faster than legitimate information on social media, in large part because to its ability to elicit a powerful emotional response.

The problem is that Tik Tok was designed primarily to flood its users with this hijacking content with strong emotional effects.

(3)

“It's called crowdsourcing," says Claudia Flores Saviaga, who studies disinformation, crowdsourcing and social computing at Northeastern University. "It's very normal during crises like wars or natural disasters."

By using tools that allow everyone to post videos without investigation, TikTok helps create false mass awareness through widespread distortion of facts.

So far, pro-Ukrainian profiles dominate the discourse on TikTok, but Russia may not mind the spread of clips of destruction in Ukrainian cities, serving its own psychological warfare goals.

"Social media is certainly being weaponised," warns Saviaga. "This includes disinformation or distortion, designed either to intimidate or take advantage of the massive appetite for war content."

From fake live broadcasts to video game clips repurposed as footage on the ground of invading forces, TikTok is under scrutiny and criticism for its inability to censor content.

The non-profit Media Matters for America has highlighted numerous cases of amplifying and promoting false content via the app.

(4) For its part, TikTok spokeswoman Sarah Moussaoui responded by saying that the company continues to “monitor the situation with increasing resources to respond to emerging trends and remove offending content, including harmful misinformation and promotion of violence,” but failed to give specific details.

(5)

digital war

In Concerning Others' Pain, 2003, American author Susan Sontag traces the evolution of war journalism from photography to television.

The Spanish Civil War was marked by the emergence of a professional photojournalist equipped with professional lenses, while the Vietnam War was the first to be televised and the massacres made a major guest in homes on the small screen.

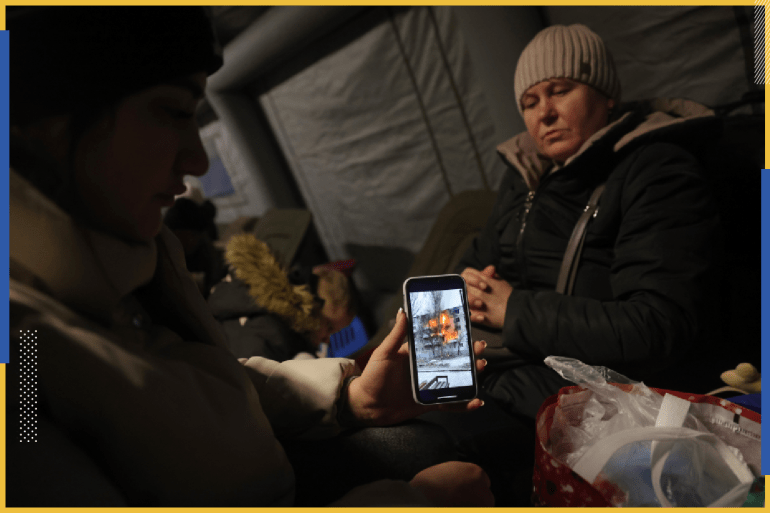

Now those little screens are our phones instead of TVs, and footage of war takes its place in the midst of our 24/7 feeds, along with our discussions of our favorite TV series finale, cute animal portraits, and updates about other contemporary disasters.

The various forms of content confusingly overlap, the professional with the amateur, the intentional with the casual.

A woman gives birth while sheltering in Kyiv metro station, and elsewhere on the metro, families gather with cats and dogs, a Ukrainian father bids farewell to his family in tears, a tractor pulls an abandoned Russian tank, and a British man records a video of himself packing to go to Ukraine saying he is doing it “to save his wife and son."

Together, these excerpts provide a montage of life in wartime.

Ukrainian President Zelensky himself has cleverly exploited the situation, captivating the world with personal videos from the heart of the street.

Ultimately, the purpose of war photojournalism remains to provide the private testimony of the photographer, journalist or layman at the moment, but it is up to the viewer to interpret what he sees in the resulting images.

As Sontag writes, “Photographs of atrocities may lead to conflicting responses: a call for peace, a cry for revenge, or perhaps simply a bewildered realization from the never-ending accumulation of horrific images and videos.”

———————————————————––

Sources

Tiktok was designed for war

Inside TikTok's latest big pitch to advertisers with new numbers showing time spent on the app and engagement metrics

Fake news travels six times faster than the truth on Twitter

TikTok is facilitating the spread of misinformation surrounding the Russian invasion of Ukraine

Russian-based disinformation about Ukraine is spreading through major social media platforms