The Algerian writer Samir Kassimy (1974) is considered one of the most prominent new Algerian novelists, and his works favor experimentation and rebel against the authority of the traditional novelist model.

In this dialogue, Samir Kassimy says that the Algerian novel is not present in the Arab cultural scene in the way we like, describing Arab criticism as "unjust".

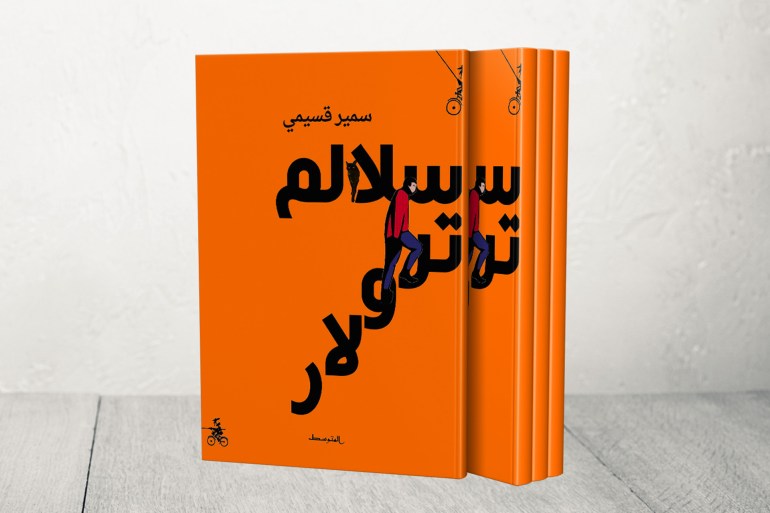

Qasimi has nine published novels, including: "The Dreamer", "A Wonderful Day to Die", "Halabel", "Love in a Leaning Autumn", "In Love with a Barren Woman", "Declaration of Loss", and "Foolishness as Never Someone Tells It”, and “Trollar’s Ladders”, and these novels delve into the concerns of the marginalized, and the foggy political reality in our Arab world in general and his country, Algeria in particular.

In his novel "In the Love of a Barren Woman", he raises the problem of the relationship between the citizen, the homeland and the ruling authority.

His novel "Declaration of Loss" is considered the first Algerian novel that deals with the prison in all these details, for the Algerian El Harrach prison and its inmates, although Kassimi refuses to classify it within "prison literature".

The novel “The Dreamer” deals with a question, as much as we think its answer is easy, as much as we discover its difficulty, which is: Is the dream worth sacrificing everything for it?

The novel attempts to answer this question in an answer that combines exoticism and reality.

Qasimi writes at any time, as he does not have a special writing ritual, although one of his priorities is to make every effort to provide interesting writing that is worth the reader's money and time.

In this dialogue, Samir Qasimi talks about his novels, about the novel in general, and about criticism, criticism and writing.

You have stated in more than one dialogue that you write for pleasure, and that you may write to suppress your feeling of dissatisfaction every time you release a work.

After all these responses, do these answers still exist?

Everything I stated is true in some way, at least it was true when I stated it. Writing is not an exact science. One of us can claim that he knows the answers or does not know them based on his experience or ability to them. In fact, as I get older, I experience strange feelings that all intersect with Doubt, not in what I write or write, but in the usefulness of writing, and in my ability to continue with it.

I think this doubt also has something to do with the environment in and about which we write.

Of course, I can't speak in someone else's tongue, but I no longer believe in the existence of any pleasure in writing, it is hard work that does not result in any compensation in its level, but I began to believe that it is a craft as much as its owner is good at it, as much as he increases his humility in front of her to admit that he did not add anything worthy of the age he spent. spent in it.

Now, after more than a decade and a half of writing, and after about ten novels, I can say that I do not write in search of anything, even myself I do not search for it through my novels. What self would we dare to search for in a society that does not allow its independence or its difference from it?

The novel "Trollar's Ladders" creates a parallel reality from a satirical epic facing politics (Al-Jazeera)

Why do you write then?

Perhaps because I promised my mother when I was young that I would be distinguished from all my brothers, and I tried to fulfill my promise, but it seems that I did not succeed in the way that excellence means, of course. Except for my mother's face.

I remember the day I started writing my first novel, “A Permission to Lose.” After the first line, I decided to give this face the space it deserves, but I could not, then I repeated the attempt in the novel “The Dreamer” without success.

I was fascinated by two thoughts that continue to haunt me every time I try to write something: death and failure.

Now that I have nine published novels and one waiting to be published, I can admit that they are the same idea that animates me disgustingly, to make me admit that I write just for the sake of time, under the illusion that I am alive or that I have not failed yet.

But your works do not only deal with death, along the lines of “A Wonderful Day to Die.” In “Declaration of Loss,” you dealt with prison in the first Algerian novel dealing with life in prisons, and in “Halabel” you wove a parallel history for marginalized peoples by making them the descendants of an imaginary (marginalized) brother of Cain and Abel. And in “The Love of a Barren Woman,” she addressed rape, not only as a physical reality, but also as a state of mind experienced by a marginalized community?

It is undoubtedly true, but you will not find a single novel in which I managed to get rid of the ideas of failure and death. Rather, they are, in addition to chance, what makes the narrative line the most in all my works.

The novel "In the Love of a Barren Woman" tells about the abhorrence of "the Compulsory Homeland" (Al Jazeera)

At least, this is what I see whenever I read my previous works, and the only exception may be the novel "Love in a Tilted Autumn", which was wronged by Arab criticism by ignoring it or describing it as a sexual novel, as much as Western criticism after it was translated into French and its critics were able to Realizing the purpose of using sex in her, to return, strangely, to the same Arab criticism to praise her again after he slandered her.

Referring to your novel "Love in a Tilted Autumn", you dealt with issues such as love and sex, faith and atheism, politics and history, death and annihilation, and the isolation of man in today's world.

Through these signs, what idea did you want to convey to the reader at the moment of writing?

It is the very thought that we try to capture in life, for you to say a foolish desire to encompass a question that haunts us all: “Why are we here?”, on this very earth, in this age alone?

Is it really for God to test us and worship Him, or to leave a trail, or is our existence mere vain, with no purpose other than existence itself?

I realize that the heavenly religions and other earthly philosophies that are called religions, give us more than one answer, and some even forbid such questions, but I think that they are questions that every one of us has.

There is a delicious feeling that every one experiences on this earth, even for a few and rare moments in his existence, that makes him imagine that he is the center of the world, and it is a feeling I wish we had all our lives, at least the purpose of existence becomes separated in it, but unfortunately it is a temporary feeling that is not real, except in the context What I wanted from the novel, which is that the purpose of any one of us is to find a way to become the center of someone else's existence.

I did not find - after long reflection and contemplation - nothing but "love" to be the reason for this perception or feeling, so I chose two characters in their late lives arguing about the idea: "Does love have a specific age, or can it fall in love and a person can live it at any age?"

Unfortunately, after the publication of the novel, and the harm caused to it by the sexual scene in the first chapter, I discovered that we are not ready for such an intellectual and contemplative dialogue in our Arab narration. , made us witness hybrid types of narrative writing similar to the linguistic novel, as well as what is called the “moral novel”, without forgetting what we call the fallacy of the “historical novel”, which is not so, as long as it does not depend on the writer’s imagination and his employment of history, but rather on the insertion of history. Update an event in a pre-configured template, which is unfortunately encouraged by some publishing houses that form "lobbies" with certain prizes.

Everyone remembers the farce that took place in one of the Arab awards claiming the description of universality, when every non-historical novel that does not address in some way the vilification of the Turks was rejected, for reasons and motives that do not deserve the effort of detailing them.

Which of your books do you have a close relationship with?

There is no, only the text I am about to write, and as soon as it is printed and issued, this relationship is cut off.

In your novel "The Folly as Nobody Sees It", we notice that you created a dark world, through which you presented a severe criticism of our Arab reality.

Political and social events often push the intellectual to take moral positions.

What is its impact on reality?

"The Folly Like No One Told" is included in the framework of a project that I finished with her, which she started with "Trollar Ladders" to form with "The Folly as No One Has Seen It" - because it includes two novels: "The Foolishness of the Duke de Carre" and "The Fool Always Reads" - a trilogy located It takes place in Algiers, on 3 very popular streets: Trolar, Duke de Carre, and Rue Dr. Saadane.

It is a trilogy that deals with the political, historical and social absurdities that Algeria, as well as the Arab world, lived through.

But once again, she does not feel that the Arab critic has any desire to receive reality as it is in its cruelty, injustice, taboos, and immorality as well, and not as he wants, a reality that is beautified in some way, and he has no ability to adopt experimental works outside the norm.

That is why I was very happy when the Egyptian novel, Tariq Imam, gained the popularity it gained when the reader spontaneously adopted it.

This time, a novel of this kind has escaped to this list, but I will not be optimistic to hope that the award will open its doors for different writing in future sessions, unless I rethink the mechanism of selecting the arbitrators.

The novel "Insanity as no one has seen it" is a satirical work that digs into the conscience of the absurd and intersects the political with the social (Al-Jazeera)

Did you want through the novel “The Foolishness as No One Sees It” to present life in a great scene that cares about man, his crises, his problems and his obsessions?

This is a great goal that only a narcissistic or delusional writer will claim for the world, but my goal was what I mentioned before, in addition to writing a different novel that achieves fun and it has been achieved.

I think that when it is published in French, translated soon by the publishers of "Acts Sud", the Sinbad series, it will occupy the real criticism in another way, just as it happened to the novel "A Wonderful Day to Die" and "Love in a Tilted Autumn" when they were translated.

Do you have your own rituals for the moment of writing?

I had it, but I could not keep it. It is difficult for the Algerian writer to keep anything, he does not keep his work or his family, and sometimes - which is the norm - he does not keep his principles and positions, so how does he keep his rituals?

Personally, my priority is to preserve my ability to write interesting and my attitudes, which, even if it cost me the loss of my work, has earned me more and more self-respect and the respect of my readers for me, and most importantly the respect of my wife and children, so it does not matter if I lose meaningless things after my death, preserving what is most important as I said.

How much does the reader preoccupy you?

Frankly, it does not concern me completely, all that concerns me is my text, as it is enough that it is good for any reader to like.

In your novels "Declaration of Loss", "A Wonderful Day to Die", "In Love with a Barren Woman", and "Trollar's Ladders" are realistic projections of what is happening in your country.

Can we call the events that occur in your works history with a fictional form?

Classification is not my job, I'm a novelist who writes texts only, and he only cares about them being worth the reader's money and time.

In general, as a journalist and novelist, how do you read the presence of the Algerian novel in the Arab cultural scene?

It's not present in the way we like it, but I hope it will happen soon.

What is your concern today?

What preoccupies me and preoccupies me always, I mean life and nothing else.