On March 26, 1664 (some sources indicate March 27), the Poles executed the former Little Russian hetman Ivan Vygovsky. According to experts, this historical figure, who repeatedly betrayed his oath, provoked a brutal civil war on the territory of modern Ukraine and was one of those who laid the foundations for the split between its western and eastern lands.

From captivity to dictatorship

Ivan Vygovsky came from an Orthodox noble family who lived in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Where and when the future hetman was born is unknown. However, historians claim that in his youth he received a good education, after which he enlisted in the Polish army. According to one version, he rose to the rank of cavalry captain, according to another, he was a clerk under the Polish Cossack commissar. His career was interrupted by the defeat of the forces of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from the rebel army under the command of Bohdan Khmelnytsky at the Battle of the Yellow Waters in 1648. Vygovsky was captured by the allies of the rebel Cossacks - the Crimean Tatars.

“Bogdan Khmelnitsky bought Vygovsky from the Tatars. Many sources write that his payment was a horse, but this is most likely just a legend that arose when Vygovsky had already become a traitor in order to humiliate him. The Tatars would not have sold the captain so cheaply. Vygovsky, apparently, was needed by Khmelnitsky to establish control structures in his army. Many ordinary people took part in the uprising, but there were not enough skilled administrators, business executives, and members of special units. Khmelnitsky, apparently, previously knew Vygovsky well from a professional point of view and highly valued some of his qualities,” Vladimir Volkov, a professor at Moscow State Pedagogical University and the Russian Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, noted in an interview with RT.

Painting by Alexey Kivshenko “Pereyaslav Rada. 1654 Reunification of Ukraine"

© Public domain

After some time, Vygovsky took the position of general clerk of the Zaporozhye army. Historians equate this post to the modern position of the head of the country's government. Moreover, Vygovsky secretly sent Khmelnytsky’s correspondence with the heads of neighboring states to Moscow, thus helping to control the hetman, for which he received rich gifts. He became a large landowner, whose estates even included two cities: Oster and Romny. It seemed that against the backdrop of the annexation of the lands of the Zaporozhian Army as a result of the Pereyaslav Rada to Russia, Vygovsky found himself in an advantageous position. However, this was not enough for him.

When Khmelnitsky, due to health reasons, realized that his days were running out, he decided to declare his son Yuri as his successor, but learned that Vygovsky was also dreaming of the hetman’s mace. As a result, Khmelnitsky ordered his clerk to be shackled and kept facing the ground. Vygovsky desperately repented, and the leader of the Cossacks forgave him.

However, as soon as the hetman died, Vygovsky held a council, to which he invited only representatives of the elders loyal to himself. He did not notify the Zaporozhye Sich and did not wait for political opponents from among the Cossack colonels. As a result, representatives of the inner circle in a narrow circle proclaimed Vygovsky the new hetman.

Having come to power, Vygovsky began to intrigue, entering into separate negotiations with Sweden and the Crimean Khanate. He did not dare to openly speak out against Moscow right away, but spread false and absurd rumors: supposedly the Russian authorities would ban the production of alcohol on their own and would drive everyone into taverns, or the Russian Tsar would force the entire population of Little Russia to wear black boots.

“Vygovsky launched repressions. Strengthening his power, he executed or sent into exile unwanted Cossacks and their families,” Artyom Barynkin, associate professor at St. Petersburg State University, said in a conversation with RT.

While Moscow was understanding what was happening on the banks of the Dnieper, Vygovsky, with the help of the Crimean Tatars, eliminated the colonels who were in opposition to him. In particular, he defeated the forces of Martyn Pushkar. And dissatisfied with the actions of the hetman, Vygovsky gave Poltava and Mirgorod to the troops of the Crimean Khanate for plunder.

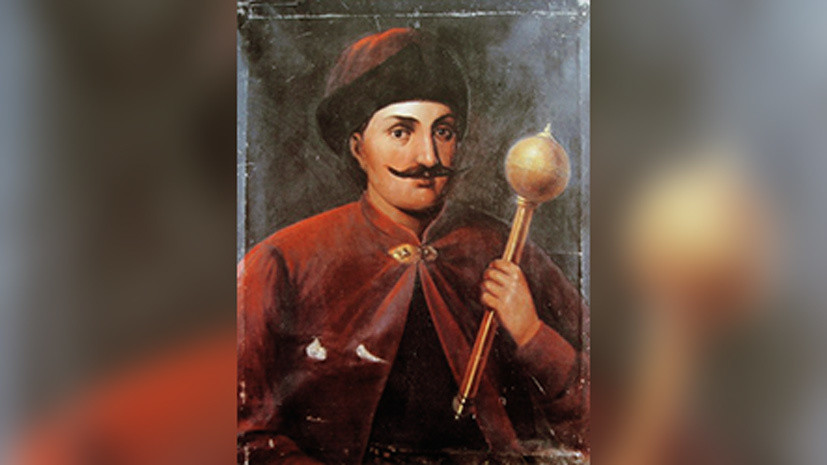

Portrait of Hetman Ivan Vygovsky (artist Vasily Dyadinyuk)

© Ukrainian Nation Museum

Poltava, which had not known war for many years, found itself in a terrible situation. Vygovsky's allies engaged in mass robberies and murders, burned houses and raped women. This lasted four days, until even the Cossacks who supported Vygovsky himself began to be indignant. Some researchers count the period of the so-called Ruins - desolation and civil wars that lasted on the banks of the Dnieper for about 30 years - precisely from the hetman’s victory over Pushkar and the destruction of Poltava and Mirgorod.

“While Vygovsky, guided by opportunistic considerations, believed that it was beneficial to be friends with Moscow, he demonstrated fidelity and loyalty to the tsar. When he decided that he had reached a new level of independence and could get something more from Poland, he switched sides,” said an employee of the Center for Ukrainian and Belarusian Studies at the Faculty of History of Moscow State University in an interview with RT. M.V. Lomonosov Associate Professor Dmitry Stepanov.

“I forgot about my previous vows”

On September 16, 1658, Vygovsky signed the Gadyach Treaty with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, according to which all of Little Russia came under the authority of the Polish king, and the so-called Grand Duchy of Russia was proclaimed on its territories. The Cossack elders received equal privileges with the Polish gentry, and the Orthodox clergy received freedom of worship. The size of the Cossack register was set at 60 thousand people, but Vygovsky, during secret negotiations, immediately agreed to reduce it by half.

According to historians, many Cossacks remembered what the previous agreements signed with the authorities of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were worth, and understood well that with the arrival of Polish troops, most rights and privileges could be forgotten. But Vygovsky was attracted by the prospect of equal rights with the Polish aristocrats.

As Artyom Barynkin noted, the current situation pointed out to Vygovsky the benefits of cooperation with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but he was not distinguished by his principles.

“Vygovsky was an Orthodox Rusyn, brought up in the Polish mentality, Polish legal and cultural tradition. He admired everything Polish. But for the Poles, despite belonging to the gentry, because of their religion, people like him remained third class. But the Orthodox gentry did not want to convert to Catholicism. As soon as the Polish authorities gave Vygovsky guarantees of equality, he forgot about all his previous vows and oaths,” explained Vladimir Volkov.

After the signing of the Gadyach Treaty, Vygovsky launched military operations against Russia and the Zaporozhye Cossacks loyal to Moscow. In 1659, the Battle of Konotop took place, which modern Kyiv politicians are trying to present as “the victory of the Ukrainian Cossacks over the Russian army.” However, this interpretation is fundamentally incorrect. Vygovsky’s Cossack regiments, uniting about 16 thousand people, supported the Crimean army of up to 35 thousand. In addition, Polish-Lithuanian mercenaries, who numbered up to three thousand, acted with them. There were only about 28-29 thousand Russian and Cossack forces loyal to the tsar in the Konotop area. And a detachment of six thousand under the command of Prince Semyon Pozharsky, who became carried away in pursuit of the enemy and was ambushed by troops of the Crimean Khanate, was defeated. Pozharsky himself was captured and executed by the khan after he publicly called Vygovsky a traitor. The main forces of the Russian troops retreated from Konotop so as not to leave enemy forces in the rear.

Mounted warrior of the Polish-Lithuanian state, 17th century

© Public domain

The battles near Konotop turned out to be Vygovsky’s last serious political success. Dissatisfied Cossacks began to revolt against him en masse. Some of the rebels declared Yuri Khmelnytsky as hetman in Bratslav.

Having completely lost popular support, Vyhovsky was forced to hand over the kleynods (symbols of the hetman’s power) to Khmelnitsky the Younger and, fleeing from his former subordinates, fled to Poland. There he was first received warmly, formally appointing him as Kyiv governor and declaring him a state senator. However, Vygovsky was let down by his penchant for intrigue.

Yuri Khmelnitsky soon left his hetman post and became a monk. In Little Russia, a fierce struggle for power unfolded between various elder groups. Vygovsky entered into correspondence with some Cossacks still loyal to him in the hope of again competing for the hetman’s mace. But the Poles did not want to anger the more powerful representatives of the Cossack elders, who could connect Vygovsky’s actions with the official position of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The ex-hetman was reminded of his past sins and was shot on March 26, 1664.

On February 9, 1667, the Truce of Andrusovo was concluded between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, according to which Moscow received Smolensk and the Left Bank of the Dnieper. The lands of modern Right Bank Ukraine went to Poland, and remained under its rule for more than a hundred years.

“The main result of Vygovsky’s activities was the offensive of the Ruin, and the division of the future Ukraine into West and East that arose largely because of it. There are still serious cultural differences there. Vygovsky’s role in East Slavic history can be called tragic,” summed up Dmitry Stepanov.