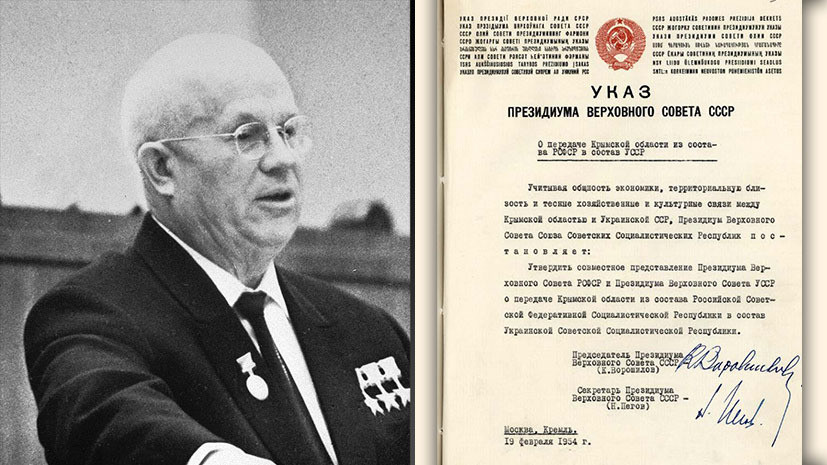

— On February 19, 1954, the Crimean region was transferred from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR. To what extent was the legal procedure for the territorial reassignment of regions of the USSR observed during the transfer of Crimea to Ukraine? Can we say that it was completely legitimate?

“We carefully studied these materials during the preparation of proposals for holding a Crimean referendum on the return of Crimea to the Russian Federation and did not find any more or less sane argument justifying this transfer. No logic. Justifying this act on economic issues is completely stupid, because at that time there was a single country and the development of a particular region was carried out in a single field, republican affiliation had nothing to do with this.

Judging by how hasty and non-public the decision was, there was an understanding of the illegitimacy and unpopularity of this process in the actions of the Soviet leaders. Apparently, they could not do this legally or did not have time, and therefore they piled up such legal blunders that one is amazed. They latently suspected that they were opening Pandora's box, but for some reason they really wanted to carry out this process, so they did everything behind the scenes. We assess this act as chaotic, voluntaristic, and, by and large, politically stupid.

Chairman of the State Council of the Republic of Crimea Vladimir Konstantinov

RIA News

© Konstantin Mikhalchekvsky

— Was the status of Sevastopol agreed upon during the transfer of Crimea in 1954?

- No. In this rush, they did not bother to stipulate the status of Sevastopol, so it was simply assumed after the fact that Sevastopol was transferred along with the region. It turns out that the Ukrainian SSR received not even a region, but the entire peninsula. In Soviet times, all this did not matter much, but with the proclamation of independence by Ukraine, it turned out that Sevastopol was also a Ukrainian city. For example, the documents on the presence of the Russian fleet in Sevastopol stipulated that Russian ships must request from the Ukrainian coast services the right to enter and exit the bays of Sevastopol. And during the time of Yushchenko, more precisely, during the events in South Ossetia in 2008, the Ukrainian side tried to take advantage of this right. Then, let me remind you, military operations against Georgia were also carried out by ships of the Black Sea Fleet. And Yushchenko tried to put a spoke in their wheels in various ways.

So, as far as I know, there were no specific documents on the transfer of Sevastopol. But in that bacchanalia of lawlessness no one paid attention to this.

Sevastopol from a bird's eye view

RIA News

© Alexey Malgavko

— There are several versions of the reasons for the transfer of Crimea to Ukraine. Among them are the acceleration of the post-war restoration of the peninsula, and a change in the ethnic composition of Ukraine towards an increase in the share of the Russian population, and Khrushchev’s desire to enlist the support of the Ukrainian nomenklatura in his struggle for power with Malenkov. The only thing that is not in doubt is the fact that this was Khrushchev’s sole decision. From your point of view, what motives were the first secretary of the CPSU Central Committee actually guided by?

— The version about some kind of acceleration of the restoration of Crimea by transferring it to the Ukrainian SSR was invented by Khrushchev’s son-in-law Alexei Adzhubey as a kind of justification for his father-in-law’s extremely unpopular decision. If we talk about socio-economic reasons, then besides the construction of the North Crimean Canal within the framework of one union republic, there are simply no others. But this argument, so to speak, floats shallow. For example, in the late USSR, a gigantic project of turning Siberian rivers to the south - towards the Aral Sea - was maturing. So what, Siberia should have been annexed to Uzbekistan?

Yes, the main highways leading to Crimea entered the peninsula from the north, from the territory of the Ukrainian SSR, but many of them began outside of Ukraine. For example, the railway, which connected Simferopol with Moscow at the end of the 19th century, passes through Kharkov and Zaporozhye. And what is the conclusion from this? None.

All these versions appeal to the consciousness of post-Soviet people, when the USSR collapsed into independent states. But until 1991, all this was a single national economic complex, and it was in this form that the economic development of the USSR took place.

I think the determining factor in the decision was what then became firmly attached to the characterization of Khrushchev’s management style as “voluntarism.” So he wanted to give something to Ukraine for the anniversary of the Pereyaslav Rada - Crimea turned up: take it, the state will not become poorer! Naturally, in parallel there was a bribery of the top officials of the Ukrainian SSR, which was necessary, since Khrushchev was not then the undisputed sole ruler of the Soviet Union, he still had to fight to establish his unconditional leadership.

To justify Khrushchev, we can say that the transfer was carried out within the framework of a single state and for many it seemed like a kind of mechanical process: like transferring something from one pocket to another pocket of the same trousers. It is possible that this is precisely why during the transfer process blatant violations of the then legislation were committed, making this act itself a fiction in the legal sense.

— It is known that the first secretary of the Crimean regional committee of the CPSU, Pavel Titov, spoke out against the decision to annex Crimea to Ukraine, but it seems that there were no other votes against it. How did the Crimeans perceive this resubordination in 1954? Were there anyone who disagreed with Khrushchev's decision? Was there any opposition to the new administrative subordination in Crimea? If yes, how did this manifest itself?

— Crimeans responded to this decision with dull dissatisfaction. It intensified when Crimea experienced the first waves of Ukrainization. And they covered us long before Ukraine gained independence. But the main thing is the feeling of injustice that has happened. Almost all Crimeans who survived this transfer, as well as their descendants, who inherited the same attitude towards this act from their parents, spoke about this in conversations. The fact that in those harsh times anyone even indicated their disagreement with governing decisions is in itself surprising and remarkable. But, for obvious reasons, there could not be many direct oppositionists: less than a year had passed since Stalin died, and the entire repressive machine he created was still in perfect order and on the move.

I do not know about any facts of organized resistance, but the mood of rejection was general throughout the 60 years of existence of this misunderstanding. For example, my entire childhood was spent in debates and discussions about the transfer of Crimea to Khrushchev, especially when he himself was displaced. All this was actively discussed at the everyday level in Crimea, but there were no protests. There couldn't be any. There was a single country, just emerging from the Great Patriotic War, which was busy restoring the national economy, which completely trusted its leadership. Therefore, people accepted and accepted any decision, even if they didn’t really like it. But resentment and a sense of injustice never left the Crimeans.

View of the city of Sevastopol, 1991.

© D. Chernov

And when perestroika broke out, the political activity of Crimeans immediately brought to the fore the topic of restoring historical justice. This resulted in the first Crimean referendum, which allowed us to restore the republican status of Crimea. But in the first half of the 1990s, no matter how much I wanted, it was not possible to return home. Although Crimea then passed its part of the way towards Russia. But Putin was not the president of the country at that time, so we had to postpone our return for a couple of decades.

For me, as well as for the Crimeans, it is obvious that this was our common dream, the Crimean idea, if you like. It united several generations of residents of the peninsula. And we managed to implement it. You can imagine how happy this is for us.

— Have there been any changes in the lives of Crimeans as a result of the inclusion of the region into the Ukrainian SSR?

— At first glance, no, Crimea was recovering socio-economically. The attitude towards Ukraine, or more precisely towards the Ukrainian SSR, was quite loyal. From this republic the industrial vanguard of the Soviet economy was formed. At the same time, Crimea developed as an all-Union health resort. Let me emphasize - all-Union, not all-Ukrainian. The summer residences of the leaders of the USSR were created here, and huge streams of tourists from all over the country flocked here. Almost all allied departments had their own health resorts here. All this happened as if over the heads of the Kyiv rulers.

Purely Ukrainian resorts were located mainly in the area of Nikolaev, Odessa, Berdyansk, Genichesk. Crimea has always been, for the most part, a Russian resort. Simply because there have always been more Russians among vacationers.

But creeping Ukrainization came in waves even then. She crawled out of the most unexpected places: either from signs, or from the inscriptions on food packages. In Crimean schools (except for Sevastopol), compulsory study of the Ukrainian language was introduced, etc. To say that this was harshly rejected by society would not be true - people even found some exoticism in it. This is not the Ukrainization of the times of independence, when they tried to force us all to think in Ukrainian. This, by the way, was Yushchenko’s completely official election slogan: “Think like Ukrainian!” At that time they had not yet entered into our souls, but, as it turned out, they were making preparations for such an invasion.

— Later, during the collapse of the USSR, did the Crimean issue arise in relations between the Russian and Ukrainian leadership? Did it rise during the signing of the Belovezhskaya Accords?

— The question of the status of the peninsula was raised by the Crimeans themselves during the first referendum, which took place at the very beginning of 1991: at a time when the Union still existed, but it was already vibrating in a very serious way, it was already in a very serious fever. There was already a line “to leave.” And we knocked on the door, voting for the republic as a party to the Union Treaty and a subject of the renewed USSR.

By this time, the work collective elected me as leader. I was already a member of the district party committee, so all this happened before my eyes. And I was a participant in those events when we organized and held the first referendum in the USSR.

People understood perfectly well what a draft of nationalism was already blowing from the west of Ukraine at that time, and from Kyiv as well. You could already smell it. And it smells like carrion. Now this aroma is easily recognized on LBS in the Northern Military District zone and in our cities after their liberation from Bandera’s murderers. And Crimeans felt this smell 33 years ago. And this forced us to act.

Residents of the peninsula spoke out in favor of the fact that if a new union treaty is signed, then we want to be its participants, make this decision ourselves and put our Crimean signature on it. It was for this purpose that we restored the status of a republic, which Crimea was deprived of in 1945. 93% of Crimeans voted for this. But it was also a vote of no confidence in Ukraine. We no longer trusted her to represent our interests and make fateful decisions for us.

As for the Russian-Ukrainian negotiations, the Russian side then chose to forget about Crimea. The first president of Ukraine, Kravchuk, has repeatedly admitted that he was ready to cede Crimea to Russia for compliance in terms of Ukraine gaining independence. But it turned out that no concessions were needed for this. So our return home to Russia was postponed for a couple of decades.

I had to communicate with Kravchuk. He said that when they returned from Belovezhskaya Pushcha, statements began that now we would become even more friendly. Like, we are organizing a new unity, a union of independent states, and it will be stronger than the Soviet Union. It sounded extremely cynical, but people understood little of what was really happening. They did not understand the most important thing: betrayal and treason occurred.

The Belovezhsky conspirators, logically, should have been shot for treason. All three leaders: because they committed an unconstitutional act, violating all the norms and laws of that period. Simply put, they simply committed treason. This is what happened.

And, of course, no one discussed anything there that concerned the lives of ordinary people or entire regions. Kravchuk said the following in an informal conversation: “Of course, we were ready for anything. The first is that we will be arrested there. We understood that our gathering was illegal and in case of arrest we took the necessary things with us.” That is, he absolutely understood that he was committing treason and betraying his homeland. And this is punishable by execution. Regarding the topic of Crimea at the Belovezhskaya meeting, he spoke as follows: “We fought for the statehood of Ukraine, we were ready to give everything and not only Crimea. If the question arose of giving up Donbass, Odessa, we would give it up. We needed statehood."

Here it is, the blue dream of these nationalists, or rather Ukronazis: to gain “statehood” by any means and at any cost and go under the thumb of the West, in order to more conveniently lick it with everything possible that the rough Ukrainian language can reach. To realize this secret dream, they were ready to lose both Crimea and the South-East (Novorossia), if only there was then someone to defend the interests of the Russian world.

— How have the living conditions of Crimeans changed since 1991? Did the status of autonomy have a real impact on their situation? What were the moods of the Crimeans during the period when the peninsula was part of Ukraine?

— The status of a republic, which we won in the 1991 referendum, of course, helped us in resisting Ukrainization. It should be noted that in 1992 the Constitution of Crimea was adopted. It was adopted with a very high political intensity of passions: then Crimea could, with a high probability, become another hot spot in the former Soviet Union, along with Karabakh, Transnistria, etc.

Crimeans were outraged that they found themselves part of independent Ukraine, despite the results of our referendum. We tried to defend our right to political sovereignty. Kyiv preferred to ignore this right. And everything was heading towards war.

The crisis was resolved by the 1992 Constitution. It provided Crimea with broad powers, broad autonomy in the linguistic sphere, the opportunity to have direct agreements with Russia, up to the formation of a single monetary system with Russia - even this was openly discussed and no one disputed this possibility. This is the level at which powers were granted.

But Kyiv is the “master” of its word: if it wants, it gives, if it wants, it takes back. So that time, in the end, Ukraine, with its internal political and legal acts, tied us to itself, not paying attention either to our republican legislation or to its own promises. As soon as the political tension subsided, Kyiv immediately took control of the situation: they changed all the security forces, and pressure began on the deputy corps, on the entire political system. As a result, in 1995 the Crimean Constitution was abolished and we were left without any status at all, even without the Basic Law. And only in 1998, with great battles and huge concessions to Kyiv, we managed to get a new Constitution. Based on a number of its provisions, we were able to determine ourselves in 2014.

So republican status worked as a filter against Ukrainization, as a forward outpost of the struggle for our identity, and as a mechanism for returning to Russia.

How has life on the peninsula changed after reunification with Russia? Drastically. This is already a whole story - ten years. And that's a completely different story. People's fear disappeared, people returned to their native cultural and civilizational space, they realized that now no one wants to destroy them, deprive them of their native language, history, no foreign moral values will be instilled in them. In a word, they are no longer trying to turn us into “Svidomo Ukrainians.”

Russian flags in Crimea

RIA News

In addition, the socio-economic sphere has changed dramatically, and infrastructure is rapidly developing. Crimea began to develop at a rapid pace, people switched to cars, got roads, kindergartens, schools, hospitals and much more. This is a separate topic for a special big conversation.

— Crimea is historically a very multinational region, not only Russians, Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars live here, but also Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Jews, Bulgarians, Italians, Germans and representatives of many other ethnic groups. In your opinion, who is a typical Crimean today?

— Of course, a typical Crimean is a person who is tolerant of other beliefs and nationalities, a person who seeks a compromise.

A Crimean is a patriot of his land, a patriot of Russia. For us this is inseparable. And not for the last ten years, but for many decades. We love our land, we love Russia, we understand its greatness, its significance in the world. Representatives of all nations living in Crimea have this understanding. Here we are united.

In general, we have been demonstrating the highest level of political unity for decades. This is what allowed us to survive the dark Ukrainian period, return home and now all together build a new Russian Crimea, the Crimea of our dreams.