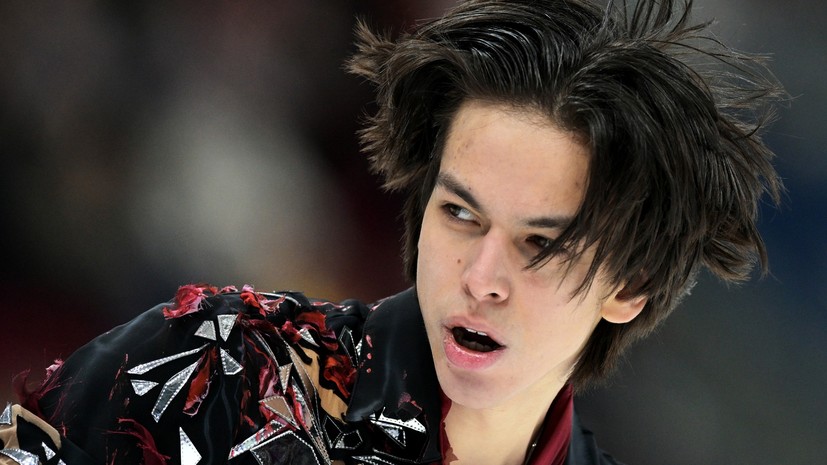

The pre-planned interview almost fell through. We agreed with the coach to meet in Moscow at the Russian jumping championship and, naturally, it could not have occurred to anyone that, having successfully qualified, in the final of the personal tournament Gumennik would skate so unsuccessfully that the coach would say: “I don’t even know what I can do.” tell me after this..."

And yet the conversation took place.

— It is clear that any sports defeat is not the most favorable time for an interview, but it is a good reason to ask: is an athlete like Gumennik a gift of fate, or a coaching cross?

— I would say that for great coaches this may not be a gift at all. Peter is complex and ambiguous. Incredibly talented, with an amazing sense of rhythm, a sense of his own body, but he really likes to do things his own way. And this is a quality for an athlete that cannot be said to always be a plus. But since I am a mid-level coach, it was very interesting for me from the very beginning of our work together. If Petya had not grown so much, he would have been even better, it seems to me.

- Are you saying that you didn’t expect this?

— I assumed. Gumennik’s mom and dad are short, and they were sure that their son would not actively grow as he grew older. I took into account not so much heredity as a combination of certain characteristics. You know how it happens: you look at a thoroughbred and still awkward foal with disproportionately large joints and immediately understand that he will grow into a large and powerful horse. She even told her parents then: I wouldn’t be surprised if Petya grows to 175 cm. And she turned out to be right.

- But it looks so beautiful when such tall guys as Gumennik or Makar Ignatov jump well. Miniature athletes will never achieve such an impression on the ice.

- This is a double-edged sword. It is difficult for tall skaters to “calibrate”. They are not so nimble, it is not easy for them to control their size. One inaccuracy and everything went wrong. A small athlete can fall out of the axis in a jump and still stay on the landing. Imagine if a tall and powerful guy is not part of the axis? He will destroy the entire skating rink. No amount of vestibular disease will help, although Peter’s is very, very good.

— For me, in fact, it’s a big mystery: how, with so many difficult jumps, your student copes with such a dramatically complex free program as “Dorian Gray.” He doesn’t just ride, he lives in it.

— This program very much coincided with Petya’s internal state, which is sometimes very contradictory. On the one hand, he is from an Orthodox family, where Orthodox principles are at the forefront: decency, kindness, observance of certain commandments. Accordingly, it is ingrained in the mind: don’t do bad things to others, they’ll come. Moreover, all three sons in the family are not only very well brought up, but developed in all directions. Music, mathematics, sports, and the music is very diverse, without any restrictions. The only time was when we thought of taking a melody from the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar for one of Petit’s programs, but my parents immediately made it clear that they did not approve of this idea. That there is a line that should not be crossed.

— But “Dorian Gray” is also a rather ambiguous choice in this regard.

“Partly, the same upbringing and wide range of interests worked great here. Well, what kind of “Dorian” could we have made if Petya hadn’t read all this, didn’t play it, didn’t let it pass through himself? After all, he so reliably conveys the image of a hero who, in his inner essence, is an absolute scoundrel, that sometimes even I want to crack him with something - to such an extent I cease to understand: whether this is an absolute adaptation to the role, or some other, dark one. side of nature. Sometimes I even laugh: if not for such a deep and correct upbringing, Petya could have become an absolutely outstanding criminal - is it not by chance that Daniil Gleikhengauz saw this image in him? It seems to me that with his intelligence, he would be able to effortlessly calculate any criminal combination.

— When was it easier to work with Gumennik, in childhood or now?

- He has always been difficult and independent. It’s easier now because I’ve grown up and started talking. Before that, I was somehow more on my own. Because of this, one day I couldn’t even stand it, I told my mother: “I can’t do it anymore, I don’t have the strength to work with him.” She told me: “Veronica Anatolyevna, calm down, everything will pass, I promise.”

— So, it was just a stage of adolescence?

- Well, yes. I guess I just expected too much from him. I saw that the guy was not just talented, but multifaceted. He has many interests, but they are all developmental, or something.

— What do you think helps your athlete on the ice more, mathematics or music?

— Sometimes it seems to me that music does not allow Petya to go crazy with mathematics. And vice versa. He is a fan of learning. He understands that he is now mortgaging his own future and is trying to learn everything thoroughly. He trusts the exact numbers very much. And sports are perceived in exactly the same way. He constantly has to explain everything through the prism of biomechanics. There is a whole website where he breaks down all his jumps. Exit angles, arc radii...

— In your coaching career, Gumennik is the first athlete of this level, next to whom you yourself grow as a specialist. Are you afraid of doing something wrong?

- Petya came to me as a teenager, when there was no talk of any outstanding level. At first I pulled him up based on my knowledge. And then she once said: when will you start dragging me along with you? Now I can completely rely on him in some matters.

— After a not very successful start at the Russian Grand Prix in Krasnoyarsk, you said quite categorically: no more interviews, only training and study. Does communicating with journalists unsettle your ward so much?

- The point is different. At that time, Petya was a little scattered, and this really got in the way. After all, he studies at a very serious institute - precision mechanics and optics (ITMO - RT). If my own child were in Gumennik’s place, I don’t even know what I would advise him to choose: a career as a figure skater, or study. I understand perfectly well that studying at this institute can give a person a profession that will provide for a family much more reliably in the future than figure skating. Even if after the end of his career Petya continues to skate in the show.

— From the outside, he doesn’t seem like a person whose ultimate dream is to make money on the show.

- In fact of the matter. He told me many times that he doesn’t want to be a coach, doesn’t want to be on the show, but wants a good profession. Now, perhaps, he himself understands that it will be easier to earn money while remaining on the ice. This, whatever one may say, is a profession that he has been engaged in since the age of five and knows everything about it. And in the same computer science, he has to break through and break through.

Veronica Daineko

RIA News

© Alexander Wilf

— Did you immediately want to become a coach?

- Straightaway. I even wrote an essay on this topic. It seemed to me that coaching was much easier than being an athlete. If I knew what it really was like, I probably wouldn’t want to.

— Is it really possible to be so disappointed in the profession?

- This is not disappointment, no. But I really mentally dismiss myself after every unsuccessful start, despite the fact that I understand perfectly well: I just have to endure it. Perhaps I'm just tired of waiting for results. After all, I want everything to work out two, three, four times faster.

— Alas, this happens extremely rarely in the coaching profession.

“So my husband tells me: if you sit on the stove with your bare butt, it won’t make it work more efficiently.” But I suffer every time my children make mistakes in competitions. I understand that for consistently high results, you need to build an entire system, with the selection of certain specialists.

—You don’t have such an opportunity?

— Tamara Nikolaevna (Moskvina - RT ) gave me this opportunity. I could not get.

- Why? Has the habit of taking everything on yourself worked?

- Probably not. It is important for me to feel that I can completely trust a person and rely on him in everything. And I am constantly looking for when such a person will appear. But I'm afraid of betrayal. I can't stand it well. When I talk to coaches who have teams, I hear from them: “Veronica, it’s normal when a team doesn’t come together right away. Even if you lose something, you will definitely find something else.” I guess I'm just coming to this understanding. Now, for example, Nikolai Moroshkin and Alexandra Panfilova help me a lot in my work. And I myself feel like I’m part of Moskvina’s big team and I’m constantly learning, and not only from her: I grabbed it here, I grabbed it there, I spied something from one master, from another. Sometimes contradictory things arise, and you start doing research. What I call it is up to the detectives to decide. Build a system of your own understanding of the process.

- Who is easier to work with - boys or girls?

— I always thought that with girls it’s more difficult in terms of puberty. That's why I wanted to train boys. It turned out that this was no better. When adolescence sets in, arms and legs begin to grow completely differently, and this causes coordination problems. Plus, you are constantly waiting for the boy to finally become a man and for a positive increase in speed and strength to begin. But it doesn’t exist, because puberty is somehow inhibited by training, and this happens in its own way for each athlete. As Alexey Nikolaevich Mishin says, we have to wait for the boys.

— Why, by the way, after several years of working together, did you decide to leave Mishin and go on your own?

— Because another skating rink opened, we were sent there with Oleg Tataurov, and we trained the children together. Well, then, together with Gumennik, I ended up at Tamara Nikolaevna’s school.

— Moskvina always seemed to me a more stern boss.

- Everything is very relative here. Everyone expects different things from their bosses. For some it is important that their work is not interfered with, for others it is the opposite. It’s just that Mishin was never my boss in the usual sense of the word. I think he just wasn’t interested in me, let’s put it that way. There were enough other worries. Moskvina, like a true woman, very painstakingly creates a nest around herself, raises “chicks”, and makes sure that they are all under supervision. He can praise, he can scold, he can help resolve some issues not related to training and competitions.

— Recalling the beginning of her own coaching career, Tamara Nikolaevna once admitted to me: “When I started working, for many years I saw only backs in front of me. The back of Elena Tchaikovskaya, Tatyana Tarasova, Stanislav Zhuk, her own husband..."

- Well said.

- Familiar feeling?

- Yes. I remember when some athletes left me for other coaches, at first I felt sorry for myself to the point of a nervous breakdown. And it’s very disappointing. It seemed so unfair to me that I constantly seemed to be expecting retribution. Only then did I begin to understand: each such departure means that you yourself could not stand the competition. Didn’t plan, didn’t finish, didn’t puff.

- But athletes often leave just for administrative resources, for more favorable conditions.

“They always go where it’s better.” Where they give more knowledge, more stability, more of the same resource, finally. If someone was able to provide all this, but you couldn’t, it means you didn’t do your job very well.

— At the moment, under your leadership, Gumennik has achieved almost prohibitive technical complexity. In what direction can he develop himself most strongly in comparison with his current state?

— Difficulty should become stable. To do this you need to work a lot on your jumping technique. Not double, not triple, but quadruple. Just like figure skaters on a jump rope jump with double or even triple twists, without thinking at all about how they do it, elements on ice should be brought to the same automatic skill.

— Still, quadruple jumps put a lot of stress on your head. To jump consistently, you need to jump a lot, but I’m not sure that in this case you can achieve stability with just the number of repetitions.

- Of course not. This requires not only good knowledge of technology and biomechanics, but also a certain physical condition in order to load the body without the risk of injury. If the body condition is insufficient, this cannot be compensated for by anything. Plus - sliding. This is the basis of all elements.

— What is it like to teach an athlete how to jump quadruples when you have never jumped them yourself?

- Scary, of course. When I started working, it seemed to me that triples would be enough for my coaching life. I know 350 thousand ways to do a triple jump. I won many children's championships with my little one. But for an athlete to do the first quad, I had to learn a lot again.

— With regard to multi-rotation jumps in figure skating, discussions are constantly underway: whether one should strive to increase the height of the jump, or whether it is enough to develop a high initial rotation speed.

- These are just two different approaches. Let’s say Mishin’s jumping technique, which is used by many coaches around the world and which works great, has always been based precisely on group density and rotation speed. And Igor Borisovich Ksenofontov based his training on pushing out the ice, on free passages that give the jump height and amplitude. It is believed that this approach is more tailored to the athlete’s weight. As the weight gets heavier, the pressure on the ice also increases. If you hit the takeoff well, you fly even further.

Here, a lot depends on what kind of school you went through when you were an athlete. For example, Ilya Malinin’s parents once skated with Ksenofontov, and it is logical to assume that they teach their own son some things in the same way. But here, as they say, you choose the stairway to heaven yourself.

“I understand the sporting goal that drives Gumennik. What motivates you?

— If we talk about figure skating in general, I would like even my youngest students to become figure skaters. So that, figuratively speaking, they don’t have sneakers on their feet, but skates. So that this horse would carry them, push them out, rotate them, circle them. Or at least it didn’t interfere, as it sometimes interferes with many even adult athletes. I talk to Petya about this all the time.

But in terms of a serious result, I really want to wait for the moment when everything comes together.

— To see your athlete become completely unattainable?

— Rather, to feel that I myself have succeeded as a coach.