Russian scientists from NUST MISiS together with colleagues from Moscow State University.

MV Lomonosov and the State Historical Museum found out exactly how the famous medieval swords Ulfberht (Ulfbert) were forged.

This was reported to RT by the press service of NUST MISIS.

Ulfberht-marked swords were very popular in Europe, and the history of their production stretched from the end of the 8th century to the 11th century.

The best examples of such blades were distinguished by a combination of strength, lightness and flexibility.

Thanks to special structural studies, primarily metallographic, scientists were able to establish what technology was used by medieval gunsmiths.

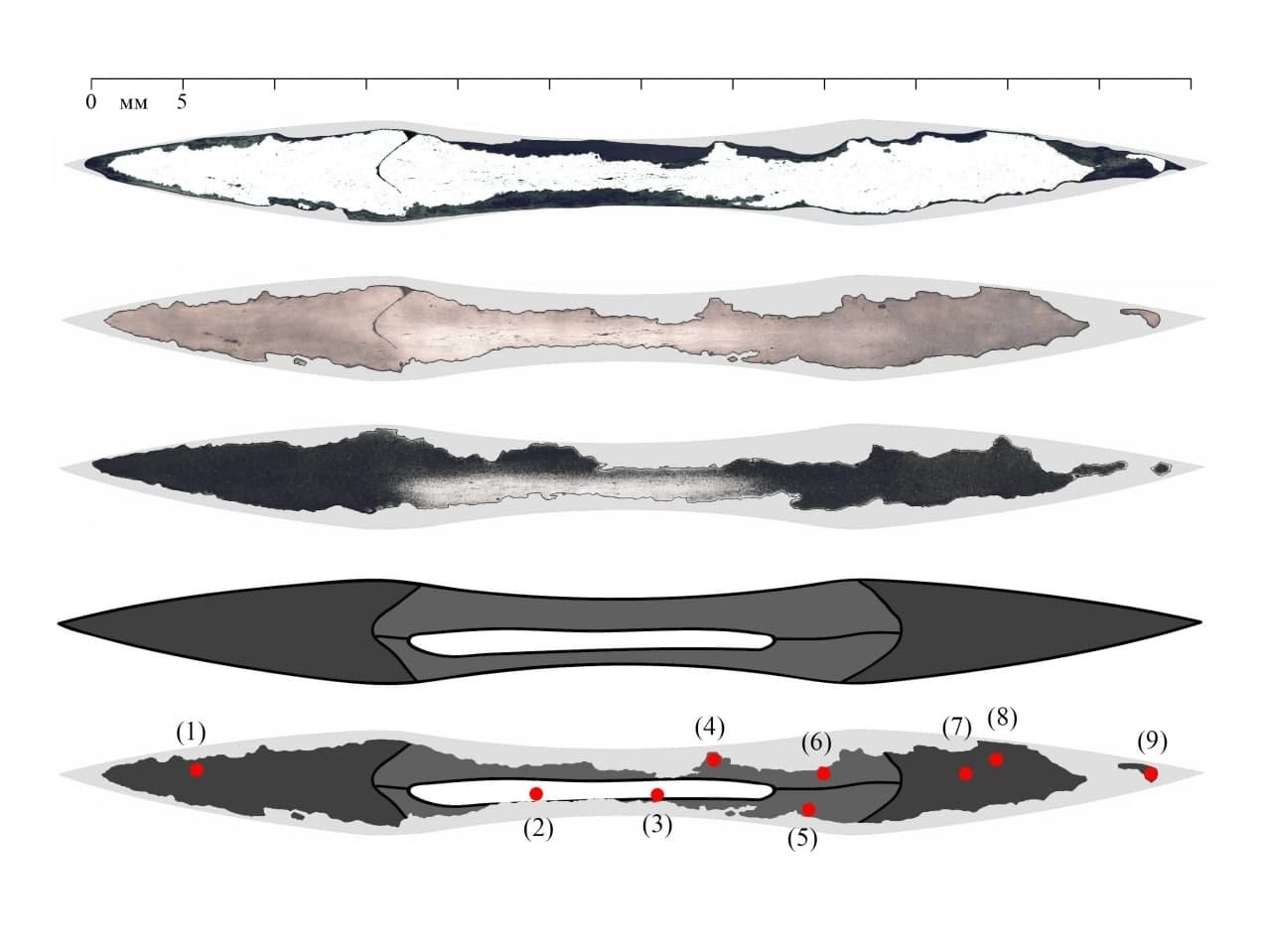

The structure of the blade of the Ulfberht sword from Gnezdovo: a three-layer core with welded edges of steel

© NUST MISIS Press Service

As the head of the laboratory "Hybrid Nanostructured Materials" of NUST "MISiS", Ph.D., said in an interview with RT.

Alexander Komissarov, swords with the mark Ulfberht could be forged from steel of very different quality.

“Quality blades contain high carbon steel.

There is a widespread legend that Ulfbert's swords are made of cast crucible steel, comparable in quality to modern metal.

Our research refutes this myth: welds, structure heterogeneities and slag inclusions were found in all swords, ”the scientist noted.

The level of medieval technology did not allow the production of high-quality steels.

Nowadays, metal is melted at temperatures above 1650 degrees Celsius.

This melting temperature allows not only to separate the slag, but also to enrich the iron with a large amount of carbon.

Medieval blacksmiths were not yet able to heat metal to such high temperatures.

As Alexandra Shchedrina, a graduate student of the Department of Archeology of Lomonosov Moscow State University, a graduate of the Department of Metal Science and Strength Physics of NUST MISiS, explained, in medieval Europe, iron was obtained by the so-called blooming method.

It made it possible to obtain a loose lump of softened sponge iron mixed with slag and particles of unburned coal, which is formed during the smelting of iron ore at relatively low temperatures.

The Russian name of the method comes from the Old Russian "kr'ch" - a blacksmith.

Kritsu is also called raw iron.

The slag was removed from the metal by repeated forging, and carbon could only get into the iron by carburizing - heating the already finished metal in the presence of carbon additives, such as coal.

© NUST MISIS Press Service

“The materials available for the manufacture of weapons were heterogeneous and far from ideal in quality, and metallurgists learned to alloy steel much later.

In order to get high-quality, solid and reliable blades, like Ulfberht swords, blacksmiths tried to combine different materials in one product: hard hardened steel was used on the edges, and the blade core was made of iron, which has the highest impact strength, ”said Alexandra Shchedrina in an interview with RT .

Metal experts have studied several blades of the 10th century from the Gnezdovo archaeological complex near Smolensk and the mounds of the South-Eastern Ladoga region.

The swords are marked with the hallmark +VLFBERHT+, transcribed by modern historians as Ulfberht ("Ulfberht").

Archaeologists find such a brand on swords made in the early Middle Ages in Europe.

Historians have not yet been able to accurately establish the place where this weapon was forged, presumably we can talk about the Rhineland, which was located on the territory of modern Germany.

Most likely, it was not about one forge, but about a whole group of hereditary workshops.

Such swords were found by archaeologists in a number of European countries, but most of the finds were made in the Scandinavian countries.

A lot of blades with such a stigma were found on the territory of Russia, Ukraine and the Baltic states.

Scientists explain this pattern by the peculiarities of the burial traditions of the peoples of that era.

In Scandinavia and neighboring regions, the pagan custom of placing a sword in a warrior's grave was preserved longer than in Western Europe, while in Western European countries weapons were inherited.

The name "Viking swords" today is firmly entrenched in blades bearing the Ulfberht mark.