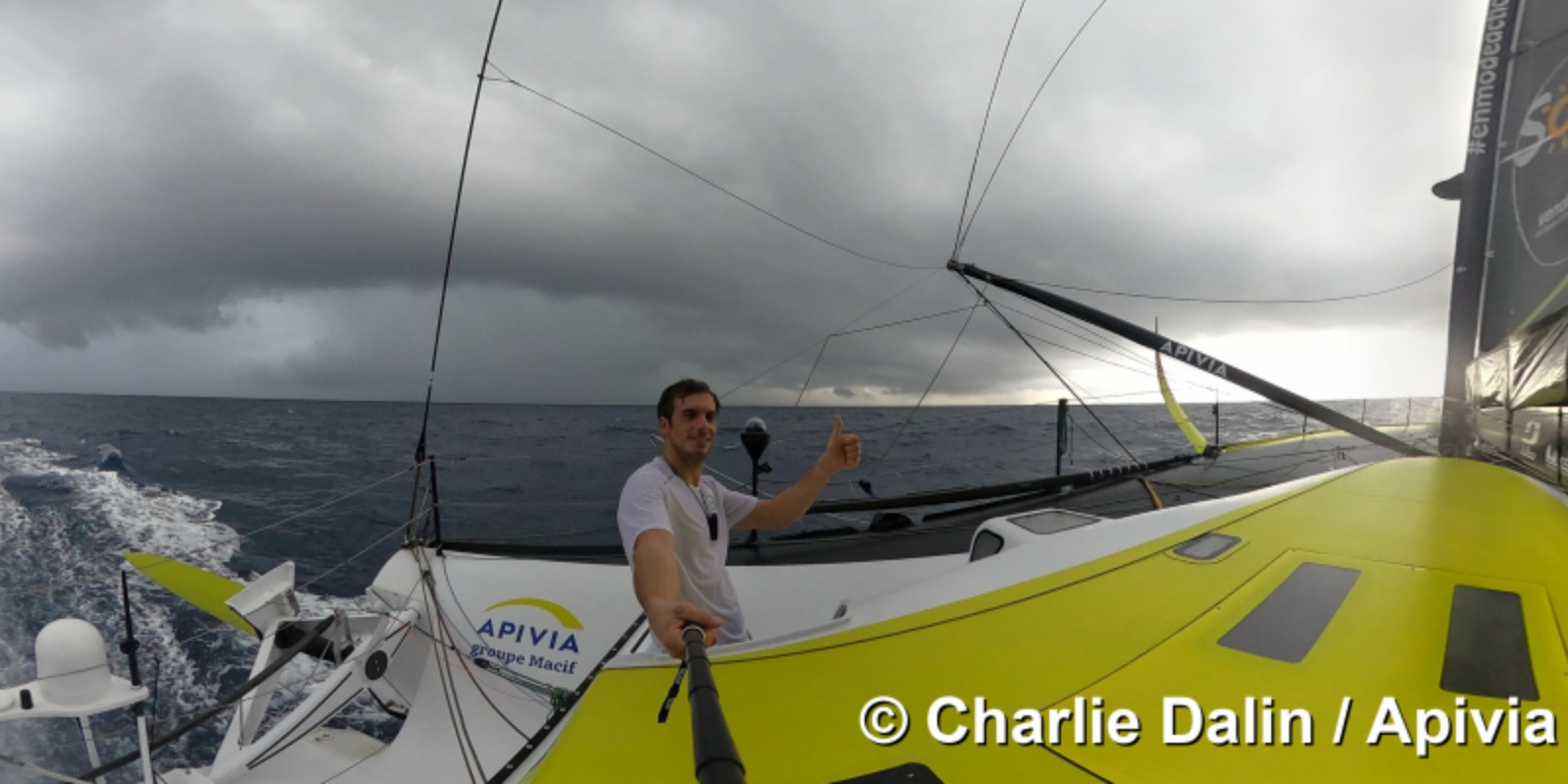

Every Saturday during the Vendée Globe, Charlie Dalin keeps a logbook for Europe 1. On his Apivia monohull, the 36-year-old skipper talks about his impressions, his strategy and the future events that await him in this legendary single-handed race. , nonstop and unassisted.

In this tenth week of the Vendée Globe, Charlie Dalin has taken the lead again. The 36-year-old skipper, who is taking part in his first edition on his Apivia monohull, is sailing "a few dozen kilometers from the Brazilian coast" and heading for Ecuador and the Doldrums. The navigator confides in his weekly logbook on Europe 1, recorded on Friday.

Back in the lead

"I lost the head of the race a month ago exactly, on December 15, following my foil hold problem, I found it a few days ago and it feels good. As what everything is possible , you should never give up.

I am in an incredible South Atlantic Ocean with a semi-permanent cold front near Cabo Frio [

a Brazilian city in the state of Rio de Janeiro, note

].

This meteorological barrier allowed part of the fleet, including myself, to catch up with Yannick Bestaven, when he was 900 kilometers ahead.

It seemed almost unexpected, but the weather allowed me to do it and it's great.

There is still a long way to go, but it feels good to be back in the lead.

Having boats side by side pushes us to be even more precise on the adjustments, regular on the adjustments.

We must not forget that this is not a one day race, we still have two weeks and we have to keep up.

Vendée Globe: find all of Charlie Dalin's logbooks

There is still almost a Transat Jacques Vabre to do [

a duo transatlantic race between France and South America, note

], there will still be a lot going on and we are tired, the boats are tired.

You also have to factor that into the equation.

No one is "100%" anymore

However, everything changes between the position of leader of the race and the place of second: when you are a hunter, you are on the lookout for opportunities, openings.

But when you are the hunted, you try to anticipate the openings that the competitors might have and to position themselves accordingly [

the first six competitors are in a pocket handkerchief, note

].

It's true that there are a lot of boats, but I'm used to it, I was trained in regatta so for me it's more natural to sail like that than in his corner.

Regarding the potential of the other boats, whether it is one because a repair is weak or because of a torn or even lost sail, for me it is clear that no one is 100% any more.

Afterwards, it's true that the public is always a little upset that we don't share all of our problems, but it's a bit like someone revealing the strengths of their card game.

This is strategic information and it is normal to hide what can be, I myself am on the lookout for information on the potential problems of my opponents.

It helps me to know their conditions, it is strategic information for the race.

The unknown of the Doldrums

I can't wait to cross Ecuador again, finding my hemisphere is a great step towards the end of the race, towards home.

When I crossed it on the way out, I was really heading for those southern seas that I did not know at all, the unknown.

I knew a lot of things were going to happen to me but I didn't know what.

There were storms, bilges, galleys, but moments of joy too.

This passage from Ecuador on the first leg was really a leap into the unknown, but I knew that if everything went well I would manage to cross it again in the other direction several weeks later, and that I would be different.

Now, I am happy to find my good old northern hemisphere and Les Sables d'Olonne.

But before returning to the French coast, you have to cross the Doldrums.

If on the way out we were spared enough, I had some difficult times in this area.

Especially in 2019 when I brought my boat back alone during the Transat Jacques Vabre.

However, we are supposed to be in a season where he is less strong, in any case that is what is written in the books ... But in reality we know when we enter but we never know when we leave it, nor in what sauce we are going to be eaten.

We must therefore wait to clear this obstacle before starting to calculate the estimated time of arrival (ETA).