When the underwater internet cables gather in one place, things become difficult, and perhaps that is why Egypt is considered the most dangerous region for submarine cables, as it has a large number of cables that pass through most of the internet traffic around the world.

Serious cable break

The Asia-Africa-Europe-1 internet cable travels 15,500 miles (about 25,000 kilometers) along the sea floor, connecting Hong Kong to Marseille in France.

As it passes through the South China Sea towards Europe, the cable helps provide internet connections to more than a dozen countries, from India to Greece.

When the cable also known as "AAE-1" (AAE-1) that briefly runs over the earth through Egypt was cut on June 7, millions of people were cut off from the Internet and faced a temporary blackout for an unknown reason.

“It affected about 7 countries and a number of super-services," says Rosalind Thomas, managing director of SAEx International Management, which plans to build a new subsea cable connecting Africa, Asia and the United States.

Thomas added: "The worst was Ethiopia, which lost 90% of its connection with Somalia, and after that Somalia also lost 85%."

Google, Amazon and Microsoft cloud services have also been disabled.

While connectivity was restored within a few hours, the outage highlights the fragility of the world's 550+ undersea internet cables, as well as the huge role of Egypt and the Red Sea in the internet infrastructure.

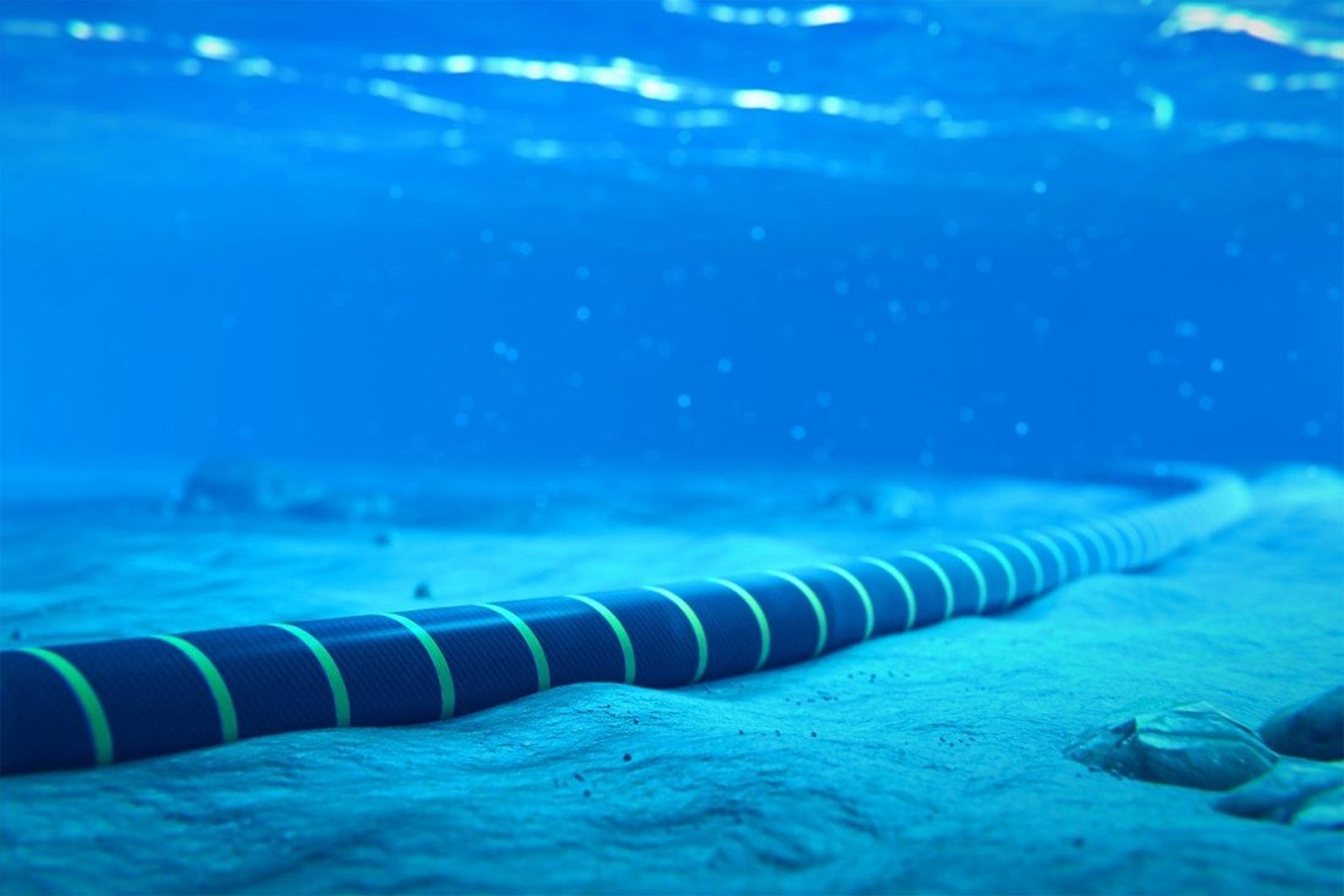

The global network of underwater cables makes up a large part of the backbone of the Internet, carrying the majority of data around the world (Getty Images)

The fragility of underwater cables

The global network of underwater cables makes up a large part of the backbone of the Internet, carrying the majority of data around the world and ultimately connecting to the networks that power cellular towers and Wi-Fi connections.

Undersea cables link New York, London and Australia to Los Angeles.

16 of these submarine cables, which are often no thicker than a hosepipe and are susceptible to damage from either ship anchors or earthquakes, pass 1,200 miles (about 1,930 km) across the Red Sea before hopping over land in Egypt and reaching the Mediterranean. It connects Europe with Asia.

The past two decades have seen the path emerge as one of the world's largest internet cable congestion points, and arguably the internet's most vulnerable spot on Earth.

(The area, which also includes the Suez Canal, is also a global choke point for shipping and the movement of goods.)

“Where there are congestion points, there are single points of failure,” said Nicole Staruselsky, associate professor of media, culture and communication at New York University and author of a book on submarine cables. the scientist".

The area has also recently gained attention from the European Parliament, which highlighted it in a June report that said it poses a widespread risk of internet disruption.

“The most important obstacle for the EU is related to the passage between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean through the Red Sea, because the primary connection to Asia passes through this route,” the report says, citing extremism and maritime terrorism as risks in the region.

The US has average home internet speeds of 167 Mbps (Shutterstock)

pyramid diagram

When you look at Egypt on a map of the world's undersea internet cables, it becomes immediately clear why internet experts have been worried about the region for years.

The 16 cables are centered in the region across the Red Sea and touch the ground in Egypt, making a 100-mile journey across the country to reach the Mediterranean.

It is estimated that about 17% of the internet traffic in the world travels with these cables and passes through Egypt.

Last year the region had a capacity of 178 terabytes, or 178 million Mbps, says Alan Mauldin, director of research at telecom market research firm TeleGeography, and the US has average home internet speeds of 167 Mbps. .

Doug Madhuri, director of internet analysis at Kinetic Monitoring Company, says that Egypt has become one of the most prominent Internet traffic throttling points for several reasons.

The most important of these reasons is its geography, which contributes to the concentration of cables in the region. The passage through the Red Sea and through Egypt is the shortest underwater route between Asia and Europe.

While some transcontinental internet cables travel over land, it is generally safe to lay them on the sea floor where they are difficult to disrupt.

And going through Egypt is one of the only practical ways to go south. The cables around Africa are longer;

In the north, only one cable, the Polar Express, travels over Russia.

“Every time someone tries to plot an alternate route, they end up going through Syria, Iraq, Iran or Afghanistan, and all of these places have a lot of problems,” Madhuri says.

Madhuri adds that the JADI cable system that bypassed Egypt was shut down due to the civil war in Syria, and has not been reactivated.

In March of this year, another cable that does not pass through Egypt was cut as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Mauldin says that Egypt can be considered one point of failure, but it is significant because of the number of cables in one place.

However, there are reasons other than costs that prevent many cables from passing through the Red Sea.

When submarine cables appear above land, in the far north of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez, they fall under the control of Telecom Egypt, the country's main internet provider.

The company charges cable owners for running cables across the country.

The cables travel across the land between several different routes - and do not pass through the Suez Canal - so there is a difference in how they are spread.

In the opinion of Staroselsky, "this gives Egypt a great deal of power in terms of communications negotiations."

A recent report by Data Center Dynamics, which covers the "chokehold" on the submarine cable industry, cites unnamed industry sources claiming that Telecom Egypt charges "exorbitant" fees for its services.

Google announced that it is constructing a Blue-Raman submarine cable that will connect India with France (Anadolu Agency)

wire tie tape

Marine cables are relatively fragile and easily damaged. Every year, there are more than 100 accidents in which cables are cut or damaged, and most of these causes are caused by shipping or environmental damage.

However, in recent months, there have been growing concerns about sabotage. In the wake of the Nord Stream gas pipeline explosions, governments around the world have pledged to better protect underwater infrastructure and submarine cables.

The UK also claimed that Russian submarines monitor cables in the country.

Despite the risks, the Internet is built on resilience.

It is not easy to remove large parts of the Internet.

And companies that send data over undersea internet cables don't just use one cable and will have space on multiple cables.

If one cable fails, traffic is eventually redirected over other cables. In some areas, such as Tonga, where there is only one cable, interruptions can have devastating effects, and the need for redundancy is why Google, Facebook and Microsoft spend hundreds of millions on their internet cables under the sea in recent years.

When it comes to Egypt and the Red Sea, options are limited, and cables are often the answer.

While Elon Musk's Starlink has deployed satellite Internet, this type of system does not provide an alternative to underwater cables.

Satellites are used to provide communication in rural locations or as emergency backups, but they cannot replace the entire physical infrastructure.

And they will not deal with the transfer of hundreds of terabits between continents.

Mauldin says that satellite systems also rely on wired connections to connect to the Internet.

This is all the more reason for more protection for the roads around Egypt.

Mauldin explains that additional landing sites are being built along the Egyptian coast, such as Ras Ghareb, to allow cables to anchor at different locations.

The Egyptian telecom authorities are also building a new overland cable route along the Suez Canal, and it is believed that the cables will be laid in concrete channels to protect them.

However, the biggest effort to bypass Egypt comes from Google.

In July 2021, the company announced that it was constructing a Blue-Raman submarine cable that would connect India with France.

The cable travels through the Red Sea, but instead of crossing land in Egypt, it reaches the Mediterranean via Israel.

Mauldin says the new route, which is expected to be ready in 2024, is likely to set a precedent that opens the way for more cables to travel through Israel over time.

Once you build one cable, the others will come.

"It's hard to turn a proposal or just a good idea into reality, unless you're Google and you have unlimited money to do these things," Madhuri adds.

Elsewhere, Thomas says, the proposed CX cable plans to bypass Europe and connect Africa to the Americas and Singapore.

In the end, Egypt will always be at the center of Internet connections in Europe and Asia, as geography cannot be changed.

However, Mauldin says, more needs to be done to protect the underwater internet cables in the world, where everyone depends on them.