Even before the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian war

Economic relations between the European Union and China are steadily deteriorating

China-EU relations are at stake after economic sanctions.

Getty

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has caused a rift between the European Union and China, for the first time in the history of their relationship, and Brussels appears to be poised to go further. The world's second and third largest economies have been at odds since March 2021, when the European Parliament suspended ratification of the comprehensive agreement. to invest due to human rights concerns.

But since the entry of Russian forces into Ukraine on February 24, relations have deteriorated further, and there appears to be little prospect of any reconciliation.

Brussels appears angry at Beijing's refusal to condemn Russia's aggression against Ukraine.

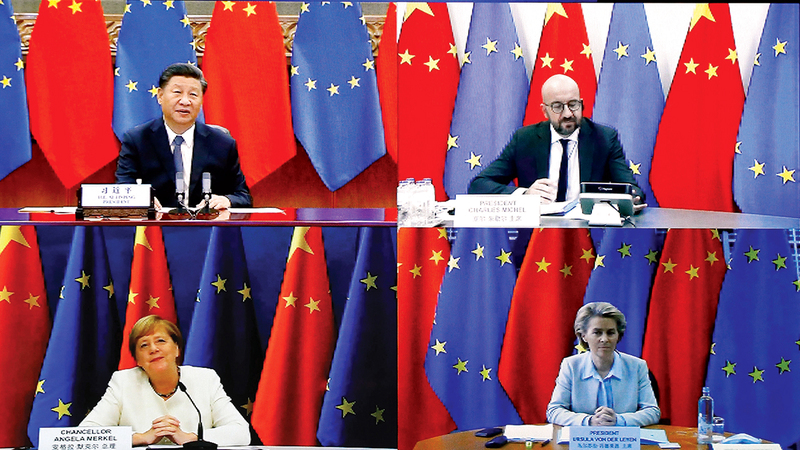

In the early days of the war, EU officials had hoped that China would try to broker a peace deal, but a frosty virtual summit between EU leaders and Chinese President Xi Jinping, on April 1, dashed those expectations.

More importantly, as the war in Ukraine has forced Europe to start thinking geopolitically for the first time since 1991, EU countries' growth forecasts for 2022 have fallen amid rising energy prices.

It also appears that the EU's long-standing assumption that economics can substitute for actual foreign policy in dealing with abusive states is now a bad bet.

In the past few weeks, the European Commission has presented an ambitious set of policies to keep Europe economically distancing itself from China.

Some of these policies predate the war. In December 2021 the Commission introduced an anti-economic coercion mechanism that would enable Brussels to impose trade retaliatory measures on imports from countries that apply economic coercion to EU member states.

These measures clearly target Beijing, which in 2021 placed Lithuania under a de facto trade embargo, after Lithuania allowed Taiwan to open a representative office in the country.

But most of the European Commission's new policy initiatives geared towards China were formulated after February 24.

In May, at the EU-Japan summit, Brussels and Tokyo pledged to "deepen their deliberations on China, particularly on security."

That same month, Brussels announced that it would hold an "upgraded" trade dialogue with Taiwan in June, a dialogue ostensibly aimed at deepening cooperation between the European Union and Taiwan in the field of semiconductor manufacturing.

Indeed, it was a signal that the EU was willing to reopen discussions on strengthening ties with Taiwan regardless of China's reaction: this proposal was previously floated in late 2021, but was scrapped for fear of a backlash from Beijing.

More initiatives are in the pipeline, which are not explicitly directed against China, but do provide tools for a long-term battle.

EU institutions are negotiating a new mechanism that will allow the bloc to assess industrial subsidies to trading partners and apply countervailing tariffs.

Brussels could certainly use this against China, which has heavily subsidized many domestic export-oriented industries.

This year, the European Commission will put in place another trade mechanism to prevent imports using forced labor from entering the bloc.

This could also create an open tool for trade regulators to double the protectionist pressure on Beijing.

To become law, the European Commission's proposals need the approval of member states.

Before the war, this was the main sticking point.

But later Central and Eastern Europe in particular turned into a hawkish mood, as Russian aggression reminded them of their dependence on the American security umbrella.

Taiwan has strengthened its economic engagement with the region, and eastern European leaders with close ties to Beijing have become increasingly isolated.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán can still hold Brussels hostage over foreign policy votes, where EU rules require consensus, but other initiatives require only a qualified majority.

It is clear that Western European Union members with decades of economic ties to China are now hesitant, but the consensus there is also changing.

Germany's tacit policy toward countries like China, known as "change through trade," lost all legitimacy on February 24.

During a recent tour of Asia - which did not include China - German Chancellor Olaf Schulz called for less German dependence on certain thorny countries, meaning China.

Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi has invoked "golden power" rules to prevent Chinese companies from making takeovers.

With 3% of Italian exports and nearly 8% of German exports destined for China each year, Rome and Berlin are not seeking to discontinue full economic engagement with China, but they will certainly be more accepting of the European Commission's initiatives on China than in the past.

European politics is diverse and complex, with many points of objection.

This makes it difficult for the bloc's foreign policy position to change quickly.

Brussels' initiatives to reduce the bloc's economic and political exchange with China are gaining more force in some EU member states than others, and business groups will continue to work behind the scenes to prevent further indulgence in such exchange.

However, efforts are moving in this direction even before the Ukraine war.

The EU's long-standing assumption that economics can substitute for actual foreign policy in dealing with abusive states now appears to be a bad bet.

Follow our latest local and sports news and the latest political and economic developments via Google news