RFI explains

Che Guevara, a controversial legacy

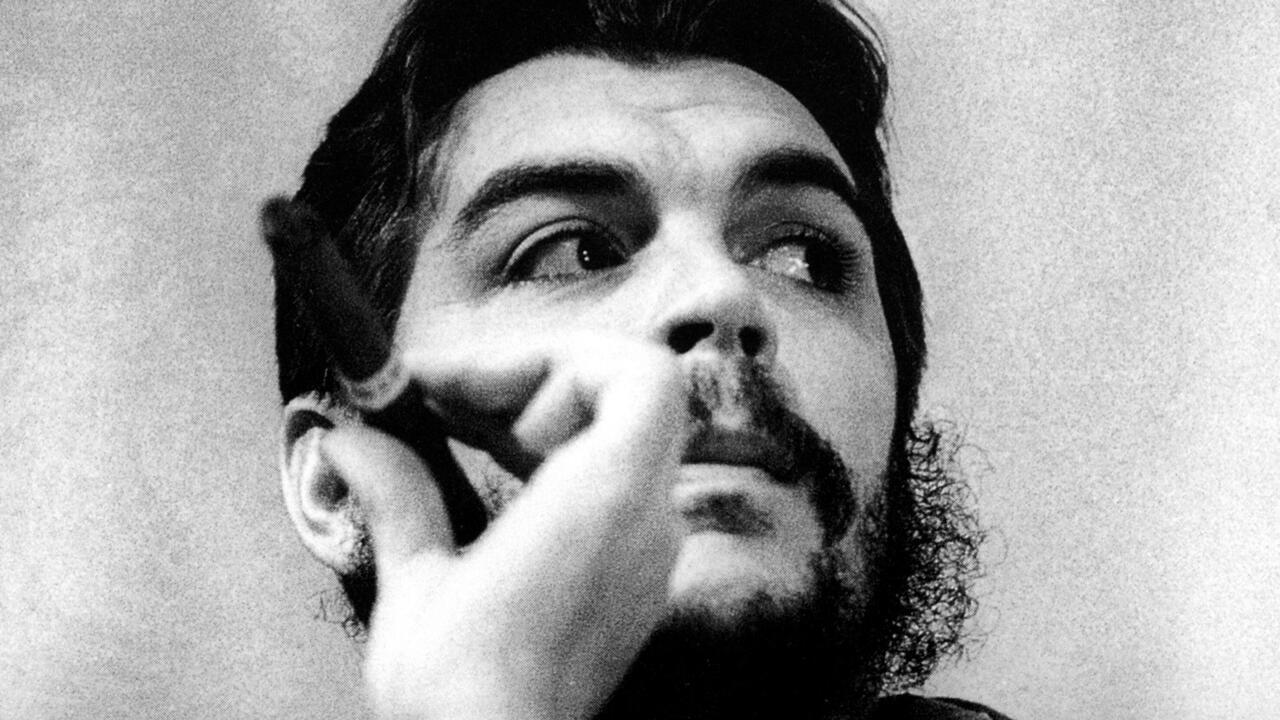

Ernesto “Che” Guevara, doctor and revolutionary, born June 14, 1928 in Argentina and died October 9, 1967 in Bolivia.

© Peter Bischoff/Getty

Text by: MFI

11 mins

On October 9, 1967, Che Guevara was executed by the Bolivian army.

It was the death of the cantor of anti-capitalism, the traveling companion of Fidel Castro, the defender of the Third World, the symbol of the internationalist revolution.

More than half a century later, the character still seduces.

The revolutionary has become a myth with eternal youth, a commercially exploited myth.

Advertising

Read more

Article originally published on 08/10/2007.

Born on June 14, 1928 in Argentina into a middle-class family, Che Guevara – whose real name is Ernesto Rafael Guevara de la Serna – embodies the revolutionary fight in Latin America, the fight against imperialism and the aspiration for solidarity. international movement in favor of oppressed peoples.

A fragile and asthmatic child, little Ernesto was a mediocre student, but he read a lot and made a point of playing sports to overcome his illness.

Its first contacts with the policy are the fact of a communist uncle who takes part in the war of Spain.

Her mother is a feminist and anticlerical activist, which was rare in Argentina at the time.

But the real political revelation for someone who, in the meantime, had become a medical student was the journey he made in the early 1950s through Latin America.

He then discovers misery, social inequalities and the absence of rights for the poorest.

Influenced by his Marxist readings, Che Guevara then considers that only revolution can change this situation.

In 1954, he met in Mexico

Fidel Castro

.

A meeting that will transform the young humanist adventurer into a hero of the revolution.

He joined the Líder Maximo troops in their fight against the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, and established himself as a fierce fighter.

When Batista fell in 1959, Che Guevara became prosecutor of the Revolutionary Court, then Governor of the Central Bank and Minister of Industry of Cuba.

But power and bureaucracy bore him;

he criticizes the omnipresence of the USSR;

Fidel Castro is wary of his popularity.

In 1965, Che Guevara resumed his pilgrim's staff of the revolution, going to defend his internationalist ideas – sometimes with arms in hand – first in the Congo, then in Bolivia from where he hoped to generalize the guerrilla warfare to all the Andean countries.

Badly prepared, the operation is a disaster.

Che Guevara is captured,

then executed on October 9, 1967 by the Bolivian army, then trained by the CIA.

The one who was a hero of the revolution then becomes an icon for Marxist movements and young people in search of revolutionary ideals.

His charisma transcends the failure of communist regimes

Like any myth, that of Ernesto Guevara has an irrational dimension.

More than fifty years after his death, the man is known and popular all over the world.

It embodies the ideal of a pure revolution, without compromise.

Died at 39, he still appears young, although he would be over 90 today.

Numerous books, documentaries and exhibitions have been devoted to him, as well as a film –

Carnets de voyage

– which retraces his first journey to Latin America.

Songs to his glory have even been composed.

The American weekly

Times Magazine

ranked him among the 100 most important personalities of the 20th century.

His charisma transcends the failure of communist regimes around the world, even that of Cuba.

A year after his death, thousands of American protesters against the Vietnam War wear t-shirts bearing his image.

During the events of May 68 in France, students chant "Ho-Ho-Ho Chi Minh!"

Che-Che-Guevara!

The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre proclaims: “

Che Guevara is the most complete human being of our time

.

The appeal launched by the Argentinian revolutionary – “

Create two, three…, many Vietnams

” – in favor of the liberation of the occupied countries met with a very strong echo among Western youth.

In his book

Che Guevara, itinerary of a revolutionary

, Loïc Abrassart writes:

Che offers the model of a renewed communism, freed from the shackles of the real socialism of the countries of the East.

It's the Cuban sun against the Soviet greyness.

He remains a powerful symbol of rebellion and social justice.

Even today, posters of Che adorn the bedrooms of teenagers in search of the ideal.

In Cuba, the person concerned is the object of quasi-religious veneration.

The mausoleum where he rests, in Santa Clara, attracts thousands of visitors every year, including many foreigners.

His statue decorates several public places and factories.

Every morning, school children sing: “

Pioneros por el comunismo, Seremos como el Che

” (“

Pioneers of communism, we will be like Che

”).

beers and condoms

It is undeniable that, in part, the myth was developed by the commercial dimension it takes on;

the image of this cantor of anti-capitalism – and Che's adversaries do not fail to ironize about the phenomenon – indeed generates millions of dollars.

T-shirts, watches, caps, coffee cups… The effigy of Che Guevara can be found on all supports.

In 2003, the Luxembourg investment bank Dexia chose it as the emblem of an advertising campaign with

the slogan “Combating received ideas

”.

The image of the revolutionary with the starry beret was used to sell beers and condoms, ice cream and insurance contracts, bicycles and Internet subscriptions.

Certainly he is not the only one in this case.

The diversion of protest figures – like Lenin or Gandhi – corresponds to an ingrained advertising strategy.

“

In forty years, no image has been used, adapted, manipulated, recycled, mythologized or emptied of all meaning as much as that of Che.

Everyone has appropriated it: political activists, artists like Andy Warhol and his pop-art, journalists, fashion designers, merchants of all kinds

, "explained, in the magazine

Vanity Fair,

the director of a London art gallery.

Defenders of the memory of Che Guevara regret that this commercial use weakens his political message.

But they point out that this also testifies to its popularity and that this use was never wanted by the person concerned.

For the adversaries of Che, this glorification of man, his messianic dimension are unbearable.

They recall that, far from being a humanist with generous ideas, Che Guevara approved hundreds of executions by the revolutionary court of Havana.

He himself wrote: “

The executions are a necessity for the people of Cuba, and also a duty imposed by this people.

He is also at the origin of the camps of rehabilitation through work, of sinister reputation, which still exist in Cuba.

Finally, Che Guevara was a poor Minister of Industry, obstinately for ideological reasons in policies doomed to failure.

On this point, however, the American embargo also explains the ruin of the Cuban economy.

No offense to its detractors,

the cult of Che

remains a reality.

Two photos have largely contributed to this.

That of Che Guevara on his deathbed, his eyes wide open, his face peaceful, the look of a martyred Christ, the image of a Saint of the poor and oppressed, now sacrificed.

Even more famous is the photo taken by Alberto Korda of Che looking proudly into the distance, his starry beret on his head;

the most reproduced cliché in the world, immediately recognizable as the Mona Lisa can be.

About him, the publicist Jacques Séguéla wrote in the magazine Photo: “

Korda's photography concentrates all the virtues attributed to Che: honesty, bravery, selflessness, challenge, loyalty, pride, without forgetting a dose of military virility.

Che Guevara's face expresses as much firmness (facing the United States) as confidence (in the future of the revolution), negligence (beard, long hair in the wind) as serious commitment

(the star commander on his beret)

”.

Returning the United States and the USSR back to back

According to Ariel Dorfam, professor of political science at Duke University (USA): “

We live in a time of fierce competition and fierce consumerism.

The world is marked by a march forward towards money and material goods.

Utopias are buried, but we are always in search of meaning.

We are looking for heroic values that Che Guevara embodies with his mixed culture, his nomadic allure, his refusal to compromise, his contempt for comfort, his eternal youth, his demand for justice on a global scale.

An analysis shared by Loïc Abrassart: “

At the beginning of a century devoid of a collective project, characterized by neoliberal globalization, Che is the stuff of dreams.

The absence of an alternative ideology to capitalism after the collapse of the authoritarian regimes of the East leaves a void to be filled.

The figure of Che is called to the rescue of a world orphaned by protest thinking that has not been compromised by the dramatic results of countries claiming socialism.

»

The strength of Che is to have always believed in the revolution, to have always defended the colonized countries and to have ended up dismissing back to back the United States and the USSR as responsible for the oppression of the Third -world.

Its strength is also not to be associated with power and its baseness in the collective unconscious.

This is the thesis defended by Christopher Hitchens, who was a fervent advocate of the Cuban revolution in the 1960s before turning his back politically:

Admiration for Che Guevara today takes on a romantic dimension that obscures his political ideas.

His personality is complex;

he was both exemplary and arrogant, provocative and thoughtful, ruthless and humanist, idealist and extremist, communist but free spirit, ideologue but devoid of any diplomacy and political calculation.

These contradictions are seductive.

Che's iconic status comes from the fact that he failed.

His story is a story of defeat and isolation.

He is a revolutionary who no longer has either claws or fangs;

he embodies a revolt that hurts no one.

Had he lived longer, had he been associated with power, the myth of Che would have died long ago.

»

The construction of a “new man”

The era is no longer one of revolution, and the fall of the Soviet bloc in 1979 sounded the death knell for a certain communist ideology.

In Cambodia, the genocide perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge has discredited the idea of a revolution that wipes the slate clean, of the construction of a “new man”, of a third world that frees itself from its yokes.

The countries that still claim Marxism – North Korea, Cuba, Laos – are neither models of democracy nor examples of economic success.

The very style of Che Guevara – refusal of compromise, fight until death, absolute ethical requirement – does not have much success.

Vietnam – cited as an example by Che – is certainly still officially a communist country, but largely integrated into the global economy, like China.

Nevertheless, "Guevarism" is not dead.

In the 1990s, the failure of neoliberal reforms in Latin America revived some of Che's political views, such as Pan-Americanism, popular fronts, and the nationalization of key industries.

Similarly, the absence of strong opposition to the liberal globalization that is everywhere is resuscitating interest in his ideas.

Some see in the alterglobalists the heirs of Che Guevara.

In Latin America, many guerrillas

are inspired by "Guevarism".

This is the case in Peru of the Shining Path, of sinister reputation and today decimated;

in Colombia, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), who are not only the kidnappers of Ingrid Betancourt, but also the supporters of a peasant revolution;

finally in Mexico, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, led in Chiapas by Subcomandante Marcos, refers to the Argentine revolutionary.

Admittedly, none of these guerrillas won their fight, nor even found widespread popular support.

In addition, Hugo Chavez, Venezuelan president who died in 2013, often gave his speeches wearing a t-shirt bearing the image of Che.

Evo Morales, former Bolivian president, regularly paid tribute to Che Guevara in his speeches and had a portrait of his hero installed, made of coca leaves, in the presidential suite.

Symbolic gestures which however do not constitute a policy.

Newsletter

Receive all the international news directly in your mailbox

I subscribe

Follow all the international news by downloading the RFI application

google-play-badge_EN

Story

Cuba

Bolivia

Venezuela