Amidst the people's distrust of promises

Somalia elects new president amid real terrorist challenges

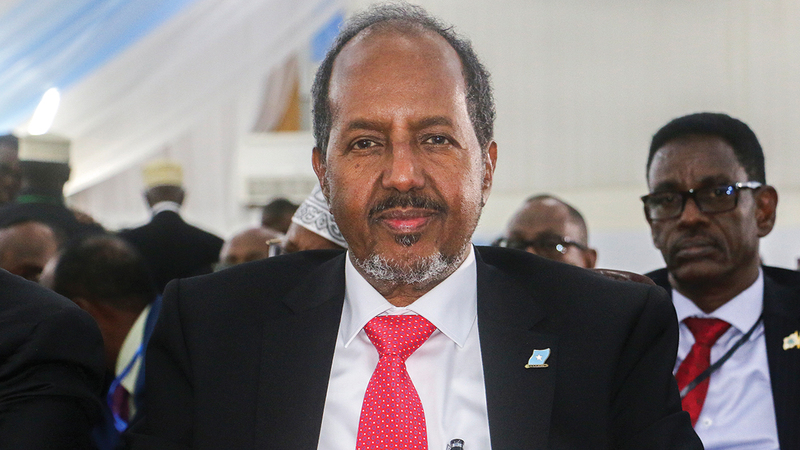

President Hassan Sheikh Mahmoud after being sworn in.

EPA

Thousands have been displaced and are staying in tents due to food shortage conditions in Somalia.

archival

picture

In a fortified tent manned by peacekeepers, hundreds of Somali parliamentarians elected a new president for Somalia last Sunday, capping a violent election season that nearly plunged the Horn of Africa into the abyss.

The election of President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, a former president of Somalia, in Mogadishu, the capital, brought an end to a bitter election period marred by corruption, the president's attempt to cling to power and violent street fighting.

President Mahmoud was able to defeat about 30 candidates after three rounds of voting, including President Muhammad Abdullah Muhammad, who was criticized after he extended his presidential term last year.

The vote, which was delayed nearly two years, came amid soaring inflation and a deadly drought that left nearly 40% of the country's population starving.

Streets were closed in Mogadishu on Sunday, and police declared a curfew until Monday morning.

Shouts of jubilation and ululation erupted in the tent where members of Parliament met, after Mahmoud's victory in the presidency was announced.

Shots were fired in the streets of the capital, according to some witnesses.

Earlier, several explosions could be heard from the tent where the voting was taking place, but they did not lead to a halt in the process of electing the president.

"Our country needs to move forward," Mahmoud said after his election.

Youth Organizing Challenges

Mahmoud, 66, will face a host of challenges during his four-year rule, particularly the power of al-Shabab, a terrorist group that has a strong grip on large parts of the country.

Somalia's population of nearly 16 million has endured civil war, weak governance, and terrorism for decades.

The central government in Mogadishu is backed by the African Union peace forces and Western aid, including several billion dollars in humanitarian and security assistance from the United States, which has sought to prevent Somalia from becoming a haven for terrorists.

The president was elected by 328 members of parliament, elected through clan representation.

Mahmoud won 214 votes, while former President Mohamed won 110 votes.

Few of the votes were spoiled, while one voter was ill and did not participate in the election.

Mahmoud assumed the presidency from 2012 to 2017, and was born in the Hiran region, central Somalia.

A peaceful activist and teacher, he founded a college that became the largest in Somalia.

Experts said that al-Shabab, which is linked to al-Qaeda, has taken advantage of political instability in Somalia and the bitter division between security forces to expand its control and gain more power.

After nearly 16 years, the organization now possesses wide powers, as it collects taxes, organizes trials, forces minors to join its fighters, and carries out suicide bombings.

In the weeks leading up to the voting and the election of the president, al-Shabab killed civilians including diners on the beach, carried out major attacks on African Union peacekeepers, killed 10 of them from Burundi, and carried out suicide bombings in government officials' cars.

deteriorating situation

Dozens of citizens, members of parliament, analysts, diplomats, and aid workers expressed in multiple interviews before the elections their concern over the deteriorating political, security and humanitarian situation in Somalia, which lived a few quiet years after the expulsion of al-Shabab from the capital in 2011.

Observers say that the long-running political battles, especially over the elections, have undermined the government's ability to provide basic services, even after debt relief and its attempt to join the global financial system.

Opponents accused former President Muhammad of trying to maintain power at all costs, as he put pressure on the electoral commission, appointed government officials to help him impose his authority on the elections, and tried to fill parliament with figures from his followers, using the intelligence services.

Last year, he signed a law extending his term of office for two years, and fighting erupted in the capital's streets, forcing him to repeal this law.

Observers said that the election of parliament members last year was marred by a lot of corruption.

Bad Parliamentary Elections

Abdi Ismail Samater, a Somali parliamentarian, a professor at the University of Minnesota, and a researcher in the field of African democracy, said that the parliamentary elections last year were “the worst in the history of Somalia.” He added, “I never imagined that corruption would engulf the Somali elections to this extent.” In Somalia, Larry Ender, the majority of seats in parliament were chosen by local leaders and were "sold".

Given the indirect nature of presidential elections, candidates do not campaign in the streets.

Instead, they meet with members of parliament and tribal leaders in luxurious hotels and compounds guarded by soldiers.

Some candidates publish banners with slogans promising good governance, justice and peace.

But few in Mogadishu are satisfied with such pledges.

"Everyone wears pretty suits and makes sweet promises like honey, but we don't believe them," said Jamila Adnan, a student who studies political science at City University.

Given the infighting and government paralysis, many Somalis wonder if the country's new administration could make the difference for Somalis.

Switching to Youth Courts

Some Somalis have turned to get services from Al-Shabab, and many Somalis travel to areas tens of miles north of them to solve their cases in the Mobile People’s Courts, and one of these Somalis is the businessman, Ali Ahmed, who is from a tribal minority whose family home in Mogadishu was occupied, from Many years ago, members of a powerful tribe.

Ahmed said that the Youth Organization Court ruled that the people occupying his family's home should leave it immediately, and that's what they did.

“It's sad, but no one goes to the state courts, and government judges are secretly telling you to go to the youth organizing courts,” Ahmed said. Merchants pay their taxes to the youth, fearing a threat to their business and their lives.

Some government officials acknowledged the government's shortcomings, and the youth organization worked to expand its tax base, because elected officials were preoccupied with politics rather than managing people's affairs, according to one government official, who declined to be named because he was not authorized to do so.

Worst drought in decades

Last Sunday's elections came at a time when part of Somalia is facing the worst drought in four decades, and about six million people suffer from severe food shortages, according to the World Food Program, while 760,000 have been displaced from their homes.

About 900,000 of those affected by food shortages live in areas controlled by Al-Shabab, according to the United Nations, so aid organizations cannot reach them, crops have spoiled, and Al-Shabaab demands taxation of livestock, according to interviews conducted with officials and people displaced from their homes.

To find food and drinking water, families travel hundreds of miles, sometimes on foot, to cities and towns such as Mogadishu and Doula, in southern Somalia's Gedo region.

Some parents said they buried their children on the road, while others said they left their vulnerable children behind, to save others who are stronger to walk.

The Executive Director of the Heritage Institute for Political Studies in Mogadishu, Aviar Abdi Elmi, says that dealing with the youth organization is one of the most important challenges facing the future Somali government, and Abdi adds that the new president also needs to draft a new constitution aimed at economic reform, dealing with climate change, and opening Dialogue with the Somaliland region, which is separated from the state with the aim of uniting the state, and he said, "Governance in Somalia has become difficult during the past years, and people are now ready for a new dawn."

• Mahmoud, 66, will face a set of challenges during his four-year rule, especially the power of al-Shabab, a terrorist group that has a strong grip on large parts of the country.

• Observers say that the long-running political battles, especially over the elections, have undermined the government's ability to provide basic services, even after debt relief and its attempt to join the global financial system.

• About six million people suffer from severe food shortages, according to the World Food Program, while 760,000 have been displaced from their homes. About 900,000 of those affected by food shortages live in areas controlled by al-Shabab, according to the United Nations.

Abdi Latif Daher ■ The New York Times correspondent in East Africa

Follow our latest local and sports news and the latest political and economic developments via Google news