Miscalculating someone's age can be embarrassing, especially when the amount of error is a few billion years!

This may be the case with our Milky Way, suggests research published on March 23 in the journal Nature. In the new study, scientists extrapolated the ages of nearly 250,000 stars in the Milky Way using brightness and location data. and the chemical composition collected by two powerful telescopes: the European Space Agency's (ESA) Gaia orbital observatory, and the LAMOST Wide Field Multi-Objective Fiber Spectral Telescope (LAMOST) in China.

2 billion years error

A report on the "Live Science" website - published on March 28th - states that the research team discovered that thousands of stars in a part of the Milky Way known as the "thick disk" began forming about 13 billion years ago, i.e. About 2 billion years earlier than expected, and only 0.8 billion years after the Big Bang.

"Our results provide fascinating details about this part of the Milky Way, such as when it formed," said study lead author Maosheng Zhang, an astrophysicist at the Max-Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, in a press release published by the European Space Agency. , the rate of star formation and the history of their mineral content,” he says, adding: “Putting these discoveries together – using Gaia data – will revolutionize our perception of when and how our galaxy formed.”

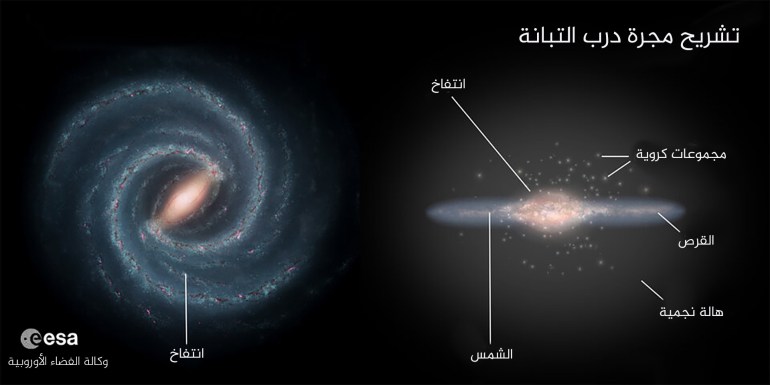

The Milky Way is a spiral galaxy with a diameter of about 105,000 light-years, but not all parts of this spiral shape are the same in thickness, composition, or stellar density;

Near the center of our galaxy is a massive bulge of stars (and possibly a supermassive black hole holding the galaxy's gravity together), and the galactic disk stretches on either side of this bulge, and is made up of two main sections.

Anatomy of the Milky Way (ESA)

One side of the "thin disk" contains most of the stars we can see from Earth, mixed with clouds of star-forming gas, while the "thick disk" is twice as high as the thin disk, but has a much smaller radius and contains only a small portion of the stars we can see. In the sky, according to the European Space Agency, this part of the Milky Way is also believed to be much older, devoid of gas, and where star formation has ended.

semi-giant star

In their new study, the researchers looked at stars throughout the Milky Way, focusing on a particular type of star called "quasi-giant stars," which are stars that have stopped generating energy in their cores and slowly turn into red giants (massive stars on their way to collapse into white dwarfs), and the "semi-giant" phase is a relatively short period of stellar evolution, which means astronomers can estimate the ages of these stars more accurately, according to the researchers.

Since older stars tend to glow in a certain range of brightness and have lower metal content (elements heavier than hydrogen and helium) than modern stars, the team was able to date their star sample by processing data from both telescopes through computer simulations. The researchers found that the stars in the galaxy's thick disk were actually much older than the stars seen elsewhere, and surprisingly, those stars were billions of years older than previous studies suggested.

This discovery could rewrite the history of our galaxy (Getty Images)

According to the researchers, this discovery could rewrite the history of our galaxy, as the age differences between stars in the thin and thick disks indicate that our galaxy formed in two separate phases;

First, 0.8 billion years after the Big Bang, star formation began in the thick disk, then star formation accelerated dramatically about two billion years later when a dwarf galaxy called Gaia Sausage collided with our young galaxy, which started the second stage. From the evolution of the galaxy, when the thick disk rapidly filled with stars, while the first wave of star formation began in the thin disk.

The study authors hope to fill in the details of this story further, after the release of the third dataset of Gaia in June.

"With each new analysis and data release, Gaia allows us to continue writing the history of our galaxy in more detail than ever before," Timo Prosti, a European Space Agency's Gaia project scientist who was not involved in this study, says in the statement.