Introduction to translation

This report reviews nearly 50 years of scientific research on a single neuroscience experiment aimed at answering a specific question: Do we really have free will, or are our decisions predetermined?

In fact, one of the main problems faced by the Arab debate on issues such as consciousness or free will is that it ignores what neuroscience offers in it, and resorts directly to the scope of philosophy, so we have found it necessary to show, from time to time, how neuroscientists discuss In the same case.

translation text

The concept that humans do not have free will because their decisions are predetermined has been popular since 1964, when two German scientists conducted an experiment in which they monitored neural activity in the brains of dozens of people.

The experiment lasted for several months, during which volunteers came daily to the laboratory at the University of Freiburg to install the electrodes on the scalp. The participants’ task was to sit and bend one of the fingers of their right hand whenever they wanted to at irregular intervals, and they continued to do this repeatedly until they reached 500 times in One visit.

The purpose of this experiment was to look for neural signals in the participants' brains that precede each finger flick.

It's true that researchers had previously figured out how to measure neural activity that occurs in response to external events - such as when someone is listening to a song - but what no one has been able to figure out is how to identify these brain signals that arise when a person actually initiates an activity.

This wave of neural activity that scientists called a "bereitschaftspotential" was a gift for time travel.

(wikipedia)

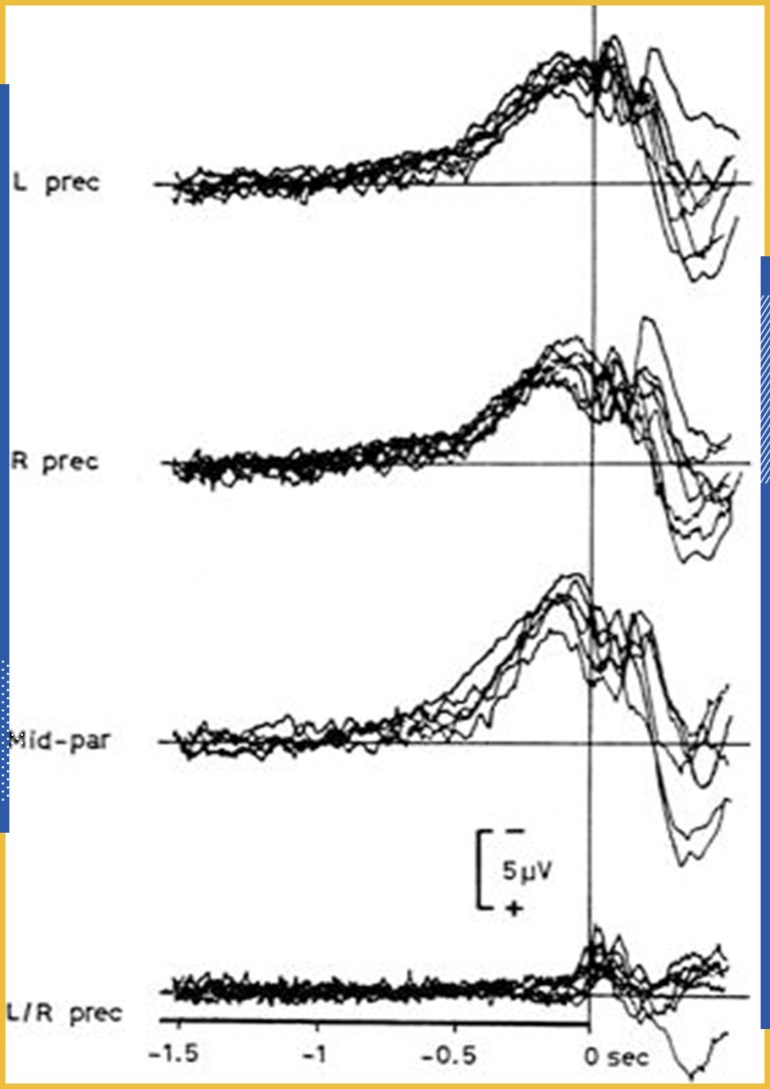

The results of the experiment appeared in the form of zigzag and dotted lines representing the changing nerve waves.

Less than a second before the participants moved their fingers, the streaks showed a very faint, hard-to-distinguish spike, a wave that rose for about a second, then quickly ended in a sudden dip.

This wave of neural activity that scientists called a "bereitschaftspotential" was a gift for time travel.

For the first time, scientists have been able to read the brain as it prepares to create voluntary movement.

the beginning of trouble

This landmark discovery was the beginning of much trouble in neuroscience.

After twenty years of this experience, the American physiologist "Benjamin Libet" used this discovery to prove that the brain not only shows signs of making a decision before a person makes it, but that our conscious decisions are predetermined in our neurons before we even realize them.

Suddenly it seemed that human brains were in charge of things behind the scenes, even the simple flick of their fingers predetermined by causes beyond our control.

Benjamin Libet

Philosophy's biggest question remained, "Are human beings really masters of their own actions?"

Philosophers have been baffling for centuries before Benjamin Libet even steps into the lab.

But what distinguished the Libet experiment and gave it wide fame was that he presented arguments against free will based on neuroscience, and his discovery led to a new wave of controversy in the circles of science and philosophy.

Over time, the results of his experiments became cultural traditions.

The idea that our brains make decisions before we even realize them is popular today among people and in popular newspapers and magazines.

Famous thinkers such as American neuroscientists Sam Harris and Yuval Harari often cite the Libet experiment, claiming that science has shown that humans are neither masters of their own actions nor responsible for their decisions.

The term “predisposition” was not intended to provoke debate about free will. On the contrary, when German neuroscientist Hans Helmut Kornhuber and his doctoral student Lord Dick first discovered this concept by conducting their aforementioned experiment, their primary aim was to show that The brain has a kind of will, due to their extreme frustration with the passivity of scientific research prevalent in their time that treated the brain as a mere deaf machine for producing thoughts and actions in response to the outside world.

So in 1964, the two German scientists decided one day over lunch to try to figure out how the brain works to generate action automatically. "Kornhuber and I both believed in free will," says Dick, now 81.

To accomplish the experiment, the duo had to devise tricks to outsmart the limited technology of the time.

Although they had a modern computer that measured the participants' brainwaves, it didn't show any results until after the participants moved their fingers.

Faced with this problem, the researchers realized that they needed to discover a trick that would enable them to collect data about what happened in the brain previously, so both of them resorted to recording neural activity separately on a tape, and then playing this tape in reverse on the computer.

Dubbed inverse averaging, this innovative technique revealed the potential for preparedness (the brain's willingness to work well before we even realize the urge to act).

This discovery received a lot of attention from the world, and many scientists referred to this study, including the Nobel Prize-winning physiologist John Ackles, and with him the famous philosopher of science Karl Popper, who compared the ingenuity of this study with the experience of the Italian astronomer Galileo, who used sliding balls to detect The laws of motion of the universe.

Kornhuber and Dick similarly did the same with the brain using a handful of electrodes and a recording device.

In fact, anyone can guess what “readiness potential” means. If we imagine, for example, that neural activity in the brain resembles dominoes, the rising waves of brain activity are the falling dominoes one by one towards a person who is starting to do something.

The scientists explained that the "readiness potential" is the electrical signal or activity that the brain shows when planning and starting to make a voluntary movement.

As we can see, this idea tacitly assumes that it is the possibility of being prepared that causes us to actually rise.

At the time, this assumption seemed very natural and logical, so no one tried to challenge the validity of this hadith.

Half a second before the decision

In the 1980s, Benjamin Libet, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, sparked the debate about "readiness" by asking why it takes 500 milliseconds between the decision of volunteers to move their fingers and actually doing so?

So he repeated Kornhuber and Dick's experiment, but asked the participants to watch a device that looked like a clock so they could remember the moment they made the decision.

The results showed that electrical activity (or readiness) occurred 500 milliseconds before participants moved their fingers, as well as that participants did not know their intention to move their fingers until 150 milliseconds before the actual movement, which led to the conclusion that the brain decided what to do before That the participants be aware of this.

On the other hand, many scientists objected to Libet's conclusion, saying that it is inconceivable that our conscious awareness is an illusion, or that our actions are nothing more than accidents that occur after our brains make a decision.

The researchers also questioned the accuracy of the tools used in the experiment and how accurately participants remembered when they made the decision.

Despite all these skepticism, it has been difficult for researchers to pinpoint the shortcomings accurately.

Libet died in 2007, leaving no fewer supporters of his experience than critics, and in the decades since his study, many researchers have repeated his experiment using newer techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, but interestingly, no one disputes the possibility that what Libet saw was not It was not accurate, but the argument revolved around the possibility that his conclusions were based on an incorrect premise.

Although some noteworthy studies have asked what would happen if preparedness was not the main reason for our decisions, unfortunately they failed to provide any evidence for the function of these nerve signals.

To settle this wide debate, someone had to offer an alternative explanation.

In 2010, Aaron Schorger, a researcher at the National Institute of Health and Medical Research in Paris, studied fluctuations in neuronal activity that arise from the spontaneous flickering of hundreds of thousands of interconnected neurons, and concluded that the noise generated by neuronal activity keeps rising and falling in a similar way. Tidal movements that occur on the surface of the ocean.

Commenting on this, Schorger says: "Any phenomenon that comes to my mind I find it behaves almost in this way, such as the chronology of stocks in the financial markets, or the changing weather."

Next, Schurger thought that if he decided to focus on the ripple crests of a phenomenon (such as thunderstorms, or market records), and then reverse their mean on the innovative Kornhuber and Dick method, the results would continue to be upward (i.e. peaking as the weather intensified) weather disturbances, or a rise in stocks in the financial markets).

From here we conclude that there will be no purpose behind these trends, as there is no previous plan to cause a storm or to raise stocks.

These patterns simply reflect the way in which various factors can coincide and coincidentally combine to create a situation.

Schurger concluded that if he applied the same method to neural noise in the brain, he would get a signal of "possibility," and realized that this rising pattern (neural activity shown on the screen) was not a sign that the brain was running the reins at all (rather rather randomly). about continuous spontaneous fluctuations in nervous activity).

Two years later, Schürger and fellow neuroscientists Jacobo Seit and Stanislas Dehaene offered an explanation.

Neuroscientists argue that when we have to make a decision based on visual input, groups of neurons start accumulating visual evidence in favor of potential outcomes, and eventually one makes the decision when the evidence for a particular outcome becomes strong, sometimes relying on sensory information from the world exterior.

If you are watching snowfall, for example, your brain will compare the large amount of snow falling down and the little snow that has flown in the wind, and it will be guided by the fact that it is snowing down.

But Libet's experiment, Schorger sees it, did not provide participants with such external cues (visual clues), but rather relied on the participants' decision to move their fingers when they wanted to, and time their decision based on that desire.

Schurger argues that these spontaneous moments must have coincided with the constant random fluctuations of neural activity in the participants' brains, making the participants more likely to move their fingers when their motor system was about to start moving.

Libet's belief that people's decisions are predetermined in the subconscious before they realize it is a misconception, because the disturbed neural activity in people's brains (neuronal oscillations) sometimes happens to tip one choice over the other, saving us from endless frequencies when faced with tasks of interest. Lots of random options.

In this case, the 'readiness potential' would appear as a rising tide of random fluctuations in neural activity that tend to coincide with decision-making.

What we are talking about is a very special case and cannot be generalized.

In another study of monkeys tasked with choosing between two equal options, a team of researchers saw that the monkeys' next choice was linked to the internal activity of their brains before they were even presented with the options.

In a second study still under review at the US National Academy of Sciences, Schurger and two researchers at Princeton University repeated Libet's experiment, but they took more precise measures and used the latest artificial intelligence techniques to find the two points at which there was a change in brain activity (that is, before the decision was made). participants and after they decide).

And here's the surprise: the AI algorithms didn't show any change until about 150 milliseconds before actual movement, which is the time people reported making decisions in the original Libet experiment.

In other words, it appears that people's personal experience of making decisions is not just an illusion, as Libet's study showed, but rather corresponds to the actual moment in which our brains report that they are making the decisions.

When Schürger first proposed the explanation for neural noise in 2012, the paper didn't get much outside attention, but it did create a buzz in the field of neuroscience, and Schürger won awards for his ability to disprove a long-held idea.

“Recent studies have shown that preparedness is not what we thought it might be, but in a way it appears to be related to how we analyze our data or [visual input],” says Ori Maus, a neuroprogramming scientist at Chapman University in California.

Like any new idea, Schürger's study initially encountered some resistance, but what distinguishes it from other previous studies that have repeated Libet's experiment and come to nothing is Schorger's approach to testing causation.

What everyone agrees on today, whether they support or oppose Libet's experiment, is not to rely on the concept of "possibility of readiness" in their experiments.

(A few who still hold the same traditional view admitted that they had not yet read Schurger’s paper published in 2012) In the same vein, “The studies Modernity has reopened my horizons.

In spite of all that Schürger has found, the percentage of him being wrong still exists, because the deductive nature of the brain always leaves the door open for completely different interpretations in the future. Libet did, but it only deepened the question, asking again: Is everything we do predetermined by a series of genetic and environmental causes and effects, and the cells that make up our brains?

Or can we freely choose our decisions and intentions that influence our actions?

The answer to this question is very complex, but if Schurger's bold refutation of Libet's ideas is any indication, it is indicative of our need for more precise and enlightened questions.

“Philosophers have been discussing free will for thousands of years, and they've been making progress until neuroscientists have got themselves into the problem claiming they've solved it in one fell swoop,” says Ori Maus, a neuroprogramming scientist at Chapman University.

In March 2019, an inaugural conference for the first intensive research collaboration between neuroscientists and philosophers was held at which attendees discussed plans for designing philosophical experiments, and unanimously agreed that the different meanings of "free will" should be defined.

In the end, we must be well aware that despite Libett's firm stance on his interpretation of his study, he still believed that his experience was not sufficient to prove the full determinism of the notion that whatever we decide is not subject to our will.

In 2004, he published a book in which he says: "Given the importance of the issue and the extent to which it affects our view of ourselves and the world around us, the claim that our free will is an illusion must be based on some direct evidence, and such evidence is unfortunately not available." .

___________________________________

Translation: Somaya Zaher

This report is translated by The Atlantic and does not necessarily reflect the Medan website.