On June 3, 2017, FBI agents arrived at the home of government contractor Realty Winner in Georgia, where they have spent the past two days investigating a top-secret document allegedly leaked to the press.

Investigating agents claim that in order to track Weiner they carefully studied copies of the document provided by the online news site The Intercept, and noticed wrinkles indicating that the pages had been printed "from inside a government facility and manually smuggled".

In an affidavit, the FBI alleges that Weiner admitted to printing the NSA report and sending it to The Intercept, and shortly after the leak story was published, the charges against Weiner were made public.

The printers use the code

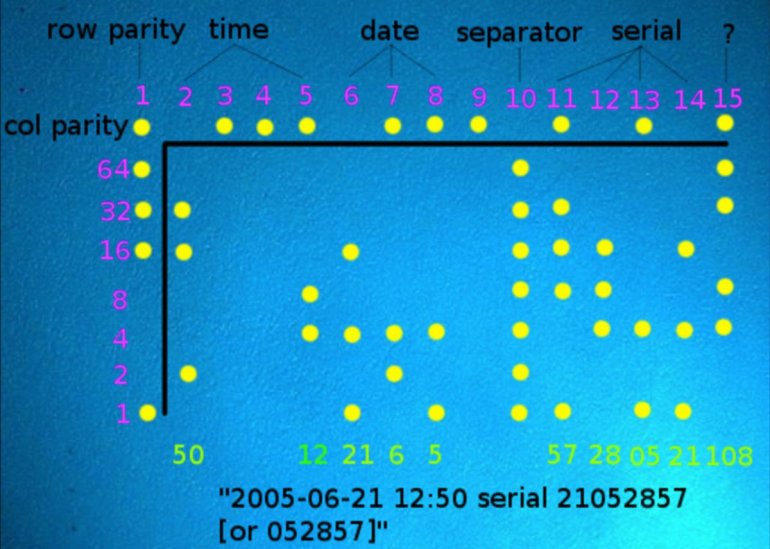

Many color printers add “tiny” microscopic dots to documents without people even knowing they are on them, so experts began taking a closer look at the document, where they discovered something else of interest: yellow, roughly rectangular dots that repeat all over the page. It was barely visible to the naked eye, but it formed a cryptic design.

After a quick analysis, they seemed to reveal the exact date and time to print the pages in question (06:20 on May 9, 2017), possibly the time on the printer's internal clock at that moment.

The dots also encode the printer's serial number.

These microdots are so well known to security researchers and civil liberties activists that many color printers add them to documents without people even noticing they are on them.

"By zooming in on the document, it was very clear ... it's interesting and noteworthy that these things are there," says Ted Hahn of Document Cloud, who was the first to notice these dots.

Another observer was security researcher Rob Graham, who posted a blog post explaining how to identify and decrypt dots, explaining that based on the locations they were printed on the paper, they indicated specific hours, minutes, dates, and numbers.

Several security experts who have decrypted the dots have come at the same date and time as the print.

Color printers have been using these tiny dots for several years, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) maintains a list of color printers known to use this coding method.

The following image, which was captured by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, shows how to decode it:

A tool that reveals information from points

In addition to this method that may be of interest to spies, point coding has other uses, says Tim Bennett, a data analyst at the software consulting firm Vector 5 who also examined the leaked Defense Department document.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation has an online tool that reveals the encrypted information in the form on the printed paper, and people can use this form to check for fraud, so if they get a document and someone says it is from 2005, with this tool they can tell that it is recent printing.

Cryptography on paper since World War II

The NSA points to a great example of the use of dots that make up messages since World War II, when German spies were found in Mexico who had drawn dots inside an envelope to conceal a memo for German military contacts in Lisbon.

At the time, these spies were working in the dark, trying to get materials from Germany, such as radios and ink.

However, these messages were intercepted by the Allies, and the mission was disrupted.

And the little dots the Germans used were often just bits of miniature deciphered text the size of a whole point.

Today, anyone can try to use microtext to protect their belongings. Some companies, such as Alpha Dot in the United Kingdom, sell small packets of permanent adhesive filled with pinhead-sized dots and bearing microscopic text containing a unique serial number. Paste these items on your important items, auto parts, or merchandise so that if the police recover the stolen items, they can theoretically use the number to match it to its owner.