Viruses are the most numerous biological entity, and the coronavirus pandemic that has swept the world has caused most people and scientists to focus on viruses like no other in the history of this planet.

And recently, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Britain and the European Institute for Vital Information (EMBL-EBI) discovered more than 140,000 viral species living in the human gut, and more than half of these viruses had never been seen before .

The study, which was published on February 18 in the journal "Cell", includes an analysis of more than 28,000 gut microbiome samples collected from different parts of the world.

The number and variety of viruses the researchers found was amazing, and the data opens new research avenues for understanding how viruses that live in the gut affect human health.

The gut microbiome

The human gut is an incredibly biologically diverse environment.

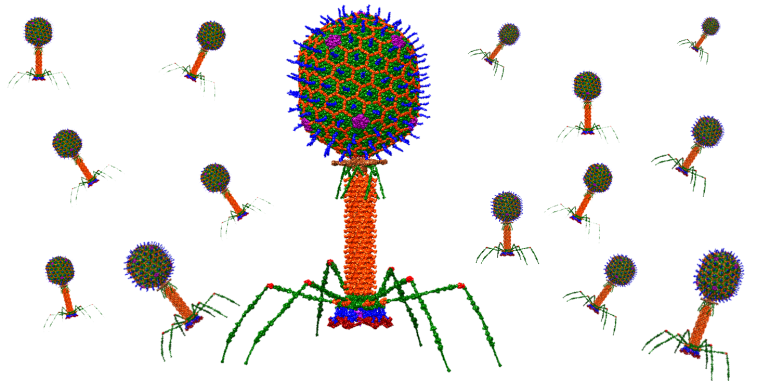

In addition to bacteria, hundreds of thousands of viruses called phages, which can infect bacteria, also live in the human gut.

It is known that an imbalance in the gut microbiome can contribute to complex diseases and health conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, allergies and obesity.

But relatively little is known about the role gut bacteria and phages play in human health and disease.

And if tens of thousands of newly discovered viruses appeared to be a worrisome development, that is perfectly understandable.

But researchers say we should not misinterpret what these viruses represent within us.

In the mysterious environment of the gut microbiome - inhabited by a diverse mix of microorganisms, including bacteria and viruses - phages are thought to play an important role in the health of the human gut itself.

Phages are thought to play an important role in the health of the human gut itself (Spencer Phillips-European Bioinformatics Institute)

Using a DNA sequencing method called metagenomics, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the European Bioinformatics Institute have explored and cataloged the biodiversity of viral species found in 28,601 general human gut genomes and 2,898 cultured bacterial genomes isolated from the human gut.

The analysis identified more than 140,000 viral species that live in the human intestine, more than half of which have never been seen before, and constitute a specific type of virus known as phages, which infect bacteria.

The results formed the basis of the Gut Phage database, a highly structured database of 142,809 phage genomes that will be an invaluable resource for those studying phages and the role they play in regulating the health of both gut bacteria and humans.

Among the tens of thousands of viruses that have been discovered, a new widespread clade - or a group of viruses believed to have a common ancestor - has been identified, which is the most widespread viral class in the human gut.

The analysis identified more than 140,000 types of viruses known as phages living in the human gut (Septalnet-Pixabay).

Came at the right time

The new virus catalog has been published for gut microbiome samples collected from 28 countries, along with nearly 2,900 reference genomes of cultured gut bacteria, and its records are currently available to the public.

These samples came mainly from healthy individuals, says Alexander Almeida, postdoctoral fellow at the European Institute for Bioinformatics and the Wellcome Sanger Institute, in a statement to the recent institute’s news page on the Internet. The gut ecosystem. "

"It is wonderful to see how many unknown species live in our gut, and to try to uncover the link between them and human health," he added.

This high-quality catalog of human gut viruses contributes to guiding future studies (Vectoramos-Wikipedia)

"Bacteria research is currently experiencing a renaissance," said Dr Trevor Lowley, first author of the study from the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The database updates what we know about viral behavior, and the study authors write, "To our knowledge, these results represent the most comprehensive and complete set of human gut phage genomes to date."