This year, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia celebrated the 102nd anniversary of the establishment of their independent republican states, but before these three Caucasian countries emerged into existence, the region was part of the Ottoman and Russian empires, then the Caucasus societies lived a short experience of merging into one state.

In the short period between April 22 and May 22, 1918, the "Transcaucasian Democratic Federal Republic", also known as the Caucasian Federation, was born and included what is now known as Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia, in addition to limited parts of Turkey and Russia, and the federal state lasted only one month. Before Georgia declared independence, Azerbaijan and Armenia followed.

The region that formed the Caucasus Federation was part of the Russian Empire, and the February Revolution of 1917 saw the disintegration of the empire and the formation of a provisional government in Russia.

A similar body was formed in the Caucasus - the Caucasian Special Committee (Ozakum) - but with the October Revolution and the rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia, a Transcaucasia Commission was formed to replace Ozakum.

However, the divergent goals of the three major groups (Armenians, Azeris, and Georgians), the Federal Republic did not have the opportunity to last long, especially in a region surrounded by large empires.

Yerevan Azerbaijani

From the end of the 14th century until the 20th century, Yerevan - the current Armenian capital - and most areas of modern Armenia were predominantly Muslim, most of them belonging to the Turkic and Azeri ethnicities.

By 1832, after the Russian Empire's administration encouraged the settlement of the Armenian population from the Iranian plateau and the Ottoman lands in the region, the country became shared by the Armenians and Muslims, yet Yerevan remained a Muslim majority made up of the Azeris, Turks and Persians.

According to the British traveler Henry Finnice Sher Lynch (1862-1913) who visited the region and wrote two volumes on Armenia published in 1901, the capital was divided between Azerbaijan and Armenians in the early 1990s, while the traveler Luigi Villary indicated in 1905 that the Azerbaijanis were in Yerevan (who noted To them, the Tatars) were more wealthy and owned almost all the lands.

For the Azeris of Armenia, the 20th century was a period of marginalization, discrimination, mass migrations and often forced displacement.

In 1905-1907 Yerevan became an arena for clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, and it is believed that the Russian government instigated them in order to distract the public from the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Tensions rose again after the independence of Armenia and Azerbaijan for a short period from the Russian Empire in 1918, and the two countries quarreled over their common borders, and the war coupled with the influx of Armenian refugees led to large-scale massacres against the Azerbaijanis in Armenia, which led most of them to flee to Azerbaijan and change the ethnic and demographic composition For the Armenian states.

Baku and the Armenians

On the other hand, the Armenians once formed a large community in Baku, the current capital of the Republic of Azerbaijan, although the history of their early settlement is unclear. The Armenian population in Baku swelled during the 19th century, when it became a major center for oil production and provided other economic opportunities for investors. And entrepreneurs, according to the historical reference “Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2004” (Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2004).

The number of Armenians in Baku remained large until the 20th century, despite the turmoil of the Russian revolutions in 1917, but almost all Armenians fled the city between 1988 and early 1990, as only 50 thousand Armenians remained in Baku compared to a quarter of a million in 1988.

In conjunction with the outbreak of ethnic tensions accompanying the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the early stages of the Nagorno Karabakh War.

Baku witnessed a large influx of Armenians after the city was incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1806, and many of them held positions as merchants, industrial managers and government officials, and they created a community in the city that included churches and schools, and they were a model of a living literary culture.

The economic conditions provided by the Russian imperial government allowed many Armenians to enter the flourishing oil and drilling business in Baku.

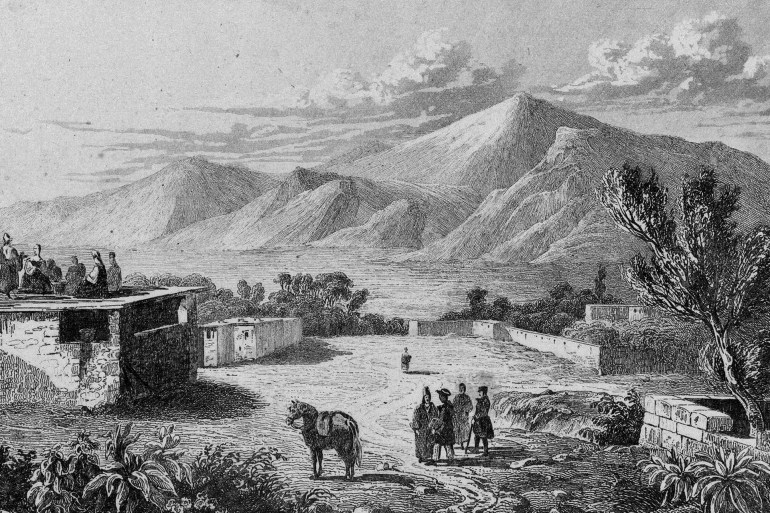

Mount Ararat on the present-day Turkish-Armenian border contained an Azeri village in 1838 (foreign press)

Together with the Russians, the Armenians formed the financial elite of the city, and the local capital was concentrated mainly in their hands, but the growing tensions between Armenians and Azeris (often sparked by Russian officials who feared nationalist movements among their non-Russian ethnic subjects) led to mutual pogroms in 1905-1906, which sowed The seeds of distrust between these two groups in Medina and elsewhere in the region for decades to come, according to the book Identity Politics in Central Asia and the Muslim World by Willem van Schindle and Erik Jan Thorcher.

After Azerbaijan's independence was declared in 1918, the Armenian nationalist Tashnak party became increasingly active in Baku, which was occupied by the then Russian Bolsheviks.

Several members of the governing body of the Baku Soviet Group consisted of Armenians.

Despite their pledge not to participate, the Tashnag mobilized Armenian militia units to participate in the "March Days" massacres against the Muslim population of Baku in 1918, which resulted in thousands of deaths.

Continuous migration

After a few months, the Armenian community itself dwindled, as thousands of Armenians fled Baku or were killed as the Turkish-Azerbaijani army approached (which captured the city from the Bolsheviks).

Despite these bloody events, Armenians - including the Dashnak members - were represented in the newly formed Azerbaijani parliament at the end of 1918, and they had 11 out of 96 members, and in return, the Armenians had 3 delegates in the 80-seat Armenian parliament.

The story of the Armenians did not end in Baku at the time of the First World War. After Azerbaijan became a Soviet, the Armenians were able to re-establish a large and vibrant community in Baku consisting of skilled professionals, craftsmen and intellectuals integrated into the political, economic and cultural life of Azerbaijan.

The community grew steadily in part due to the active immigration of Nagorno Karabakh Armenians to Baku and other large cities, and the Armenian-populated neighborhood of Ermenikend grew from a small village of oil workers to a thriving urban community.

At the beginning of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict in 1988, the population of Baku alone was larger than the population of this region, and they were widely represented in the state apparatus.

Conflict and Federation

As for Georgia, the third country in the Caucasian mosaic, it included, along with the Georgians, other races, the most important of which are the Azerbaijanis, who form the largest ethnic minority in the country since the 11th century, when the Turkish Oguz tribes settled in the south of the country, while the Armenians form the largest ethnic minority in Tbilisi, the current Georgian capital. After they immigrated to it from Armenian regions in the Middle Ages.

After the Russian Revolution, and in the second decade of the 20th century, the disintegration of the Russian Caucasus Army left the Caucasus region almost empty in the face of the advance of the Ottoman Third Army.

In response, the Armenians, Georgians and Azeris tried to create a unified army, and put their forces under the command of a "Military Council for Nationalities" composed of the three peoples, but soon positions differed as the Azeris allied with the Ottoman Empire, while Georgia signed the Poti Treaty with Germany and welcomed a German mission To protect it in 1918.

And since the Caucasian Union lasted for only one month, it did not leave a great common heritage in this period, even in the educational curricula of the three countries that focus on each country's steps towards becoming an independent state, and sometimes ignore the experience of the transnational Caucasian union.