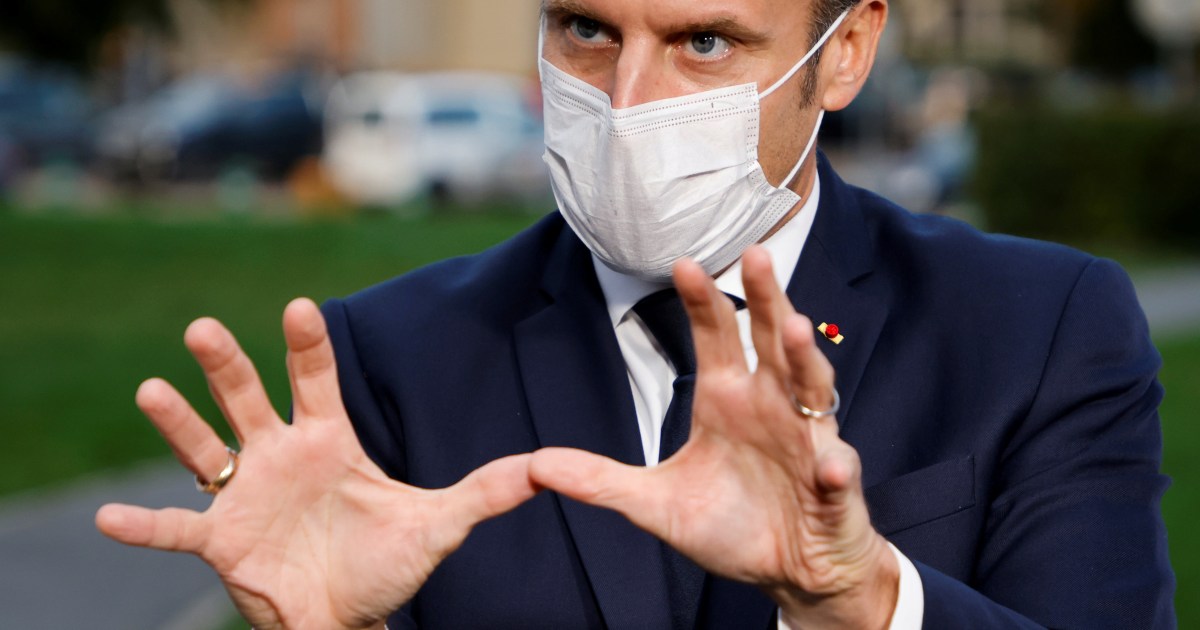

The American Washington Post said that the French response to the killing of the teacher Samuel Bate and the previous announcement by President Emmanuel Macron of a plan to fight "Islamic separatism" is a "strange" treatment of the problem whose aim is to "reform Islam" instead of eradicating the real causes. To violence.

The newspaper stated - in an article by its Paris correspondent, James McAuley, who holds a PhD in French History from Oxford University - that instead of addressing the causes of the "isolation" of French Muslims, especially in marginal neighborhoods and suburbs, which experts widely agree is the cause The main thing that makes some vulnerable to extremism and violence is that the government aims to influence the practice of a 1,400-year-old religion, whose teachings are followed by about two billion "peaceful" people around the world, tens of millions of whom live in the West.

She adds that this "strange" approach may be the only one France can think of, at a time when it cannot adhere to measuring its "systemic racism" that feeds many of the separatist tendencies that it seeks to combat.

The writer believes that France's vision of the principle of secularism approved by the law of 1905 changed, specifically in the post-World War II period, after the Muslims and their descendants came in large numbers from former colonies in North and West Africa in particular and settled inside French lands.

With these changes - the writer adds - gradually a new interpretation of secularism emerged, an interpretation that often puts the country in the face of expressions of Islam in the public sphere and has no basis in law.

McCauley asserts that after France’s humiliating defeat in Algeria in 1962, a deep wound that has not yet been largely healed, French citizens began to see general expressions of Islam (such as the veil or prayer halls and mosques) as attacks on the country's secular essence, even if the state remained Committed to respecting the holidays during major Catholic events.

The “blunt criticism” and anti-Muslim prejudice, especially by the white and right-wing French, led many French Muslims to withdraw - some of them forcibly - from the public sphere and live in the kind of "counter-society" that Macron and French politicians feared.

Explanations are extreme

The author believes that some conservative commentators in France are not wrong when they consider that some of the suburbs surrounding cities such as Paris, Lyon, and Marseille are effectively "lands lost by the republic," often a breeding ground for extremist interpretations of Islam, anti-Semitism and gang activity, which creates fertile grounds for "terrorist violence."

And he asserts that a "structural" explanation is the only way to understand why these areas are "lost" from the hands of the French Republic, as unconscious (and sometimes intentional) bias leads to the exclusion of minorities - especially Muslims - and the French press hastens to accuse them of "complicity with terrorism" on them whenever One of them dared to criticize the doctrine of the existing order.

McCauley believes that President Macron's "understandable" desire to address a real threat is not the problem. His proposed law against "Islamic separatism" may prevent extremist preachers from reaching worshipers and the spread of hate speech on social media, two factors he believed to be a stir in the killer Samuel Patty. Matters do not hide the problems of isolationism and a lack of commitment to the values of the Republic, which the French state helped to promote, intentionally sometimes and unintentionally in other cases.

The writer concludes that the emergence of this "counter-society" in France has causes, some of which are linked to Islam, but others are closely related to the French state and its policies.