Respiration as we know it is the lungs' ability to absorb oxygen-rich air in the process of inhalation, and to release air loaded with carbon dioxide out of the body in the process of exhalation.

For bacteria that do not have a lung, their breathing is more complicated than for a person. The bacteria may ingest organic waste, produce electrons, and generate a small electric current in the process.

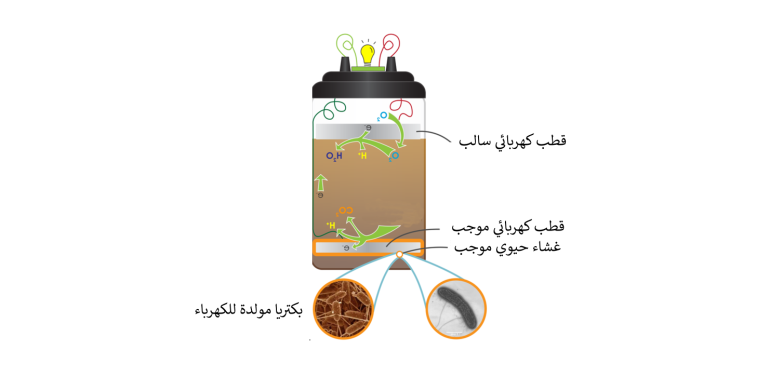

In a study published on August 17 in the journal Nature Chemical Biology, American researchers discovered how to integrate this renewable energy into a powerful microbial energy grid, and they hope to use it to generate electricity in fuel cells in the future.

Impressive bacteria

Geobacter is a type of bacteria that lives in harsh conditions inside volcanoes, deep depths in the ocean, or even inside the intestines of humans.

Geobacter cells breathe anaerobically, use the available metals as acceptors of electrons, and have capabilities that make them useful in biomedicine.

The electrons produced by these bacteria always need somewhere to go (usually an abundant mineral such as iron oxide), and geophytes have an unconventional tool to make sure they get there.

Nikhil Malvankar, associate professor at the Institute of Microbial Sciences at Yale University in Connecticut, told Live Science, "The sinuses breathe through what is essentially a giant breathing tube, hundreds of times more in size."

A breathing tube is called a nanowire, and although this conductive fine filament is 100,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair, it is able to transmit electrons at distances from hundreds of times the length of a sinusoidal cell to thousands of times.

The nanowires - which allow bacteria to breathe in the absence of oxygen - are essential to keeping cells alive, and thanks to this adaptation, pockets of bacteria are among the most impressive respirators on Earth.

The Secret Molecule

Using advanced microscopy techniques, the researchers uncovered the "secret molecule" that allows geobacter bacteria to breathe, and found that by stimulating bacterial colonies with an electric field, they can conduct electricity a thousand times more efficiently than they do in their natural environment.

The big question that angered Malvankar and his colleagues was: How could the microbes on the 100th floor of a high-rise building - as he put it - release electrons all the way to the bottom of the pile, then effectively exhale the electrons through a nanowire at a distance exceeding the body length of the original microbe thousands. Times?

Malvankar said such distances "have never been seen before" in microbial respiration, and they underscore how uniquely geobacter it is when it comes to extreme environments.

When stimulated by an electric field, peobacter creates an unknown type of nanowire made from a special protein (Pixabay).

To discover the secrets of these nanowires, the authors of the new study analyzed the colonies of gyroscopes using two advanced techniques: The first is called high-resolution atomic force microscopy, which collects detailed information about the nanowire's structure by touching its surface with a highly sensitive mechanical probe.

With a second technique called infrared spectroscopy, the researchers identified specific particles in the nanowires.

"Using these two methods, the researchers saw a unique fingerprint of each amino acid in the proteins that make up the characteristic nanowires of the geobacter," said lead researcher in the study Sebel Ebru Yalcin, a research scientist at the same institute - to the "Live Science" website.

The team found that when the bacteria are stimulated by an electric field, they produce a previously unknown type of nanowire made of a protein called OmcZ, which creates nanowires that conduct electricity up to a thousand times faster than the typical nanowires they produce. Gobacteria in soil, allowing microbes to send electrons over unprecedented distances.

"It was known that bacteria could produce electricity, but nobody knew the molecular structure ... Finally, we found this molecule," Malvankar said.

Researchers hope to use the breathing energy of bacteria to generate electricity in fuel cells (MFCJ 2010-Wikipedia)

Live batteries breathe

The researchers argue that understanding these electrical modifications could be a critical step in converting geobacter colonies into live-breathing batteries.

"We think this discovery could be used to make electronics from the bacteria under your feet," Malvankar said.

With this new research, scientists now know how to manipulate microbial nanowires to make them stronger and more conductive.

And although we're still far from charging our portable personal devices with a handful of bacteria, the strength of the newly discovered microscopic electrical grid has become a little easier to understand.

"This information could make the production of bionics both cheaper and easier," Malvankar said, "and we hope it heralds a new generation of environmentally friendly batteries that run on bacteria."