The British Social History Association today awarded its annual award for 2020 to the book "The Pursuit of Justice ... Sharia and Forensic Medicine in Modern Egypt" by Egyptian historian and academic Khaled Fahmy published by the University of California publications.

The award committee said on the association’s website that the book won admiration among powerful competitors, and praised its rich sources and its attractive depiction of historical narratives and the experiences of ordinary people.

Based on the research in the Egyptian Archive, the author - who works as Professor of Sultan Qaboos bin Said Chair for Modern Arab Studies at Cambridge University - explains how the state affected the people subject to it, and how their responses were shaped.

Fahmy provides exciting new interpretations - “neither colonial nor national” - to explain how Sharia is actually applied, how criminal justice works, and how medical scientific knowledge and practices have been activated in the modern legal system of 19th-century Egypt.

The award stated that the book focuses on the forensic (criminal) and autopsy site in modernizing Egypt, and challenges the belief that changes in this area were due to European influence, and instead the book tracks developments in the history of forensic medicine in Egyptian culture, Islamic law, and Ottoman policies, and deals with Methods by which ordinary Egyptians used medical practices to obtain justice, for example in the case of an autopsy.

To begin our online conference, we are delighted to announce that the winner of the 2020 SHS Book Prize is Prof Khaled Fahmy (@ khaledfahmy11) for the book 'In Quest of Justice: Islamic Law and Forensic Medicine in Modern Egypt' (UCP).

Read more: https: //t.co/XCboLu1Wce

- SocialHistorySociety (@socialhistsoc) June 22, 2020

Anatomy and turban

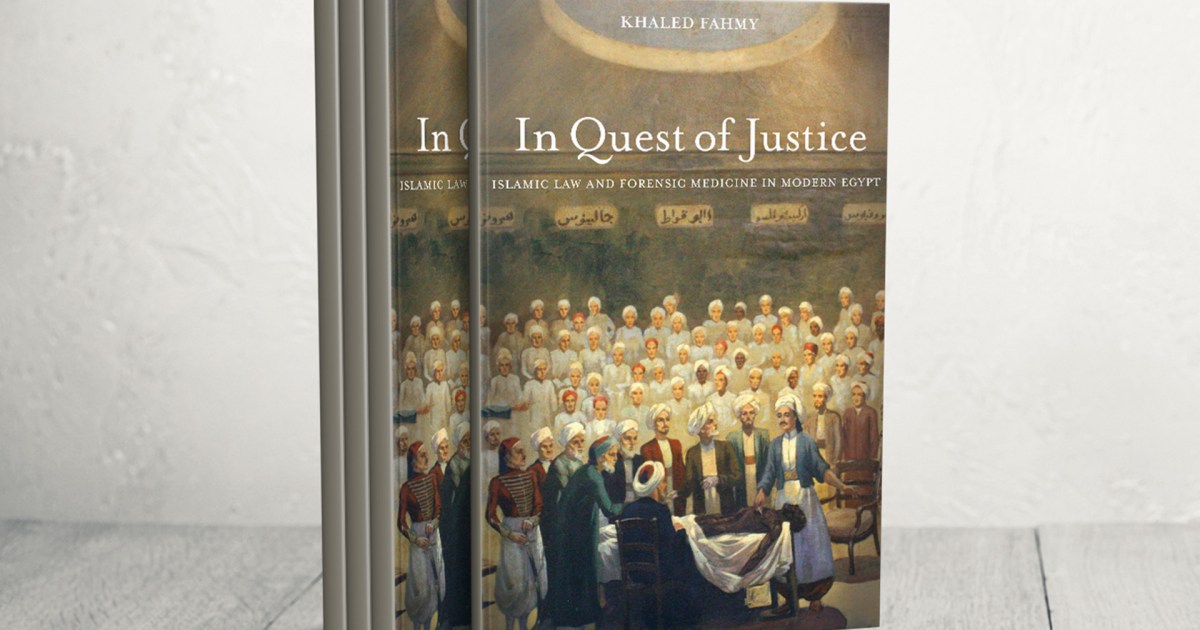

The writer begins the introduction to his book by explaining his cover, which includes a plaque preserved in a museum of medical history in Cairo showing the body of a black person on an autopsy table in the middle of a large hall whose walls adorn the Arabic names of Greek and Muslim doctors between Galen, Jabir ibn Hayyan, Hippocrates and Ibn Al-Bitar, and next to the anatomy table a doctor wearing An oriental outfit and turban, with one hand pointing to the body, apparently as an autopsy or explanation of the organs and composition of the internal human body.

Fahmy considers that the painting represents a very important event in 1829 in the Faculty of Medicine that was established at that time in Abu Zaabal, northeast of Cairo, and in the background about 100 generalized students also sit and listen attentively to the study of anatomy, in a crossing scene that brings together the professor, students, religious scholars and a military soldier , While a medical text is read by a teacher sitting on a high platform.

Fahmy reviewed in the introduction to his book the religious controversy regarding the permissibility of autopsy, and conveyed the text of a letter from the French doctor Antoine Clute (died 1868), who was entrusted by the Governor of Egypt Muhammad Ali Pasha with organizing the health management of the Egyptian army, and he became chief of army doctors, before he persuaded the governor to establish the Medical School In Abu Zaabal in 1827 to be the first modern medical school in the Arab countries.

In his memoirs, Klot Bey told Pasha (Muhammad Ali) that he wanted medical education to be based on anatomy, expressing his fear of the opinion of religious scholars who warn against touching bodies.

After he managed to calm the scientists, Clute Bey had to face the feelings of some of his hostile students, and wrote in his notes that one day a student approached him with a letter, and as soon as he began reading it until the student attacked him with a knife, he was able to avoid him, and the attacker was arrested and interrogated, so Clot was surprised Some other students sympathized with him, which was very disappointing, but this view of modern medicine at the time did not last long.

modern medicine

In his book, Fahmy not only deals with the general view of Egyptians in the 19th century for anatomy, but also traces their view of the medical school in Abu Zaabal, which was transferred in 1838 to Qasr al-Aini in the center of Cairo, where it is still today in its place on Manial Island.

Moreover, the book addresses the autopsy routinely for purposes not related to the teaching of medicine, but rather legal factors, such as verification of the cause of death, and also deals with medical practices used by the modern state that developed in the thirties of the nineteenth century to control the population of the country, such as registration At birth, vaccination against the smallpox epidemic, criminality discrimination, routine medical examination for students, workers, sailors and soldiers, health certificates when moving from one village to another, and various other examples of "physical monitoring" practices.

My understanding is that 19th century Egypt cannot be considered a colony as post-colonial studies do, and modern medicine in it should not be considered a goal to protect Europeans as is the case in European colonies in Asia and Africa.

In a chapter entitled "Forgotten Code Politics," my understanding considers that politics and jurisprudence blend and coexist side by side in 19th century Egypt, and explains how forensic (forensic) tools were introduced into the Egyptian legal system.

Intellectual competition

The book states that recent studies deny that modernization in the Middle East is linked to competition between secular and religious forces, and considers that (religious) scholars have been deeply involved in modern legal and administrative reform, focusing on the continuity of the “Sharia” and its legal system in new and different forms in the pursuit of justice. The author The relationship between medicine and law in 19th century Egypt.

In the first chapter of the book, entitled "One Medicine ... Enlightenment and Islam," the author focuses on the practice of physical anatomy, and monitors the responses of Egyptians (who are not elite) to them, as well as their view of the quarantine system.

In the second chapter, it deals with the transformations of the Egyptian Penal Code, considering that reading these changes within the context of the "bureaucratic process" is the best perspective for understanding the transition from religious (Sharia) law to "civil" law.

Unlike traditional post-colonial studies that consider the emergence of modern medicine to be associated with colonial politics, Fahmy sees that modern medicine developed in Egypt as part of the modernization movement undertaken by Muhammad Ali and his endeavor to build a strong modern army and advanced management system.

In the third chapter, "Cairo in the Time of the Khedive", the author considers that despite its independence, Egypt at the hands of Muhammad Ali Pasha (ruled between 1805-1848) remained in the Khedive era (1805-1879) an Ottoman state in terms of politics, economy and elite culture, stressing that Cairo was Class, social, and not racially divided, as is the case in the cities that were divided in colonial times between indigenous and European colonial neighborhoods.

Law on the market

In the fourth chapter, "Law in the Market ... Calculus and Sharia Chemistry", my understanding of law and Sharia is discussed, considering that the transition to civil law was not abandoning Sharia, but rather was influenced by Ottoman legal shifts that took into account political considerations alongside the jurisprudence, while stressing at the same time the effect The undeniable French in the form of modern Egyptian law.

Fahmy criticizes the view of Islamists and secularists from the left and the right for modernization in Egypt, stressing that the course of modernization in the Alawite era combined the influence of Islamic law, European legal techniques and scientific tools.

Fahmy's book complements the most famous "All the Pasha Men", in which he concludes that the Muhammad Ali Pasha Imperial project was based on building an army of Egyptian peasant recruits, while educational and industrial modernization projects were devoted to the goal of supporting the army, which would be the mainstay of the system that he would inherit for his children.

Fahmy considers that the Muhammad Ali project is understood in the broader context of Ottoman reform and modernization in the 19th century and the era of Ottoman organizations.

His book concludes with a conclusion in which he considered that the "modern Egyptian state" was not created with the aim of satisfying the needs and requirements of ordinary Egyptians, and instead tried to subject their lives to surveillance through a bureaucratic system designed to control and impose control.