A grave is not a grave until a pig is sacrificed on it, said Cicero.

In the Roman Empire, funeral rites were a matter of law, which stipulated offerings and banquets for the deceased, although not everyone (especially freedmen and slaves) could afford it.

The latest studies of the Roman necropolis of the Villa de Madrid (2nd and 3rd centuries), in the center of Barcelona, shed new light on the funerary menus of the popular classes thanks to the combination of new molecular archeology techniques with archaeozoology and traditional anthropology.

"The Romans celebrated the deceased and their passage to the afterlife with banquets and libations that were poured into the tomb, sometimes through conduits and holes that have been found in other sites.

This is a necropolis of popular classes and no rites were performed with exotic foods:

the food was the basic and cheap of everyday life, especially pork, beef and goat. We have been able to show that

ordinary people did not always comply with the law in terms of funeral parties"

, explains the biomolecular archaeologist Domingo C Salazar-García, from the University of Valencia.

In Ancient Rome,

death was quite a ceremony:

it began with the 'funeral dinner' on the day of the burial and ended on the ninth day with the 'novendial dinner', in addition to continuing to celebrate the birthday of the deceased or the cults in the festivities of the 'parentalia' (February), 'lemuria' (May) or 'rosalia' (when roses were placed on the tomb).

Although Cicero, Pliny, Petronius and other literary sources speak

of pompous meals and animal sacrifices

for the deceased (to whom their own portion of food and drink was reserved), the common people did not allow themselves great expenses.

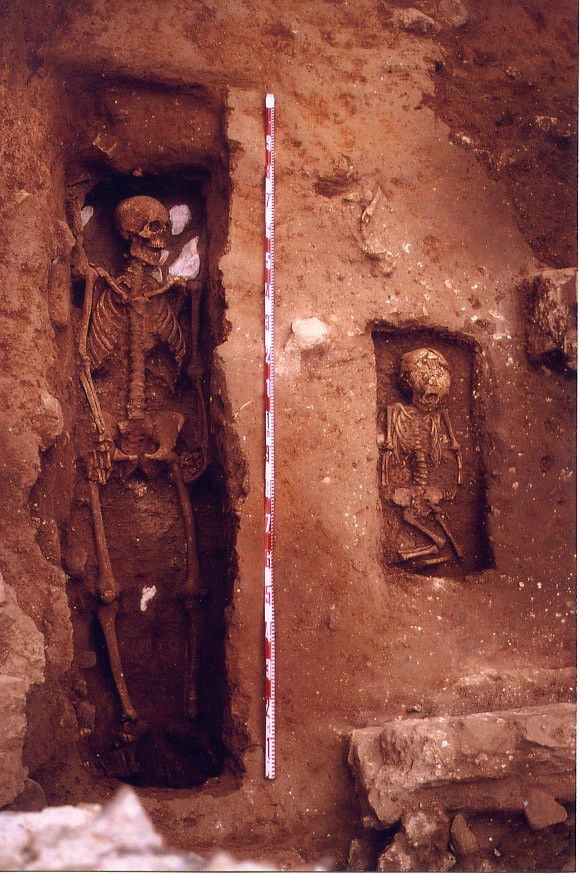

A burial from the necropolisDomingo C. Salazar-García

"It is important to study the dead to understand how they lived and to go beyond the written sources. Money is money, and whatever the importance of the afterlife in ancient Roman society, clearly living people were the priority

. micro-resistance to unreasonable rules were already present at that time"

, points out Salazar, who together with other researchers from the University of Vic and the Catalan Institute of Classical Archeology has analyzed carbon and nitrogen isotopes in animal food and human bones to find out what ate and what were the post-mortem banquets.

In funerary offerings, pigs (30%), beef (27.1%), goats (24.3%), chickens (10%), foxes (4.3%) and a testimonial presence of roe deer, rabbits, and hare (1.4% in each case).

Discovered in the 1950s, the Villa de Madrid necropolis is one of the best preserved from the imperial era in Barcino.

It is a 'funeratic college', a private association, like a mutual, in which a fee was paid to be buried.

In the excavations of the years 2000-2003,

66 burials were found

(59 burials and seven cremations), in addition to graves with horses and dogs that accompanied their owners to the afterlife.

"We also

wanted to delve into whether gender inequalities in Roman society were extrapolated to funeral rites

," says Salazar.

But, being popular classes, food consumption was lower, regardless of sex.

"Yes, two male individuals stand out with a higher protein consumption throughout their lives: because they were men? Or perhaps they came from another region, were born in the Pyrenees and died in Barcino? This is what we will study now through a analysis of the isotope of the teeth to find out where they spent their childhood," says Salazar.

The new techniques of biomolecular analysis allow obtaining hitherto unpublished information from tartar.

"Before, in archeology, tartar was discarded, it's only been 10 years since we can analyze it and find new data", highlights the archaeologist.

Conforms to The Trust Project criteria

Know more