Great report

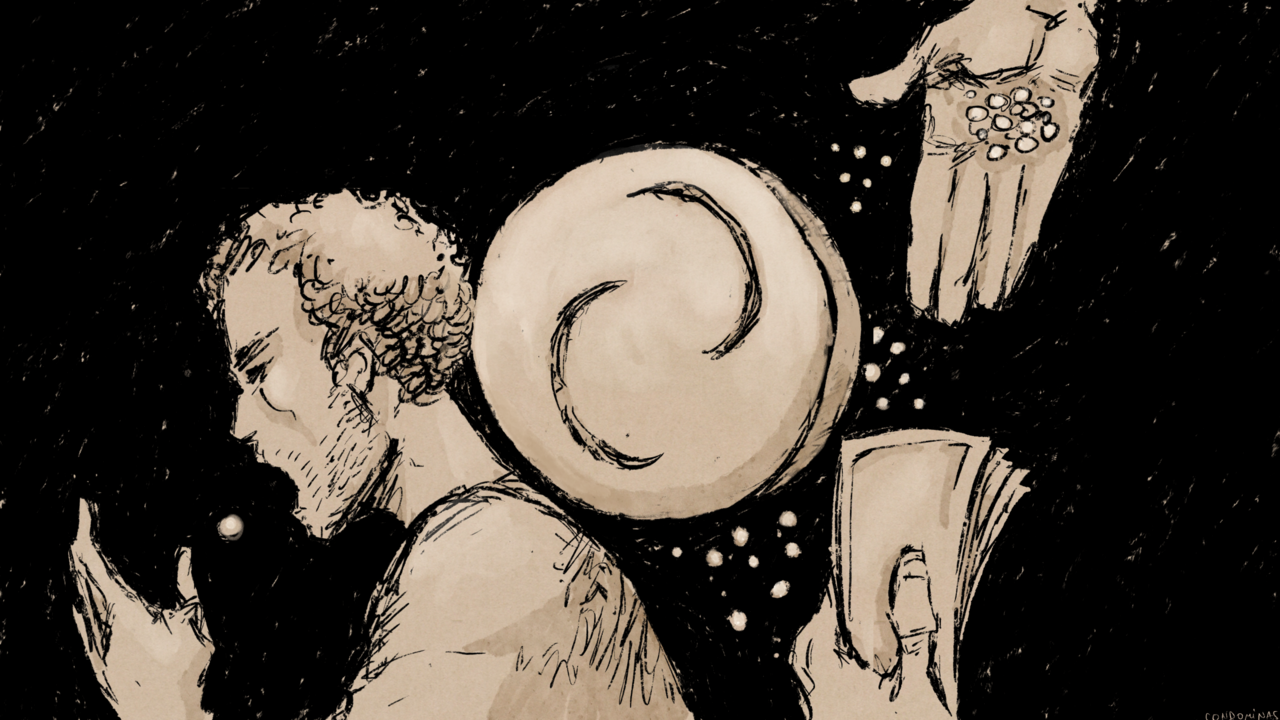

Captagon connection (1/4): two crescent moons on a tablet

Audio 7:30 p.m.

Two crescent moons on a pill.

© Baptiste Condominas / RFI

By: Nicolas Feldmann Follow |

Nicolas Keraudren Follow |

Nicolas Falez Follow

13 mins

RFI conducted an exclusive survey devoted to captagon, a drug produced and consumed in the Middle East.

Tens of millions of pills have been seized in recent years in the Gulf countries, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq.

Who uses this substance and what are its effects?

To answer these questions, Nicolas Falez, Nicolas Feldmann and Nicolas Keraudren investigated in Lebanon, Jordan and Kuwait to trace the captagon trail.

Advertising

Two crescent moons.

The pattern engraved on the pill in the palm of Abed's hand is intriguing to say the least.

"

Here's some captagon, it's a stimulant,

" explains this young Jordanian of 30 who looks ten years older.

If you take one, you won't sleep for twenty-four hours.

It will give you energy, you will feel strong, you will feel very very good.

This pill is called

"hilalein".

It

means: "the two crescent moons".

»

But as poetic as the formula is, it is nevertheless “

a kind of brand, of promotion

”, continues Abed.

He points to a cup of coffee on the coffee table in front of him, on which is written “

al ameed

”.

“

We know it's good coffee.

Well, it's the same with the

"hilalein"

pill .

It is known, we know what it is, we can identify it.

»

Shorts and a sleeveless t-shirt, Abed is sweating profusely despite the fan spinning in the living room of his family home on the outskirts of Amman.

This former consumer details the multiple types of captagon found on the market.

“

You also have the Lexus or the Mercedes.

And there is also one called "Mohammed bin Salman"

, he lists

.

The one called "ben Salman" is the strongest.

Maybe because it's the one they send directly to Saudi Arabia.

It is therefore rarer, anyone can not get it.

Despite their variety, all the pills cost roughly the same price, Abed says: between one and two Jordanian dinars [1 Jordanian dinar = 1.35 euros].

Some pills are white like sugar, some are yellow, some the color of desert sand.

It depends.

"

Doses, always more doses

"

If Abed started using it, it was "

because of bad company

", he recalls.

“

A friend offered me a pill.

It made me very active, very effective in my work.

It leaves you up at night, you have conversation.

So Abed starts by taking one pill a day.

Then, little by little, he dives: “

I wanted to have more sensations.

So I increased the doses.

From one pill a day, I went to two, then three, four, five... Doses, always more doses.

»

For this former truck driver, the captagon was such a good way to fight fatigue.

Until a certain point.

“

You're on the road driving, you feel good, but after a while, the effect suddenly disappears.

And then you can fall asleep like that, it's very dangerous.

“A year ago, he decided to stop, “

because it's not good at all

,” he admits.

“

It destroys you, it destroys your kidneys, it ravages them… It also destroys your face, your skin, your whole body.

The more tablets you take, the more stressed you will be.

Give it a try, just take it for a month or two and you will see the results.

It takes your appetite, it wears you out.

»

Captagon users describe a feeling of energy and power, but also long-term stress and fear.

© Baptiste Condominas / RFI

However, it is not so easy to obtain it in Jordan, underlines Abed.

Deals are not made in the street, but through networks of relationships.

Since possession of drugs is punishable by imprisonment, dealers play it safe.

And you usually have to go through acquaintances.

“

You have to go see a drug dealer with someone he already knows.

And it is only afterwards, once you have his confidence, that you can come and order some yourself.

»

Precautionary measures confirmed by Mahmoud*, involved in captagon trafficking for five years.

First a consumer, this thirty-year-old with square glasses and a well-trimmed beard explains that he started dealing when he saw consumption around him explode in Amman.

“

With friends, we quickly realized that we could make a lot of money, so we decided to get into trafficking.

At first it was just a few dozen pills, but over time his business only grew.

One thousand pills for 1,000 Jordanian dinars

Mahmoud nevertheless denies being one of the "

big dealers

", who buy "

pills by the millions

".

Its stocks are more modest.

Generally, he orders two packets of 1,000 pills each from his supplier, at the rate of 1,000 Jordanian dinars per packet (about 1,300 euros).

He then resells the pill at three times the price (3 Jordanian dinars, almost 4 euros each) to other dealers, who then sell them.

Sitting in the back of the car that came to pick him up in the Swaileh district, Mahmoud feverishly climbs the chain of which he is only a simple link.

A chain that starts in Syria, where "

concentrates,

according to him,

the majority of laboratories

" of captagon.

The drug then arrives at Mafraq, about ten kilometers from the border, where “

a large part of the production passes through

”.

From there, the goods are transported to Amman by transporters “

who know how to avoid checks, the police, take the back roads

”.

Mahmoud, however, assures that he is "

never in direct contact

" with the person transporting the cargo.

“

I don't know where he left or when.

It is only once he is there, in Amman, that I am contacted to find him

.

»

Dealer in Amman, Mahmoud (whose name has been changed) is considering stopping a lucrative trade.

© Baptiste Condominas / RFI

But despite a business that is rolling, Mahmoud thinks of stopping his activity.

Too much pressure at first, as evidenced by his trembling hands and his furtive glances at the front and the back of the vehicle.

“

I'm afraid of being the next arrested,

he admits.

It happened last month to a guy I know, he was arrested on the way to a supplier on the road.

A heavy fine, several years in prison... Mahmoud wonders today if the game is still worth the candle.

Especially since he achieved his goal: “

I had set myself the goal of raising 40,000

Jordanian dinars

[more than 52,000 euros]

, I achieved it, I will be able to stop.

»

And then there is also the weight of remorse.

"

I feel guilty today, I feel like I'm destroying people's health

," he says.

He recognizes the temptation of easy money in a country where there is “

not enough work with good wages

” and a society in which “

he does not find himself

”.

But he promises that he will soon stop dealing.

"

I'm giving myself another month or two

," he says in an uncertain voice.

Mahmoud's trade is a small trade on the captagon route, usually produced in Syria and huge quantities of which are illegally exported to the Gulf countries, today the main consumers of this drug.

A drug that came to turn Mohammed's life upside down.

Although Lebanese, he was born and raised in one of these countries whose name he asks not to be mentioned.

His family still lives there, but he ended up being expelled because of his consumption of captagon.

A "

very beautiful feeling

"

This 30-year-old with the face of a tired child says he started taking it when he was at school, around 15-16 years old.

He remembers “

a very beautiful feeling

” which gave him strength, energy, a feeling of superiority and control.

At the beginning only.

Because he also describes, in the long term, much less pleasant effects: fear, paranoia, insecurity... "

I doubted myself, everyone around me, I doubted my parents, I doubted everyone.

He is then "

forced to consume other products to balance

" these "

up

" moments and these "

down

" moments.

Mohammed then mixes hashish, rivotril, alcohol and heroin...

This dizzying gear is not without consequences.

In the Gulf country where he was then living, Mohammed was arrested a first, a second, then a third time.

"

I was told: 'You are under surveillance.'

Until the day when I was caught in a place, they searched me and did a blood test.

They found a lot of stuff on me and in my blood.

After a period in prison, then a forced return to Lebanon, Mohammed continued to take drugs, before starting a cure a few months ago.

He now resides in a detoxification center in Maysra, a locality in Mount Lebanon, north of Beirut.

The decor is heavenly, between the calm of the mountains, the song of the birds, and in the distance the blue of the Mediterranean Sea.

Here, everything seems serene but it should not be trusted, because the residents of the place have had painful journeys.

Damaged lives, like Mohammed's.

“

If I had known, I might not have used it

,” he confides.

But he was trapped by this “

very beautiful feeling

”.

A feeling that may explain the success of captagon in the Gulf monarchies, where it is widespread and of superior quality, confirms Mohammed.

Because for him, “

people suffer from a great void

” in these countries.

“

They don't work, they get their salaries from the state.

So everything that is forbidden, drugs, they want to try it… Alcoholic beverages don't exist, so they turn to drugs.

»

Captagon is very common in the Gulf monarchies, especially among young people.

© Baptiste Condominas / RFI

boredom and frustration

An analysis shared by the professor of sociology in the department of social sciences at Kuwait University, Ali Altarah.

According to this former senior official of the administration, young Kuwaitis fall into drugs due in particular to the lack of entertainment in the country.

“

What can they do?

Other than driving around the streets.

Flirting, seeing girls... They don't have any activities.

And they cannot compensate by turning to alcohol, the consumption of which is prohibited, as in Saudi Arabia.

But the professor also believes that it is “

a matter of frustration

”.

He thinks that “

young people get lost, they don't know what they want in life

” and that they don't find their place in a society that excludes them from decision-making processes.

Young people are isolated and not part of society's development plans.

These kinds of factors can therefore increase the likelihood that young people will turn to drugs.

A specialist in youth, Ali Altarah closely followed the appearance of captagon in Kuwait, a small emirate of less than 5 million inhabitants located on the borders of the Gulf.

He points out that this is not a recent phenomenon but that it has increased in recent years, becoming a “

serious problem

”.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shed particular light on the subject, he explains.

During the curfew, young people had to stay at home and could no longer obtain captagon.

The lack then provoked extreme reactions.

“

Suddenly, the families realized that their children were violent.

The police were coming and that's when they found out that the number of Kuwaitis involved in drugs is very large.

In both boys and girls.

»

devastating effects

Violent behaviors are not the only consequences of withdrawal.

Amine Benyamina, head of the addictology and psychiatry department at the Paul-Brousse hospital in Paris, recalls that captagon, as an amphetamine, stimulates vigilance, the fight against fatigue, intellectual performance and "

excites everyone basal metabolism, especially the brain

”.

But when consumption stops, the effects are devastating: great fatigue, difficulty in sleeping and even the risk of convulsions and cardiac arrest.

The specialist in addictology compares this to “

an engine in which you put kerosene, a super powerful fuel

;

when you stop, the engine falters

”.

It is neither more nor less than “

a crash phenomenon

”

,

explains Amine Benyamina.

Phenomenon regularly observed

in users of amphetamines or psychostimulants.

“

All the targets through which this product passes risk ultimately going beyond their capacities and decompensating

”, summarizes the doctor.

If captagon stimulates vigilance, the fight against fatigue and performance, experts warn of the consequences on the psyche and the body, such as exhaustion, sleep problems, risk of cardiac arrest.

© Baptiste Condominas / RFI

But before being a dangerous drug, captagon was "

a legal drug based on fenetylline

", a substance from the amphetamine family, recalls Laurent Laniel, analyst at the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction, an agency of the European Union based in Lisbon, Portugal.

This drug was banned in the 1980s and stocks of fenetylline – its active ingredient – have been largely destroyed.

Today, the captagon pills circulating in the Middle East "

no longer have anything to do with the drug

", insists the researcher, in particular because they contain amphetamine sulphate, which is more powerful than fenetylline.

Laurent Laniel also warns that the composition of the captagon could change over time.

"

It is always possible that the ingredients used to make the pill will change in the future

," he warns.

Amphetamine could, for example, be replaced by methamphetamine, a devastating synthetic drug.

But whatever its future, today's captagon already has very real consequences on the youth and societies of the Middle East and, beyond that, on relations between States in the region, at the heart of a complex and sprawling traffic.

Editing and drawings: Baptiste Condominas

Newsletter

Receive all the international news directly in your mailbox

I subscribe

Follow all the international news by downloading the RFI application

google-play-badge_EN

Geopolitics of drugs

Dope

Jordan

Syria

Lebanon

Kuwait

Saudi Arabia

United Arab Emirates

captagon login