Obituary The soldier who kept fighting 30 years after the surrender of Japan dies

"Where was the present?

Every inch his foot advanced was something to come, every inch behind him was a thing of the past... We think we live in the present, but the present cannot exist.

Am I, am I alive, am I at war?

But what about all the times he walked backwards to confuse the enemy?

The steps taken backwards also went towards the future».

The text is from

Twilight of the World

(Blakie Books), the recently published novel (first novel) by film director Werner Herzog.

The paragraph about timeless time is reflected like in a mirror in

Onoda.

10,000 Nights in the Jungle

, the film by Frenchman

Arthur Harari

just released.

The two, novel and film, talk about the same thing.

And it would seem that they do it in the same way between fascination and simple terror;

between admiration and astonishment.

“He was required to sacrifice himself, but without dying.

Ritual suicide or seppuku

was expressly prohibited

.

He had to resist.

His entire history lives in the paradox of respecting a code of honor that is nothing more than a very elaborate form of cowardice.

.

It is a story that contradicts the myth of the kamikaze », explains Harari via zoom to also explain to himself his own dazzlement by the character of Hiroo Onoda.

To situate us, his film, which surprised at the last Cannes Film Festival for its unprecedented, profound and desperate nature, focuses on one of the most surprising stories (admirable and also mythical) that any war has given: that of the soldier unable to give up.

Onoda's is the story of a soldier who in 1945, at the end of World War II, was ordered to resist on the Philippine island of Lubang.

There he withdrew with three other men to the bottom of the jungle and there he waged a guerrilla war against his own ghosts and against the local population awaiting the Japanese imperial army that lingered.

And it was delayed.

In 1974, almost three decades after the capitulation, a student named Suzuki found him.

I was looking for him and a panda bear and the Yeti.

And, the hardest part, he convinced her to give up what had been a detained life.

And without time.

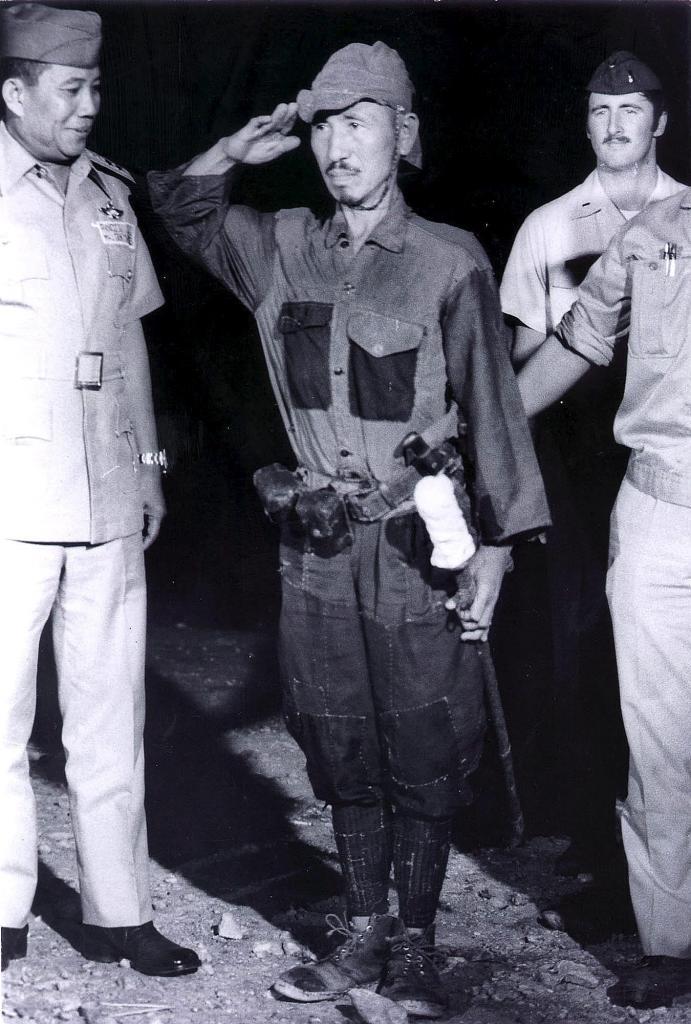

Japanese imperial soldier Onoda salutes at the moment of his surrender on the Philippine island of Lubang, after holding out in the jungle for 29 years, despite Japan's 1945 surrender in World War II.AP

The story is by no means new.

Not even little known.

In fact, Onoda soon acquired the category of a symbol, a pop myth and a standard for both those who made him an example of pride, sobriety and fidelity to a mission, to a given word, as well as those who made him a danger and a sign. evident fanaticism, victim of a ruthless military education and flag of a poisoned nationalism and

denial of the atrocities of colonialism.

Herzog himself (more on the side of the former than of the latter, and always aware of the non-stop rage of how many characters like Aguirre have caused madness) tells at the beginning of his book that in 1997, when he was in Japan on the occasion of his work directing the opera

Chushingura

, exchanged the formal offer of meeting the emperor himself for that of meeting Onoda.

Onoda would die at the age of 91 in 2014.

Harari acknowledges that he came across the story almost by chance.

“I was looking for a classic adventure story about survival in extreme conditions.

So, my father told me about Onoda.

And I was quickly captivated by his vagueness.

It is an action story, an adventure story, but in reality, nothing happens.

There is no purpose.

The argument is that of war films, but everything is too abstract.

The protagonist is a hero, but his greatest feat was to kill some poor peasants in peacetime [the pardon received by the Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos was always much discussed]", he explains determined to find the best non-definition of what , he asserts, has no possible definition.

The film, in fair correspondence,

she remains for the three hours that it lasts in a state of almost hypnosis, always determined to capture the exact moment in which the present loses its footing.

"Each step taken was the past and each step to be taken was the future," writes Herzog in what could be considered an unconscious reading (or

avant la lettre

)

of Harari's prodigious work

that equally endorses the more angry

John Ford

than the more mystical

Kenji Mizoguchi.

For the director, and without rushing the parallels, something remains of the Onoda war that represents us.

And he even defines us.

And he has nothing to do with elaborate philosophical arguments rooted in humanism, which too, but with the perverse mechanism of any war.

Including ours now in the Ukraine.

«

Onoda was able to interpret any signal that occurred around him as a confirmation of his mistake.

The troop movements for the wars in Korea or later Vietnam were nothing more than evidence for him that everything was still the same, that he had to resist.

The sad locals' response to his desperate harassment became the driving force behind his delusion.

How can we not think that this blocking of information does not correspond to what we are experiencing now?

Does the idea of the Russian people about the invasion of Ukraine have anything to do with what we have? », He wonders.

Herzog says that "the jungle does not recognize time."

And Harari maintains that the experience of time is basically the essence of cinema.

It is clear.

Conforms to The Trust Project criteria

Know more

Ukraine

Japan

cinema