The year is 1971, in a suburb of Chicago, Free Church pastor Hildebrandt lives with his wife and four children.

The church has a youth group, Crossroads - Crossroads - led by a charismatic and long-haired young preacher who is taken from the musical Jesus Christ Superstar.

In the group, three of the children Hildebrandt are active, they do not devote much time to religion as to social experiments, the members learn to be honest with each other and take responsibility.

The pastor is hurt that the children joined the group because he himself had to leave it after the collective voted him out of the community, for good reasons it should turn out.

Pastor Hildebrandt is in crisis

and it will soon be clear that his family is falling apart.

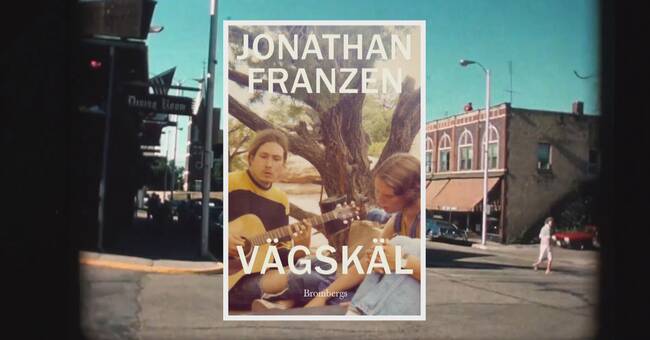

Crossroads is a large 640-page story, the first part of a planned trilogy and, as always with Franzen, a novel that takes the tempo of society, plots its undercurrents and wants to reveal the world as it really is.

In 1971, the Vietnam War took place, the image of the United States as a world-improver crackled, but in the Hildebrandt family, the dream of the right and good is still unchallenged.

The omniscient narrator

in the novel gives all members of the family except at least their own chapters, where above all their inner life, their efforts to be true and do good, are cut and tested against reality.

The family, like society as a whole, is exposed to forces that threaten cohesion: father in the house desires another woman, middle son desires only drugs, only daughter falls in love and sees God, eldest son wants to go to Vietnam to not be better than all the black young men who do not get a reprieve for studies, and mother in the house carries a secret.

Franzen's success in keeping the interest in all the different stories alive is partly due to the fact that he is really curious about his characters, their anguish and their longing, and partly because he manages to portray their small world so that it never obscures the big world.

To take just one example

of the novel's many double exposures: The pastor visited a Navajo reserve in his youth, went there alone, stayed for several months and made, as he believes, friends for life.

Now he goes there with the young people in Crossroads, he has been resumed in the group, but his efforts for the Navajo people fall like barren grain on the rock: it is another time, his motives for the journey are purely selfish and are no longer about humble striving to understand and assist the stranger.

The pastor, like his country, takes the colonization of the indigenous people for granted.

The United States' efforts in the world are not mentioned in this context, but the parallel is obvious, perhaps too transparent, but I never have time to be really thoughtful before the story goes on a new track and pulls me along.