For 10 years, negotiations on the Renaissance Dam, which Ethiopia built on the Blue Nile, continued sporadic and accompanied by controversy and disagreements, until it turned into one of the most prominent crises regarding the sharing of water resources in the world.

The three countries - Ethiopia (the upstream country), Sudan (the transit country) and Egypt (the downstream country) - did not reach an agreement on the filling and operation process.

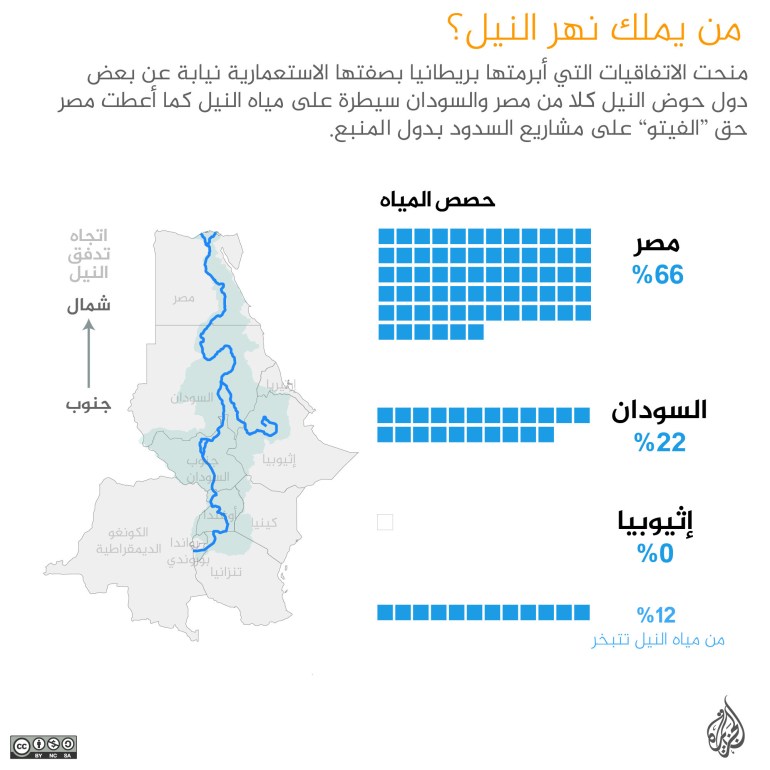

The historical differences and interpretations related to previous agreements and the quotas that were approved by them, especially the 1902 and 1959 agreements, which Ethiopia considers unfair to it, are present in the crisis.

Ethiopia is preparing to start the second phase of filling the giant dam with the start of the rainy season at the beginning of next July, amid Egyptian and Sudanese accusations of trying to impose a fait accompli and completing the dam on its terms, which will have profound negative effects on the two countries economically and socially at the medium and long levels, and will lead to Retreat their historical share of river water.

This comprehensive interactive coverage presents the dimensions of the dam crisis in its political and economic aspects and its developments, and monitors the effects of the dam on Ethiopia and Sudan, and on Egypt in particular (as it is the most affected as a downstream country), according to a scientific analysis that deals with assumed filling scenarios, and is also concerned with shifts in attitudes and scenarios for resolving the crisis.

The following chronology shows the agreements made between the Nile Basin countries since the beginning of the last century.

The Renaissance Dam... An Ethiopian dream that haunts Egypt and Sudan

Who owns the Nile

Ethiopia began building the Renaissance Dam in April 2011 on the Blue Nile in the Benishangul-Gumuz state, near the Ethiopian-Sudanese border, 980 km from the capital, Addis Ababa.

It is a double dam consisting of a concrete main dam that is erected at a height of 155 meters, and stores about 14 billion cubic meters of water.

As for the dam, “Al-Sarg” dam built of rubble and a concrete layer half a meter thick, 4800 meters long and 55 meters high, it is a reserve (complementary) dam that stores about 60 billion cubic meters of water, and allows any excess water to be drained from the dam’s main reservoir to the main course of the Nile .

On November 13, 2019, Ethiopia announced the completion of the construction of this part, while the main dam is expected to be completed in early 2023.

The following infographic provides basic information about the Renaissance Dam and its ability to produce electricity compared to the High Dam in Egypt.

(The island)

What does Ethiopia want?

Ethiopia claims what it calls geographical rights, considering that about 80% of the waters of the Nile originate from its lands.

It rejects the terms of the 1929 and 1959 agreements on sharing the Nile waters, especially the prior Egyptian approval of irrigation projects in upstream countries.

Addis Ababa insists that the period of filling the dam lake be within 7 years at the latest, and that storage continue throughout the months of the year, and believes that the 40 billion cubic meters of water required by Egypt annually will hinder its ability to fill the dam on time and produce electricity.

Ethiopia also rejects the presence of Egyptian experts during the process of filling the dam, or the joint management of it, as well as placing other openings in the dam.

An image showing the dimensions of the water reservoir that formed behind the Renaissance Dam (Al-Jazeera)

Ethiopia rejected the Egyptian-Sudanese initiative to form an international quartet to lead negotiations on the Renaissance Dam, and stressed that it would deal only with the African mediation represented by the African Union.

It also refuses to abide by any agreement restricting its right to complete the filling process.

Despite the doubts of some experts about its feasibility, especially on this scale, Ethiopia is counting on the Renaissance Dam to meet its growing energy needs and achieve a comprehensive development renaissance.

And it plans to become the largest energy exporter in Africa, and to sell about two thousand megawatts of surplus electricity to neighboring countries.

The Ethiopian authorities assert that the dam will contribute to the development of major agricultural projects and fishing activities, the development of the local economy, the promotion of a new commercial network near the region, the provision of job opportunities, and the increase and diversification of food provision for the local population.

The following infographic highlights the extent to which Ethiopia is currently dependent on hydroelectric energy without other energy sources, compared to the general average in the African continent.

Ethiopia has actually started filling the dam’s reservoir, as it completed the first phase in July 2020, and pumped nearly 5 billion cubic meters of water, despite reaching an understanding with Egypt and Sudan to continue negotiating the filling and operating rules, and Ethiopian officials attributed this mainly to Rainfall.

Sudan, the meeting point of the Niles

The meeting of the two Niles in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum (social networking sites)

In the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, the White Nile - coming from Lake Victoria, located on the borders of 3 countries, Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya - meets the Blue Nile coming from Lake Tana in Ethiopia, and the Nile has left its mark on the capital of Sudan, where it originated on its banks of its three components: Khartoum, Khartoum Bahri, Omdurman;

I knew the triangle capital.

From Khartoum, the Nile continues its way north for 2,500 km, ending up in the Mediterranean Sea.

What does Sudan want?

Sudan requests Ethiopia to abide by the agreements on shared international waters, including prior notification of the construction of any dam on shared rivers, which guarantees the water rights of the countries concerned.

Khartoum, through the mediation of the Quartet (the United Nations, the European Union, the African Union, and the United States) before the completion of the second filling process, demands that Addis Ababa sign a legally binding agreement, not just general guidelines on the amount of water retained and the timetable for filling, and that it spells out precisely how to resolve future disputes.

Roseires Dam reservoir in Blue Nile State (Al Jazeera)

Sudanese experts believe that the construction of the Renaissance Dam will achieve several benefits for their country, the most important of which is regulating the flow of the Blue Nile throughout the year, and thus the multiplicity of agricultural cycles and the prevention of devastating floods, as well as the dam’s seizure of large quantities of silt and tree trunks that were causing the turbines to close two main reservoirs in the east of the country.

On the other hand, other experts believe that the significant reduction in the quantities of silt will lead to the impoverishment of the fertile soil, and thus the inability of Sudan to achieve its old strategy of achieving food security for itself and becoming the food basket of the world. They also believe that the country’s share of water will be affected if the damages resulting from the dam are shared with Egypt. .

The Sudanese expert in international law, Dr. Ahmed Al-Mufti, believes that the Renaissance Dam threatens the Sudanese with drowning and thirst, in the absence of an agreement that guarantees the safety of the dam, water security, and compensation for economic, environmental and social damages.

According to him, the first filling of the dam, which took place between June and July 2020, was reflected in the water discharges of the Roseires dam.

These discharges decreased to 124 million cubic meters, compared to 448 million cubic meters previously, and the discharges of Sennar Dam also decreased to 73 million cubic meters, compared to 373 million cubic meters previously, and the level of the Nile waters in Khartoum also decreased.

The first filling of the dam also affected the Nile drinking water stations in the capital, Khartoum, such as Al-Saliha and Soba.

A souvenir photo of officers from the Egyptian and Sudanese armies prior to the start of the Hamat al-Nil exercises (social networking sites)

Sudanese position shifts

The Sudanese position on the Renaissance Dam until mid-2020 remained “neutral” between Egypt and Ethiopia, and mostly political and media positions focused on the positive repercussions of the dam on the Sudanese economy, and its role in regulating the flow of the Nile throughout the year and preventing floods, and thus the multiplicity of agricultural cycles, providing Cheap electricity and maintenance of electricity-generating dams.

Also, some voices believe that the 1959 agreement is an unjust agreement for Sudan and the Nile Basin countries, and that Khartoum made concessions during it, which is almost the same as the Ethiopian position on the agreement.

But recent months have witnessed a shift in Khartoum's position, as it moved closer to the Egyptian position in the direction of pushing to sign a binding agreement with Ethiopia before filling the dam.

There have been voices questioning the structure of the construction of the dam itself and its dangers to Sudan, stressing that the decline in the level of the Nile water flowing into Sudan may affect it more than Egypt, given that the latter has a huge reserve around the Aswan Dam.

In this regard, it can be noted the position of the Sudanese Minister of Water Resources, Yasser Abbas, who spoke in February 2020 about the advantages of the dam in terms of ensuring cheaper electricity, a stable agricultural season and regulating the flow of the Nile, to return at the beginning of 2021 to talk about the dam’s threat to the national security of Sudan and the environment In addition, the head of the Sudanese Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, spoke in April 2020 about the need to sign a binding written agreement regarding filling.

The Sudanese Minister of Foreign Affairs, Maryam Al-Sadiq Al-Mahdi, stated in early June 2021 that the second filling of the dam without a legal agreement represents a real danger to Sudan.

She also indicated that the Ethiopian "intransigence" may drag the region into "unfortunate pitfalls."

Al-Burhan (right) and Sisi meeting amid a Sudanese-Egyptian rapprochement regarding the Renaissance Dam crisis (Reuters)

In addition to what Khartoum saw as Ethiopia's "intransigence", it was not only related to the issue of filling and operating the dam, but also to controlling the water;

This transformation is mainly due to political reasons and to the differences that existed between Egypt and Sudan during the era of President Omar al-Bashir and at the beginning of the revolution when the Transitional Council ruled, as the position on the dam and approaching Ethiopia in the crisis was considered one of the pressure cards on Cairo.

Ethiopia, in turn, sought to get closer to the new authorities in Sudan, and played the role of mediator between the opposition "Forces of Declaration of Freedom and Change" and the Transitional Military Council, hence the visit of its Prime Minister Abi Ahmed to Khartoum on June 7, 2019 as a mediator of the African Union, and then on August 25 August 2020 on an official visit, which followed a similar visit by an Egyptian delegation to the Sudanese capital.

Conflicts between civilians and the army imposed themselves within the Transitional Council, where the military leaders of the Council tended to develop relations with Cairo, so the position on the dam became close, and Khartoum, for example, rejected Ethiopia’s proposal to sign a bilateral agreement for the first filling of the dam and adhered to the tripartite agreement (open the link to read the terms of the Agreement of Principles on the Dam Renaissance).

The growing tension between Sudan and Ethiopia over the border area of Al-Fashqa played its role in changing the Sudanese position on the dam, as one of the pressure cards on Addis Ababa, and Khartoum hosted joint maneuvers with the Egyptian army under the name “Nile Eagles” and then “Nile Guardians”, which Ethiopia considered A bilateral message related to the Renaissance Dam before the border crisis.

The Ethiopian-Sudanese tension over the Al-Fashqa area contributed to changing Khartoum's position on the issue of the Renaissance Dam (Al-Jazeera)

Egypt .. Will the gift of the Nile remain?

With the start of the operation of the Renaissance Dam, Egypt fears a threat to its water share of 55.5 billion cubic meters of water, and seeks to maintain an acceptable level of Nile water flow during and after the years of filling the dam’s reservoir.

Cairo also fears the destruction of large areas of agricultural land, the drop in the groundwater level, the intrusion of sea water in the Nile Delta, the increase in salinity in its lands, the increase in pollution and the threat to farms and fisheries.

As well as the energy and health sectors were negatively affected by this water crisis.

Water desalination requires large amounts of energy, and the water deficit causes water pollution and with it the spread of several diseases such as hepatitis, which still affects millions of Egyptians.

To bypass these problems, Egypt wants to fill the Renaissance Dam in a period of 10 to 21 years, taking into account the drought years.

Egypt refuses to reduce its share of water from 40 billion cubic meters annually, and insists that water storage behind the dam is limited to the rainy season only, and that storage stops in times of drought.

Cairo also requires increasing the number of water passage holes inside the dam from two to four, to ensure the continued flow of water during periods of weak levels of the Nile.

During the rounds of negotiations in recent months, Egypt insisted that Ethiopia sign a "balanced, binding and fair agreement" regarding the filling and operation of the dam, and that negotiations take place according to a specific timetable under the auspices of the United Nations, the European Union, the United States and the African Union.

It also requested the intervention of the Security Council to put pressure on Addis Ababa.

Egypt relies heavily on the waters of the Nile River for agriculture, but in return it relies on fossil fuels to a large extent compared to hydroelectric power despite the presence of the High Dam, as the following graph highlights.

The Delta..the food basket under threat

The delta in northern Egypt was formed over time in the form of a triangle, as a result of the accumulation of silt brought by the Nile and its branches into two branches before reaching the Mediterranean;

The Damietta branch in the east ends in Damietta, and the Rashid branch in the west ends in the city of Rashid.

The delta is 161 km long from south to north, and extends on the Mediterranean coast with a length of 241 km from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the east. It is among the largest in the world, and is inhabited by more than 40 million people.

The delta is famous for the fertility of its arable soil throughout the seasons due to the abundance of water and moderate sunny weather throughout the year.

The coasts of the delta have been suffering from the acceleration of seawater ingress and its impact on the fertility of the lands since the construction of the High Dam in 1969 due to the retention of a large proportion of fertile natural sediments behind it and its failure to reach the estuary to equalize the erosion of the beaches.

With the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and the decreasing water flow towards Egypt according to the years of filling the reservoir, the delta will become the largest threatened area within the Nile Basin because of the radical changes that a drop in flow rates in its two branches can cause.

Ethiopia announced that it had pumped 4.9 billion cubic meters of water into the dam's reservoir (social networking sites)

Filling years and crisis scenarios

Dr. Essam Heggy, a space scientist who specializes in studying water on Earth and in the solar system, shows the risks facing the delta and agricultural lands on the banks of the Nile, according to the scenarios related to the filling period of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam reservoir, which ranges between 3 and 21 years.

Although Ethiopia actually completed the first stage of filling and pumped about 5 billion cubic meters of water into the dam’s reservoir in July 2020, and intends to complete the second stage by pumping about 13.5 billion cubic meters, in light of the Egyptian-Sudanese rejection and stalled negotiations;

All scenarios are still possible.

This presentation is based on scientific research published during the last ten years in references and refereed scientific studies.

The scenario of short filling of the Renaissance Dam (3 years) may lead to an average water deficit of approximately 31 billion cubic meters annually - an estimated 40% of Egypt's current water budget - and thus reduce the current agricultural area by 72%.

This will result in a drop in agricultural GDP from $91 billion to about $40 billion during the filling period.

This will also result in a decrease in per capita GDP by 8% and an increase in unemployment rates by about 11% over the current rates.

Scenarios

What are the Egyptian alternatives?

As a result of Egypt's complete dependence on the waters of the Nile River, it is the only downstream country that is affected by the serious repercussions due to the change in the flow of water in the river after the start of the filling phase of the Renaissance Dam reservoir.

Most of the initial estimates indicate that the Renaissance Dam will cause a deficit that Egypt cannot compensate using the available means, and there will remain an average deficit of 10 billion cubic meters per year (equivalent to one-sixth of Egypt’s water share) under the most likely scenarios of the process of filling the Renaissance Dam, which is a scenario The seven years.

If we add this potential deficit (10 billion m3) to the current deficit of 18 billion cubic meters per year, the water deficit will reach nearly half of Egypt's water budget.

The following infographic shows the possible alternatives for Egypt to fill the shortage of Nile water, and the extent of the ability to achieve this by calculating the size of the expected water deficit.

Stalled negotiations .. How will the crisis be resolved?

The Kinshasa negotiations round (the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo) did not produce any progress to resolve the crisis, as Ethiopia refused to form a quartet committee to approve a schedule of discussions to resolve the contentious issues before the start of the second filling of the dam.

This coincides with Egyptian military and diplomatic movements with countries neighboring Ethiopia (Sudan, Kenya, Djibouti, Burundi and Uganda).

Amid unofficial talk in Egypt about the possibility of a military option to strike the dam, there were simultaneous Western warnings against any military action, as the United States and the European Union called for a consensual political solution between Cairo, Khartoum and Addis Ababa, through negotiations sponsored by the African Union.

And if Ethiopia implements the second filling in the coming days or weeks, the time for a political solution will become more difficult, and the military option by Egypt will be too late, given that the dam’s reservoir will have collected about 18 billion cubic meters, and its destruction will lead to a major disaster, according to experts.

Ethiopia announced in early June that it would not be able to raise the middle passage of the Renaissance Dam to a height of 595 meters, and that it would be raised to only 573 meters, which means that it would not pump an additional 13 billion cubic meters into the dam's reservoir, and therefore the second filling would be partial.

Experts considered that this represents Ethiopia’s retreat from the full filling due to Egyptian and Sudanese pressures, while others see it as just a step from Addis Ababa to absorb these pressures and implement what it deems later, and this may have originally resulted from technical difficulties that prevented the implementation of the ramp according to the previous decision. .

With the tripartite negotiations on the dam stagnant, Egypt informed the UN Security Council of its objection to Ethiopia's intention to proceed with the second filling without an agreement, in an effort to intensify pressure on Addis Ababa during this period and to internationalize the crisis.

Despite the Egyptian-Sudanese efforts to intensify political pressures on Addis Ababa, the latest of which was the meeting of Arab foreign ministers, which rejected in a statement any action or measure that affects Egypt and Sudan’s water rights, Ethiopia insisted that the second filling is not negotiable and will take place on time, while Egypt confirmed that All options remain on the table regarding the crisis.

What do the analysts say?

Staff

Editors: Zuhair Hamdani, Muhammad Al-Ali

Reporters: Khalil Mabrouk, Hassan Fadl

Designs and Infographics: Media