José Manuel Caballero Bonald was shipwrecked twice.

A seafaring legend warns that immortality is achieved in the third.

He preferred not to confirm it, although he tempted the sea many times.

Literature, flamenco and the sea were the three sides of his biography, so wide, so rich in adventure, closed today, at 94 years of age.

The penultimate witness of the Generation of Poets of 50, Caballero Bonald established himself over time as a citizen of insurrectionary vocation, civic commitment and political avatar. From his first years of university, in Seville, where he studied Philosophy and Literature, he assumed a political commitment from which he maintained very active links with the Communist Party (without reaching membership) and that before Franco's death ended in his secondment to the Democratic Board of Dionisio Ridruejo. Hence the incessant alert to the present and the need to find accommodation in the transgressions of the language to say the grievances in another way in their own way. José Manuel Caballero Bonald was the penultimate member that remained of the founding team of the Generation of 50, along with Francisco Brines.(Contemporary poets such as Julia Uceda, Antonio Gamoneda or María Victoria Atencia also keep the pulse). The last two decades in the life of the author of Descrédito del Hero have something unusual due to the huge work that has been released since he was over 70 years old, as if revived by old age. The seed of that last stretch of powerful writing was an insurgent book:

Offenders Handbook

(2005). And from there,

The night has no walls

(2009),

Entreguerras

(2012) autobiography in verse and

Unlearning

(2015).

He stood out in 1952 with

Las alucinaciones

(Adonais Award). He belonged to a unique family settled in Jerez, with a Cuban father and a mother of descent in the French aristocracy. His childhood had three essential discoveries to become who he wanted to be: literature, flamenco and the sea. To which he added the Coto de Doñana as a mythical territory that permeated a good part of his work. He studied Philosophy and Letters in Seville (between 1949 and 1952) and Nautical and Astronomy in Cádiz. After spending a few years in Madrid, already married to the Mallorcan Pepa Ramis, in 1960 he went to Colombia hired as a professor of Comparative Literature at the National University in Bogotá. His first child was born there and he wrote the first novel,

Two days in September.

(1962), with which he won the Short Library Prize.

He will be followed, back in Spain, by

Ágata, ojos de gato

(1974),

All night they heard birds pass by

(1981),

En la casa del padre

(1988) and

Campo de Agramante

(1992).

Between Spain and America, a different way of writing, reading, and interlocking with the language is developing.

And, at the same time, it broadens the critical consciousness of which he has made his own life and work.

The poet signing one of his books.

The 50s was a mainly poetic generation, storytellers and playwrights were on another path for which Carme Riera found the most accurate of the slogans in an essay on the Catalan branch of the generation: Supporters of happiness. Somehow, beyond the beating of those who were born before the Civil War and suffered its consequences, this was a playful and drinking group, night owl and festive, complicit and unequal, which established new poetic codes in Spain. Caballero Bonald was one of the expedition leaders of that adventure along with José Ángel Valente, Claudio Rodríguez, Gil de Biedma, José Agustín Goytisolo, Ángel González, Francisco Brines and Gabriel Ferrater, among others. And he enjoyed them, the shared time, the long nights as far as the light peeks out. The friendship was firm and the poetic ties scarce.Caballero Bonald was always aware that the best way to make a path in writing was to take the path alone. And in that certainty it was applied to the end. He is the strangest of the 50's poets. The one with non-transferable origins and models. The most refractory to group communion. Take solitaire shots in unmarked waters. It has the fountain on the Baroque side, but previously also in the pre-Renaissance fishing grounds, with Juan de Mena and thebut earlier also in the pre-Renaissance fishing grounds, with Juan de Mena and thebut earlier also in the pre-Renaissance fishing grounds, with Juan de Mena and the

Labyrinth of fortune

as a road map.

In the penultimate of his published books of poems,

Entreguerras

(2012), he drew these verses: "I write once again the great unanswerable question: is that which is guessed beyond the last limit still life?".

He was then 86 years old and maintained an astonishing demand in writing, made of a sharp lucidity that was not in the habit of lowering his guard.

This is the case with the last of his published books,

Examination of Wits

, a dazzling biography of affections and disaffections through some creators with whom he met throughout his century of life. What was published in 2017, at the age of 91, and from then on he chose to stay a little out of everything, between his house in Madrid and that of Sanlúcar de Barrameda, warned by the world by reading newspapers and long conversations with some friends.

Caballero Bonald is an expressive poet surrounded by silences.

He did not accept old age as an ambush or age as an escape.

Lucidity was his best shield.

He kept upset with the present and his writing also comes from there.

He assumed the poetic fact as a condition to endure disenchantment, the limits of things and of men.

And with that anticipated suspicion he began to write his last book of poems,

Unlearning

, on the verge of 80 years.

Poems arranged in prose that are an even more extreme expedition than the one undertaken in two of his main books:

Descrédito del hero

(1977) and

Labyrinth of fortune

(1984).

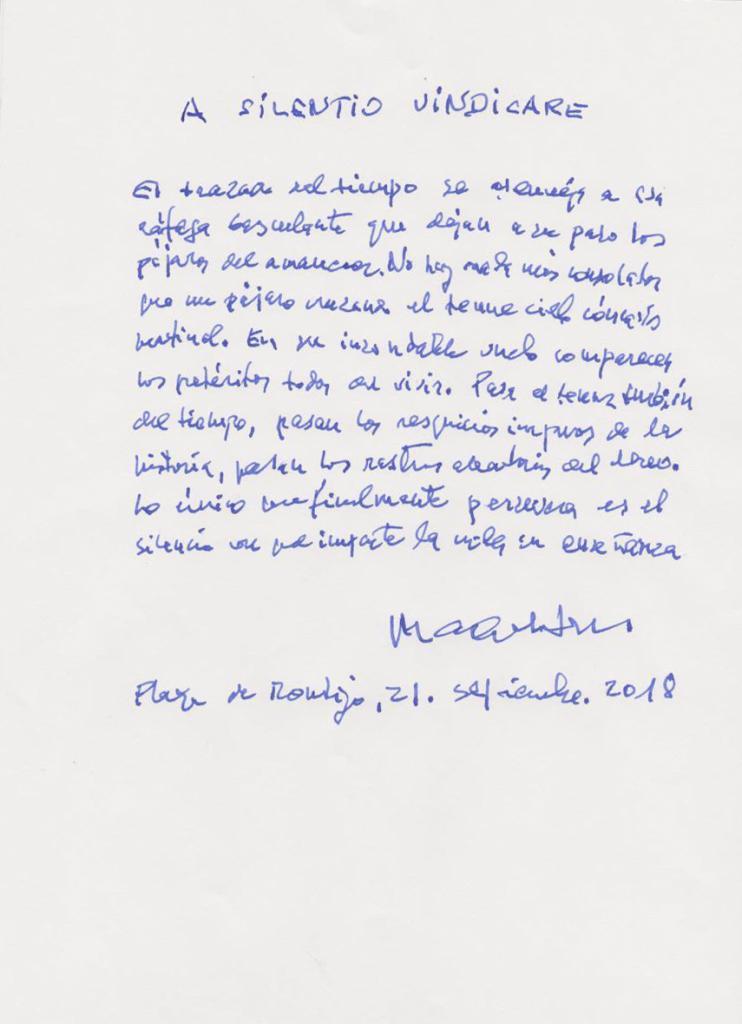

Handwritten poem by Caballero Bonald, dated 2018.

Caballero Bonald's poems are never argumentative. They do not come to tell anything, but to express the untold, what still remains to be said, what happens in the powerful regions of mind, stupor, rejection, insubordinate discomfort, amazement, love. They emerge from a conception of poetry that does not accept the fanaticism of the real. As Luis Antonio de Villena maintains, it reaches its natural breath, its deep flow, through the distortion of the discourse.

The night and the sea are two of its favorite symbols.

But also the incautious unevenness that goes from life to life, enunciated from the considerations of the one who transfers the experience to language and totality.

That is what makes his poetry manifest an imaginary full of vigor.

Also his intense narrative work and his memory adventure, gathered in a single volume with the title of La novela de la memoria.

His is a vigor of lyrical thought and hallucination, the reverse of normality, that which makes the poem an unprecedented practice and a fugue, an unpredictable transit that annuls the surrounding banality and renounces supposedly moral solutions.

But Caballero Bonald also does not act like a moralist, but rather walks closer to the translator of perplexities.

That is, among many other things, what makes it present, modern, close.

The last stage of his poetic work is made up of books of insubordination and memory. Of unusual fervor. And he shows a voluntary contempt for despicable customs, but at the same time abundant in the roots of the best poetry. That which "arouses itself, propagates itself, rediscovers itself", to put it with Pere Gimferrer. The poet's relationship with the language is conflictive and he does not shy away from the challenge. In this sense, Caballero Bonald's poetry is a necessary counter-order to the narrow realistic encirclement, and at the same time a fabulous demand, of tone and singular, of revealing emotion, not only as a stimulus, but as an attitude and redefinition of life, of what real. And that overwhelms us with authenticity. The poet does not reflect, he recreates. Show, show, teach. Never trace. In

Diary of Argonida

He says that "evoking what has been lived is equivalent to inventing it."

His writing is an invitation to think differently.

To feel without fear the dynamite of emotions, of indignations.

He owes much of his expressive power to flamenco.

And the readers and lovers of that expression, a memorable book:

Luces y sombra del flamenco

(1975), as well as the Archivo del cante flamenco, a record work published in 1968 by the Vergara label.

The cante their atavistic voices were, for the author of

Two days of September

, like a fire of life that can only be reviewed with the anxiety with which the cracking of volts is heard in a high-power transformer.

José Manuel Caballero Bonald, was the shaman who did not lose the beautiful ease of looking deeper into things and everything that encrypts a man in his costume of masks.

Weaving and unweaving its identity.

His demons.

His ravings.

Your certainties.

His passions.

His disaffections.

Its consummate forest silence.

Its massive lightness.

To live is to go from one space to another doing everything possible not to hit each other, as Georges Perec guessed.

And Caballero Bonald knew it.

And Caballero Bonald explored it.

And with that anticipated suspicion he overwhelmed us with authenticity.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more

See links of interest

Holidays 2021

Home THE WORLD TODAY

Leeds United - Tottenham Hotspur

Alaves - Levante

Stage 1, live: Torino - Torino (CRI)

Spezia - Napoli

Barcelona - Atlético de Madrid