I do not know.

In retrospect, the very first words of Maxim Grigoriev's

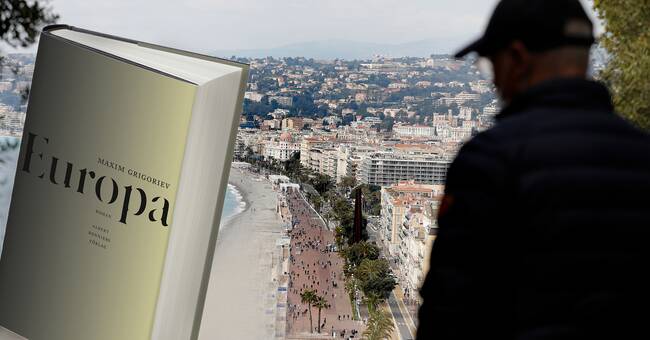

Europe

provide

an answer to the question of what kind of story this is.

The simple sentence "I do not know" is repeated 99 times in the novel and it says that the narrator does not know what he wants to say, he has no message, no clear or even hidden intention, here there is no plot, no chronology and no hero.

His name is Nikita

and he is standing in a musty-smelling apartment in Nice, looking out over the Mediterranean.

It's autumn, he's never been there before, he's just inherited the two-room apartment from an old friend, Nina.

She found him sleeping on a bench in Paris where he was on a school trip but missed the trip home to Moscow.

He was 14 then, remained in Paris and has never been back to Moscow since, other than in the years of increasingly shimmering nightmares.

Now he is an overweight 40-year-old who lets his eyes wander through the empty apartment.

Anyone who wants a novel where something happens, a story with a beginning and an end about war and love, crime and punishment, will not find himself in

Europe

.

But anyone who reads to practice their sensitivity, get close to people and think about what a life really is, will want to stay long in this book.

Maxim Grigoriev was

born in Russia and grew up in Sweden.

He writes in Swedish but places his novel in the middle of the world.

In Paris and on the Riviera, Russian exiles have lived for over a hundred years, Nikita is just one in an aging crowd of people living with their memories and their homesickness.

Their days flow together in the cafés' outdoor cafes, where they read classics and write exile literature, complaining about history and the present.

They are strangers, but not because they have changed country: they have changed country because they are strangers, as it says somewhere in the novel.

The further I get into Nikita's thoughts and memories, and his memories of Nina's thoughts and memories, the clearer it becomes that the novel is about everyone who in some sense is strangers in reality because it holds so much more than can be perceived, and because a human being is so much more than an immigrant.

Grigoriev's novel opens the

eyes to a Europe that is far from being a bustling diversity where everyone meets everyone instead is a world full of closed enclaves where people live without contact with others, those who speak and write other languages.

Quotes in Russian stop reading, those who read electronically can copy and cut into a translation program, but it gives more to instead let go and let themselves be carried away by the rich stream of words.

It is the words that give life meaning, but you do not have to understand everything, it is enough to open the window like Nikita and let in the strange.

Nikita is in many ways a melancholy figure, almost reluctant in his encounters with other people, a listener and observer, like a reader, but with a rare stylistic ability and linguistic sensitivity that makes exile a pleasure.